Taiwanese artist Su Hui-Yu describes his first encounter with the underground cinema and theatre in Taipei in the 1990s as accidental. “One day I was walking outside the campus, and a flyer literally flew in my face,” he says. “It was advertising a theatre show, and that’s where I first read the word queer. What is ‘queer’, I wondered? It sounded so attractive!”

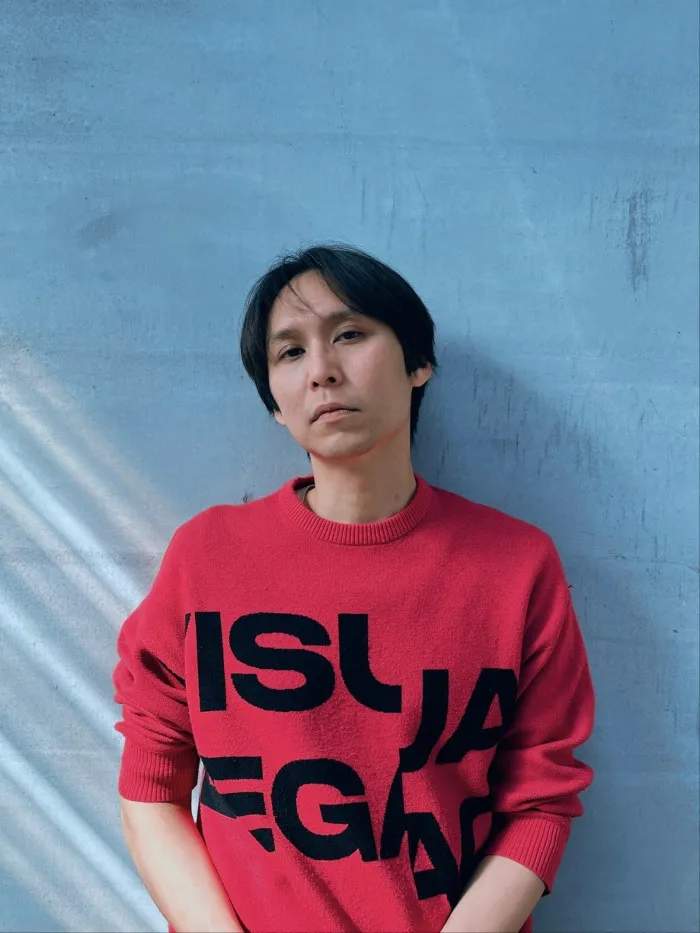

A lean man in his forties with pensive eyes, round glasses and a bowl cut, Su has been testing the limits of the socially acceptable and the politically relevant throughout his career, his work probing and transgressing boundaries. He sees his own interest in transgression as an inevitable result of the collective sexual repression that Taiwanese people experienced in the 1980s under martial law. With his work Su wants to give expression to those shared memories of forbidden and unspoken desire.

The son of a painter, Su was encouraged to start a career in the arts early on: “I think I have the gift of painting, and I always thought about art as a job,” he says over Zoom from his studio in Taipei. After graduating from Taipei National University of the Arts in 2003, he started experimenting with performance art, before dedicating himself to video art and film.

The Taiwanese art scene celebrated him with his 2023 solo show at MoCA Taipei: “I’m super-grateful for my work to be neatly exhibited in museums, galleries and art fairs,” he says. “But I’ve a kind of nostalgia for the grungy Taipei underground world of my youth, that DIY ethos beyond institutionalisation and marketisation. All I do with my work is try to revive that spirit.” He pauses and laughs. “Oh no, I sound like an old man!”

His video “The Walker” is a surreal tableau vivant. The camera slowly zooms out to reveal a group of extravagantly dressed characters in a crowded room, making small, repetitive movements. This was inspired by the performances of the experimental theatre group Taiwan Walker. “It’s all from my memories,” he says. “I looked for a house that reminded me of Nineties Taipei, and I mixed the original text from the theatre script with some contemporary subtexts.

Despite having some nudity and raunchy sex talk, “The Walker” will be shown at Art SG art fair without any limitations or cuts imposed by the infamous Singaporean rating system. “I guess an art fair is less controlled compared to an institutional space,” he says.

Su’s work has not always translated well from the liberal Taiwanese art scene to buttoned-up Singapore. In 2018, his film “Super Taboo” — presenting a series of surreal erotic scenes inspired by vintage Taiwanese pornography — didn’t get a rating and Singapore’s Asian Film Archive couldn’t screen it.

These episodes are not new for the artist, who is constantly forced to edit his work depending on the context where it is shown. His immersive projection “The Space Warriors and the Digigrave” received the VH Award for new-media artists, but was in part censored for the prize presentation in Korea. “I guess [they] didn’t want to see breasts at an official ceremony,” he sighs.

The artist works between transgression and social justice, an interesting but slippery space: “Recently my work has received quite harsh criticism, in the light of Taiwan’s #MeToo movement,” says Su, because some scenes in his videos show women being subjected to violence. “This got me to think deeper about where to draw boundaries. As men, we held privilege for centuries, and we need to take responsibility.”

A big part of Su’s work has empowered women as protagonists, albeit often galvanised by violence. An example is “The Women’s Revenge”, a Tarantino-like video piece reinterpreting the revenge/exploitation genre movies from the 1980s. With the aid of AI, he even lent his own face to one of the women in the gang.

His fascination with B-movies dates back to when he was a child. In his art practice he recovers the original screenplays and shoots parts that the directors couldn’t at the time because they were considered too extreme. In the process, he has involved members of Taipei’s queer community and non-professional actors from different activist groups. One of the most powerful of his reshootings is “The Glamorous Boys of Tang”, where Su deploys impeccable aesthetics to treat gut-wrenching scenes of sex and violence.

His work is not all transgression and extremes. His most recent projects explore collective memories of oppression and liberation in Taiwanese history, including his second piece at Art SG, which is both existentialist and political. Titled “L’être et le néant” (“Being and Nothingness”) after Jean-Paul Sartre’s book, it is inspired by a surreal picture by photoreporter Chang Chao-Tang depicting a headless human shadow. “That image for me evoked the shadow of martial law in Taiwan in 1962,” says Su. “It was a time called the White Terror, where a number of executions were carried out by the government.”

The artist elaborated on the photograph by creating a static video reimagining the making of the picture. In the video there is a man in front of a car’s headlights, projecting a headless shadow on a cloth behind him. Only clouds of smoke move. “I spoke with Chao-Tang and he said he didn’t mean to reference the White Terror,” says Su. “I guess he was subconsciously capturing a collective mood.”

Politics and history are at the forefront of the artist’s latest production: “Looking back at my practice, in the beginning, I was fascinated by the body, sex, the self and gender. But slowly I started to realise that the body is political, and you can’t avoid thinking about it in a wider context.”

In “The Space Warriors and the Digigrave”, Su explores AI and sci-fi. The immersive video installation plays on the errors and glitches that AI produces when it’s given too much information: “In the end, feeding prompts to an AI is like making a soup. You can’t really predict the end result.”

Concerns with the mindless use of technology are also at the heart of his “Future Shock”, part of Art SG’s screening programme. For this feature film, he draws from the prophecies of futurologist Alvin Toffler who, back in 1970, talked about the collective psychological distress from the hyper-accelerated rate of societal change in industrial societies.

The artist is well aware of the danger of uncontrolled technological development and its effects on Asian societies, a concern alongside the fragile political situation of Taiwan, constantly threatened by China. “I’m not saying I am not worried,” he says. “But I also see things as an artist. I look at it as the human comedy. And that’s when I go: Fuck it! I’ll just put everything into my work. It’s chaos, and I like it!”

suhuiyu.com. Singapore Art Week runs January 19-28

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen