“What I do involves a lot of dirt,” says Thomas Schütte as he lights another cigarette. “Dirt and dust and material. Other people might make video art, but I can’t sit down and work like that. I like to handle material. Working with clay is like therapy. And if I get bored with that, I turn to something else.”

The German artist, who turned 70 last year, is perched above Venice, in the twisting tower of the Punta della Dogana. One of the two historical buildings in the city converted into art galleries in the 2000s by luxury magnate François Pinault, the Dogana is a former customs house, and occupies the triangular tip of land where the Grand Canal and the Giudecca Canal converge. The view from up here is sensational on a sunny spring day but Schütte likes this spot because it’s outdoors and he can smoke. He keeps a tiny round tin in the pocket of his buff linen jacket for the cigarette butts.

Below, in the Dogana’s capacious rooms, is a new exhibition of his work from 1977 to now, though it is no retrospective. Instead it follows certain lines of connection and repeated motifs through his five-decade career — it is called Genealogies — and includes the monumentally scaled sculptures that Schütte-watchers might expect as well as a number of intimate watercolours that have never been shown before. It’s a tonal yin and yang — from very loud to quiet as a whisper.

Schütte is best known for the first — contorted fighters with froggy faces; busts of big-nosed, sunken-cheeked dignitaries on heroic plinths; elongated, collapsing Michelin men in aluminium (three are permanently installed outside Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art). Lumpy, large and sometimes lunging, Schütte’s men are out-sized, messed-up versions of their classical statuary antecedents; critiques of assumed but delusional superiority. Their faces are imaginary, but somehow still recognisable — the sort that fill our news feeds, doers of both right and wrong.

The watercolours, though, are altogether different: brilliantly coloured and virtuosic sketches of snakes and flowers; faces, ladders, letters, even — the epitome of despair — a single lost sock. This is Schütte’s diary: swiftly made, deeply personal. “I’m not a man of words,” he says. His tales of the fragile human condition are visually told.

Schütte is one of those artists who is both “international” and not exactly a household name. He won a Golden Lion — one of the art world’s top accolades — at the Venice Art Biennale in 2005. MoMA staged a big retrospective in New York last autumn. Positively reviewed, it didn’t make the must-see lists. It is perhaps because his work is slippery to understand as it totters from elliptical to bombastic. Schütte certainly doesn’t push a brand. His range is huge — bronzes, works in glass, mangled female nudes, laugh-out-loud sculptures (a Pringle balanced on a matchbox!), and architectural models. There’s even a series of gravures of plants on show in Venice. They are called “Fleurs pour M Duchamp”, because nature is full of the “ready-mades” with which Duchamp single-handedly changed the story of western art and Schütte is paying his respects.

But, as this exhibition aims to show, he does cleave to a number of themes: our delusional selves, anxiety, the corruption of the powerful, the impossibility of defining good and bad, the inevitability of death. “The work is about all parts of human identity, but not in a blatant way,” says Camille Morineau, co-curator of the Venice exhibition. “It’s open and complex. What some people see as a comical take on human failure, others see as terribly sad.”

Schütte studied at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf through most of the 1970s, where peers included the sculptor Katharina Fritsch and the photographer Thomas Struth. “People talk about the ’70s in Germany as the grey decade,” he says. “But they were pretty wild. All the films, the music . . .” One teacher was Gerhard Richter — the artist famed for blurry realist paintings and multi-million-dollar auction results — who impressed upon his students that they should find their own way and build a wide repertoire of work.

Schütte did both and, like Richter, he embraces and challenges centuries of art history in his work. Look at his women, lying on their cold bronze slabs, taking their cues from Michelangelo to Maillol, the paintings of Ingres, and the smashed-up nudes of cubism. They are both reflections on centuries of objectification, and intense studies in form. “Most of the time, I have the feeling that it’s not me who has made them,” he says. “This is a story I did not write.”

On the terrace of the tower, Schütte talks about his day. “I have mornings now,” he says. “I used to sleep until 11 or 12, but then I stopped drinking. It had become dangerous.” This was in 2022. He checked into a psychiatric clinic near Düsseldorf, and during his recovery made many of the watercolours on show here. “I walk the three minutes from my house to my studio, then . . . we go to the ceramic workshop in Cologne or the bronze foundry in Düsseldorf.” He owns neither, preferring to co-opt other people’s spaces.

In 1989, Schütte created a series of flags, taking the most political of objects — and one with a direct relationship to abstract expressionism and its implications of American cultural imperialism — and turning it into pictorial canvas. Not seen since, these flags, “DEKA Fahnen”, hang in the first room of the exhibition, filling the walls with cherries, anchors, musical notes and piles of black lemons. On one, a potato is wearing a crown.

They surround three huge bronze statues of men whipped by wind, their feet seemingly sunken into mud (“Mann im Wind I-III”, 2018). It’s a visual metaphor that Schütte has used since the early 1980s, when the only way he could make a wax figure stand up was to submerge it in ever more wax. “But often I feel like this,” he says, “really stuck, nowhere to go.”

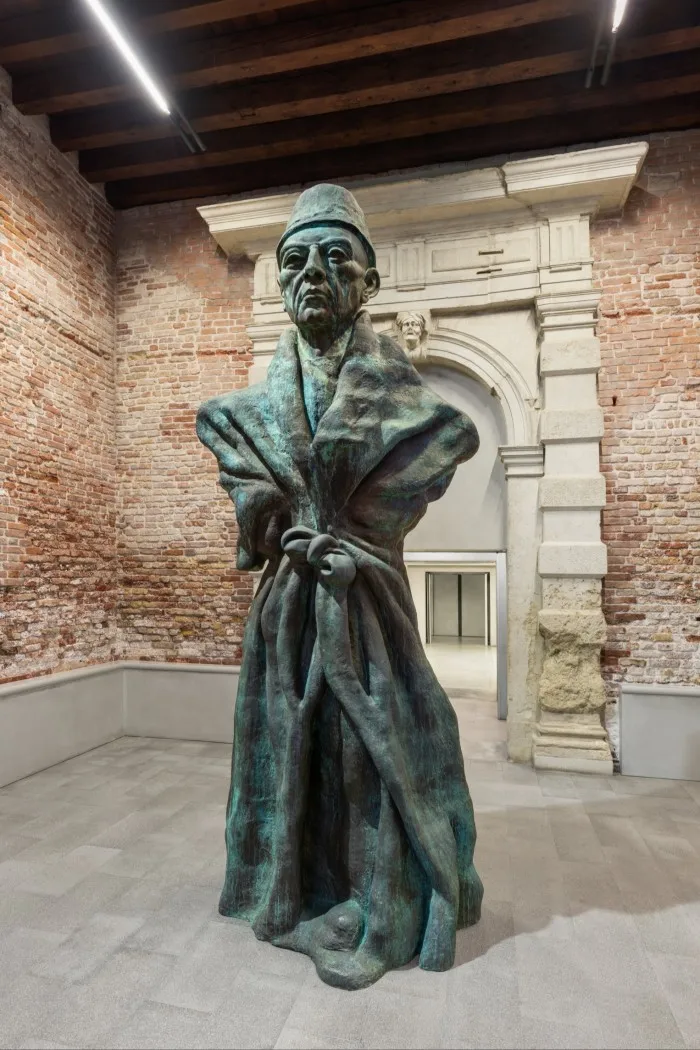

It’s a slightly disingenuous stance for such a prolific artist, whose scale of work has grown with his reputation. This has perhaps reached its conclusion with “Vater Staat” (“Father State”) — an almost 4m-high bronze that stands in the Dogana’s original entrance, an impotent colossus wrapped in a dressing gown. “He is like a big puppet, a man with no substance,” says Jean-Marie Gallais, who co-curated the exhibition with Morineau. The gown is familiar, from Rodin’s famous likeness of Balzac, where it conferred some kind of genius. “Vater Staat”’s female counterpart, “Mutter Erde” (“Mother Earth”), stands at the Dogana’s new entrance, strong and grounded and wearing a crown — a riposte to those who see his nudes as ugly or even misogynistic.

The quiet watercolours near the end of the exhibition represent a total reversal of scale. “I went to visit him at home, and he gave me a pile of all the drawings he made in the clinic in 2022, and 30 minutes to choose 50 of them,” says Morineau. (Schütte explains that he was cooking a risotto, and that’s how long it takes.) “When we finally hung them in the Dogana, it was difficult for him to see them on display. He couldn’t walk through the room, he was just looking at the floor . . . He’s very critical of himself and that’s what makes him a good person and a good artist.” Or as Schütte himself says, “It’s OK to have tears. It’s those with no emotions who are really in trouble.”

To November 23, pinaultcollection.com