PatentNext Takeaway: Companies have increased

access to artificial intelligence (AI) tools, such as ChatGPT and

Github Copilot, which promise to improve the efficiency and work

product output of employees. However, the adoption of such AI tools

is not without risks, including the risk of loss of intellectual

property (IP) rights. Accordingly, companies should proceed with

caution by considering developing an AI policy to help eliminate or

mitigate such risks. An AI policy can look similar to, and in many

cases be a supplement to, a company’s open-source software

policy.

****

A company onboarding artificial intelligence (AI) tools can

experience increased efficiencies of work product output by

employees, including the acceleration of software and source code

development.

However, there are several intellectual property (IP) risks that

should be considered when onboarding such AI tools. This article

explores certain IP-related risks of adopting and using AI tools

and also provides AI policy considerations and example strategies

for how to eliminate or mitigate such risks.

Potential Risks

Risk 1: Possible Loss of Patent or Trade Secret

Rights

Under U.S. Patent law, public disclosure of inventive

information can destroy potential patent rights. That is, a claimed

invention can be found invalid if it is made “available to the

public” (e.g., a public disclosure) more than 1 year before

the effective filing date of the claimed invention. See 35

U.S.C. § 102.

Similarly, a public disclosure can eliminate a trade secret. To

be legally considered a trade secret in the United States, a

company must make a reasonable effort to conceal the information

from the public.

With respect to AI tools, a user’s input into a generative

AI tool, such as ChatGPT or Github Copilot, may be considered a

“public disclosure” that could destroy patent and/or

trade secret rights. For example, OpenAI (the creator of ChatGPT)

provides in its “Terms of Use” that a user’s input

may be reviewed or used by OpenAI “to help develop and improve

[their] Services.”

Thus, the input of sensitive data (e.g., patent claims, trade

secret data) in ChatGPT’s prompt could be considered to be a

“public disclosure” that, if significant, could result in

waiving trade secret protection and/or precluding patent

protection.

Risk 2: Unintended Data Sharing

Data provided to an AI tool can be used in unintended ways. For

example, a company’s provision of sensitive information (e.g.,

patent claims, trade secret information, source code, or the like)

to a third party (e.g., OpenAI) via an AI tool (e.g., ChatGPT)

could result in such sensitive information being used to train

and/or update the AI model. Furthermore, in an unlikely but

possible scenario, a newly trained model (e.g., as trained with a

company’s data) may then output sensitive data (e.g.,

confidential information) to third parties (e.g., competitors).

Thus, through the mere use of an AI tool, a company could

unintentionally provide sensitive information to others, including

its competitors.

Risk 3: Potential Issues with Copyright Authorship /

Patent Inventorship

Ownership of a copyrighted work (e.g., source code) begins with

authorship, where an author is a person who fixed the work in a

tangible medium of expression. See 17 U.S.C. §

102(a). For example, for software, this can include simply saving

the source code in computer memory. Under current U.S. laws, an AI

system or tool cannot be an “author”; only a human can

be. See, e.g.,

PatentNext: U.S. Copyright Office Partially Allows Registration

of Work having AI-generated Images (“Zarya of the

Dawn”).

Similarly, patent rights begin with inventorship, where an

inventor is a person who conceives of at least one element of a

claim element of a patent. Under current U.S. laws, an AI system or

tool cannot be an “inventor”; only a human can be.

See

PatentNext: Can an Artificial Intelligence (AI) be an

Inventor?

Thus, if an AI system or tool cannot be an “author” or

an “inventor,” as those terms are interpreted according

to U.S. law, then what happens when a “generative” AI

model (e.g., ChatGPT) produces new content, e.g., text, images, or

inventive ideas, in the form of an answer or other output (e.g., a

picture) it provides in response to a user’s input?

The question underscores a potential risk to valuable copyrights

and/or patent rights by the use of an AI system or tool to generate

new seemingly copyrighted works (e.g., source code) and/or conceive

of seemingly patentable inventions. Currently, the U.S. copyright

office requires authors to disclose whether AI was used in creating

a given work; the copyright office will not allow registration or

protection of AI-generated works. See, e.g., PatentNext: How U.S. Copyright Law on

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Authorship Has Gone the Way of the

Monkey.

The U.S. Patent Office has yet to address this issue with

respect to inventorship; thus, a patent created with the assistance

of an AI tool could be called into question, including possibly

rendering an AI-generated patent claim invalid, at least according

to one school of thought. See PatentNext: Do you have to list an Artificial

Intelligence (AI) system as an inventor or joint inventor on a

Patent Application?

Risk 4: Inaccurate and Faulty output (AI

“hallucinations”)

While the output of a generative AI Tool (e.g., ChatGPT or

Github Copilot) can be impressive and seem “human” or

almost human, it is important to remember that a generative AI tool

does not “understand” or otherwise comprehend a question

or dialogue in the same sense a human does.

Rather, a generative AI tool (e.g., ChatGPT or Github Copilo) is

limited in how it has been trained and seeks to generate an output

with a selection and arrangement of words and phrases with the

highest probability mathematical output, regardless of any true

understanding.

This can lead to an AI “hallucination” (i.e., faulty

output), which is a factual mistake in an AI tool’s generated

text that can seem semantically or syntactically plausible but is,

in fact, incorrect or nonsensical. In short, a user can’t trust

what the machine is explaining or outputting. As Yann LeCun, a

well-known pioneer in AI, once observed regarding AI hallucinations:

“[l]arge language models [e.g., such as ChatGPT] have no idea

of the underlying reality that language describes” and can

“generate text that sounds fine, grammatically, semantically,

but they don’t really have some sort of objective other than

just satisfying statistical consistency with the prompt.”

One example of an AI hallucination with a

real-world impact involved an attorney, Steven Schwartz (licensed

in New York). Mr. Schwartz created a legal brief for a case (Mata v. Avianca) in a Federal

District Court (S.D.N.Y.) that included fake judicial opinions and

legal citations, all generated by ChatGPT. The court could not find

the judicial opinions cited in the legal brief and asked Mr.

Schwartz to provide them. But he could not do so because such

opinions did not exist. ChatGPT simply made them up via AI

hallucinations. Later, at a hearing regarding the matter, Mr.

Schwartz told the Judge (Judge Castel): “I did not comprehend

that ChatGPT could fabricate cases.” Judge Castel sanctioned

Mr. Schwartz $5,000. Judge Castel also noted that there was nothing

“inherently improper” about using artificial intelligence

for assisting in legal work, but lawyers have a duty to ensure

their filings were accurate. As a result, judges and courts have

since issued orders regarding the use of AI tools, where, for

example, if an AI tool was used to prepare a legal filing, then (1)

such use must be disclosed; (2) an attorney must certify that each

and every legal citation has been verified and is accurate.

Risk 5: Bias

A generative AI tool can be limited by its reliance on the human

operators (and their potential and respective biases) that trained

the AI tool in the first place. That is, during a supervised

learning phase of training, an AI tool may not have learned an

ideal answer because the specific people selected to train the tool

chose specific responses based on what they thought or knew was

“right,” at least at the time, but where such responses

may have been incorrect, or at least not ideal, at the time of

training. The risk is that such training can lead to biased output,

e.g., not reflective of target user or customer needs and/or

sensitivities.

Still further, a different kind of bias can come from

“input bias,” in which a generative AI tool can respond

with inconsistent answers based on minor changes to a user’s

question. This can include where minor changes to a user’s

input can, on the one hand, cause a generative AI tool to claim not

to know an answer in one instance or, on the other hand, answer

correctly in a different instance. This can lead to

inconsistent/non-reliable output, e.g., where one user receives one

answer, but another user receives a different answer based on

similar but different input.

AI Policy Considerations and Mitigation Strategies

The below discussion provides AI policy considerations and

example strategies for how to possibly eliminate or mitigate the

potential risks described above.

Avoid public disclosures implicit in AI

Tools

One possible solution for reducing the risk of public disclosure

is to obtain a private instance of a generative AI

tool (e.g., ChatGPT). A private instance is a version of the AI

tool that could be securely installed on a private

network inside a company.

Ideally, the private instance would receive and respond to any

queries from employees. Importantly, such queries would not be sent

publicly over the Internet or to a third party. This could avoid

potential 35 U.S.C. § 102 public disclosures and/or trade

secret-destroying disclosures that could occur through the use of

standard or freely available tools, such as ChatGPT, available to

individual users.

Negotiate or set favorable terms or features that avoid

improper data misuse

Typically, acquiring a private instance of an AI tool (e.g.,

such as ChatGPT) includes negotiating terms and/or setting up

features of the AI tool during installation. Favorable terms and/or

features can avoid improper data misuse by others and further

prevent unwanted public disclosure.

For example, a company can reduce risk by negotiating favorable

terms with AI tool providers and/or requiring the setting of the

following features with respect to a given AI tool:

- The company should require two-way confidentiality, in which

data provided to and sent from the AI tool is secured and treated

as confidential by both parties, i.e., the company using the AI

tool and the AI tool provider. - The company should opt out of any data training scheme that

allows the AI tool provider to use the company’s provided data

as training data to update the AI tool. - The company should require a zero-data retention such that any

input provided to the AI tool provider is not stored by the AI tool

provider. - The company should require an indemnity from the use of the AI

tool. For example, the AI tool provider should agree to indemnify

the user and/or the company against any future infringement claims,

e.g., copyright infringement. For example, Microsoft has agreed to

indemnify commercial users of its GitHub

Copilot tool for generating source code from AI.

Formal AI Policy

The company can prepare a formal AI Policy to be followed by

employees. The AI Policy can be similar to, or in addition to

(e.g., a supplement to), the company’s Open-Source Software

policy. For example, the AI Policy can involve:

- Creating a whitelist of allowed AI tools.

- Creating a blacklist of disallowed AI tools.

- Assigning a Single Point of Contact (SPOC) person or team to

facilitate questions regarding AI usage. - Avoiding or minimizing copyright infringement:

The company can check that the output of a generative AI tool is

sufficiently different from (not substantially similar to) data

used to train the AI tool’s underlying model (e.g., to reduce

potential accusations of copyright infringement of substantially

similar works). - Mitigating Inventorship/Authorship disputes:

The company can require authors and/or inventors to keep an

input/output log as evidence to show human

contributions/conception to copyrightable works and/or patent claim

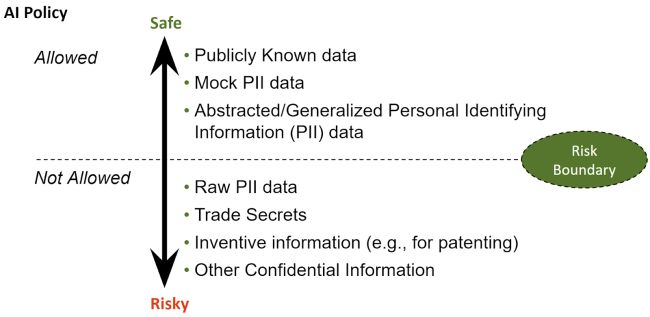

elements. - Categorizing/ranking Data types based on risk:

The AI Policy can categorize or rank which data inputs and/or

outputs to allow. This can be based on the type of data and the

company’s risk tolerance (see below example charts illustrating

this).

Categorizing and/or ranking of data types based on a

company’s risk tolerance can involve defining data types and a

risk boundary. Then, the company can determine whether data types

are considered “safe” or “risky” based on the

risk boundary, which can be the amount of risk the company is

willing to accept for the benefit of using of a given AI tool.

The chart below provides an example framework for AI inputs. The

below example framework illustrates data types as input into a

generative AI tool such as ChatGPT across a given risk boundary

defining “allowed” and “not allowed” use

cases:

As shown above, data that is publicly known and/or

nonconfidential data is allowed as input into a given AI tool

(e.g., ChatGPT). On the other hand, confidential information, such

as PII, trade secret data, and/or inventive information for

patenting, is not.

Similarly, the chart below provides an example framework for AI

outputs. The below example framework illustrates data types as

output by a generative AI tool such as ChatGPT across a given risk

boundary defining “allowed for public use” and “not

allowed for public use” use cases:

As shown above, data that is curated, checked, or that is

generated specifically for public consumption is allowed as output

from a given AI tool (e.g., ChatGPT). On the other hand,

confidential data output based on confidential information is not

allowed.

Eliminate or reduce low-quality model output and model

bias

When training an AI model, a company should consider the risk of

model bias (as discussed above). One related risk that should be

considered is the programmer’s age-old adage of “garbage

in, garbage out.” This effectively means that inputting

garbage data (e.g., erroneous or non-related data) will result in

garbage output (e.g., erroneous or non-related output). In the case

of AI models, inputting low-quality training data will lead to

low-quality model output, which should be avoided. Instead, a

company should use curated data that is property correlated in

order to make the AI model’s output high-quality and

accurate.

Also, a company should consider using only licensed or free data

for training an AI model. Using such licensed or free data can

avoid accusations of copyright infringement, where the company

could be accused of improperly using licensed/copyright data to

train an AI model.

Finally, an AI model should be trained in a manner to eliminate

model bias. This can include using data with sufficient

variability/breadth to avoid model bias with respect to end-user

needs and/or sensitivities. Model bias can be further reduced by

implementing or considering ethical considerations and concerns,

such as those put forward by the White House’s Blue Blueprint

for an AI Bill of Rights, which seeks to acknowledge and address

potential inherent ethical and bias-based risks of AI systems. See

PatentNext: Ethical Considerations of

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the White House’s Blueprint

for an AI Bill of Rights.

More recently, President Biden issued an Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial

Intelligence practices. One of the enumerated requirements of

the Executive Order requires AI developers to address algorithmic

discrimination “through training, technical assistance, and

coordination between the Department of Justice and Federal civil

rights offices on best practices for investigating and prosecuting

civil rights violations related to AI.” The goal of the

requirement seeks to eliminate bias because, according to the

Executive Order, “[i]rresponsible uses of AI can lead to and

deepen discrimination, bias, and other abuses in justice,

healthcare, and housing.”

Another enumerated requirement of the Executive Order states

that “developers of the most powerful AI systems share their

safety test results and other critical information with the U.S.

government.” It can be assumed that “most powerful AI

systems” refer to AI systems such as ChatGPT, and the

“developers” are those companies that develop such AI

systems, e.g., OpenAI. Thus, most companies that simply use AI

tools (and that do not develop them) will not be affected by this

requirement of the Executive Order.

Conclusion

An AI tool, if adopted by a company or other organization,

should be considered in view of its potential impacts on IP-related

rights. Using an AI tool without an AI Policy to assist the

management of important IP considerations could result in the loss

of IP-related rights for the company. Therefore, a company should

consider developing an AI Policy that eliminates, or at least

mitigates, the risk of IP loss from AI tool adoption and/or

uncontrolled AI tool use by employees.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.