Abstract

Studies on the association between depression and self-reported endometriosis are limited, and further studies are required to investigate this association. Data were collected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database (2005–2006). Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 100 participants with self-reported endometriosis and 1295 participants without self-reported endometriosis were included, representing a total population of 64,989,430. Depression severity was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9). A survey-weighted logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the association between depression and endometriosis. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore heterogeneity. The prevalence of endometriosis was 7.17%. A significant positive association was found between the PHQ9 score and endometriosis. After adjusting for all covariates, the PHQ9 score positively correlated with endometriosis. Furthermore, compared with the participants without depression, those with moderate depression were more prone to have endometriosis both in unadjusted and fully adjusted model. However, the relationship between severe depression and endometriosis was not significant in all models (P > 0.05). Our findings highlight the influence of depression on the prevalence of self-reported endometriosis. Further studies are required to elucidate the causal relationship between depression and self-reported endometriosis.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a complex chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the appearance of endometrial tissues (glands and stroma) outside the uterus1, 2. As a common benign gynecological disorder, the incidence of endometriosis is thought to reach 10% in females of childbearing age; however, the incidence may be even higher owing to the high rate of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis3, 4. Although numerous studies have been conducted, the etiology of endometriosis remains unclear5. Clinically, endometriosis is closely associated with pelvic pain, menstrual cramps, and infertility, imposing enormous financial and social burdens on individuals, families, and society6. Further research is required to identify better options for preventing and managing endometriosis.

Depression is a common psychiatric disorder adversely affecting psychological and physical health worldwide, making it a substantial public health issue7. Clinically, depression is associated with many chronic diseases, and patients with depression are more prone to worsening disease progression than patients without depression8, 9. Studies have found a strong correlation between depression and gynecological diseases, including infertility and cancer10. Depression may also be an important risk factor for sexual dysfunction11. Given these perspectives, it is worth exploring whether depression is closely associated with the risk of endometriosis. However, no studies have explored the link between depression and the prevalence of endometriosis after adjusting for multiple covariates such as age, race, and other exposures.

This study explores the association between depression and self-reported endometriosis using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2005–2006), elucidating the role of depression in endometriosis prevalence.

Methods

Study design and participants

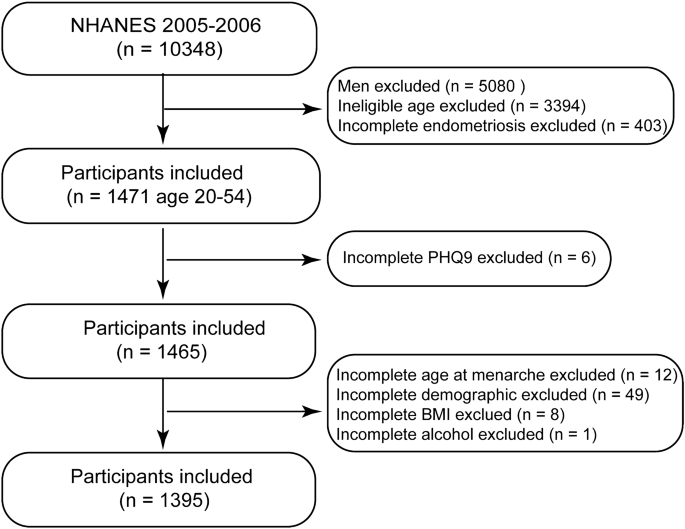

Since 1999, the NHANES database has provided a continuous and multistage probability sample for assessing health and nutritional status in the United States12. Survey participants were interviewed at home. Subsequently, physical and laboratory examinations were performed at a mobile examination center (MEC). The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board provided ethics approval (Protocol #2005-06) for all potential study protocols in the NHANES, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Therefore, no external ethical approval and informed consent were required. All analyses in this study were performed in accordance with the NHANES guidelines and regulations. After a comprehensive search and screening of the NHANES database, participants from 2005 to 2006 were included in this study. Male participants were excluded, and only females aged 20–54 years were included. Simultaneously, individuals with incomplete information on self-reported endometriosis, Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9), and covariates were excluded. The flowchart of the screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the screening process from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005–2006). BMI, body mass index.

Exposure and outcome definitions

PHQ9 is a reliable questionnaire for rating mood based on standard diagnostic criteria for depression13, 14. The PHQ9 scale consists of nine items rated from 0 to 3, with the total score ranging from 0 to 2715. The depression severity of the survey participants was evaluated using PHQ9, administered in an MEC16. The depression was defined as a total PHQ9 score ≥ 1017. For participants with depression, the degree of depression was further divided into moderate (total PHQ9 score: 10–14) and severe depression (total PHQ9 score ≥ 15)18. The grade of depression and PHQ9 score of each participant were then calculated for further analysis.

Self-reported endometriosis was diagnosed based on the “rhq360” questionnaire administered in the MEC. The structured questionnaire comprised the question, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have endometriosis?”19. Individuals who answered “yes” were categorized into the case group with self-reported endometriosis, and individuals who answered “no” were classified into the control group without self-reported endometriosis.

Potential covariates

Demographic covariates, including age, race, marital status, educational level, and poverty level, were obtained through home interviews. According to the age distribution, the participants were divided into three groups: first (20–29 years), second (30–40 years), and third (41–54 years) tertiles. Marital status was defined as married, divorced, separated, or spinster20. The participants’ educational level was recorded as less than high school, high school, or college and above21. Poverty level was evaluated based on the poverty income ratio (PIR) and classified as follows: low-income (PIR < 1.35), medium-income (1.35 ≤ PIR < 3.0), and high-income (PIR ≥ 3.0)22. Health-related covariates, including smoking status and alcohol use, were evaluated in the MEC. According to the smoking and tobacco use questionnaire, smoking status was categorized as never, former, or current, whereas alcohol consumption was classified as never, former, mild, moderate, or heavy. Age at menarche and history of pregnancy were included as disease-related covariates using “rhq” 010 and 031 questionnaires23, 24. Body mass index (BMI) was classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)25.

Statistical analysis

Due to the complex multistage sampling design of the NHANES, all data were merged and weighted using wtmec2yr under the NHANES protocol26. The baseline characteristics of the participants were first compared using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables27. For descriptive statistics, the variables were expressed as weighted means (standard error). Categorical variables were presented as numbers (weighted percentages). Next, weighted univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the correlation between depression and endometriosis. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, three models were constructed: (1) Model 1 (no covariate were adjusted), (2) Model 2 (adjusted for variables found to be significant in the univariate logistic regression analysis), and (3) Model 3 (adjusted for all covariates). Finally, the statistical P for interactions between the covariates and the PHQ9 score was calculated, and subgroup analyses were conducted to further clarify these results. The weighted logistic regression and subgroup analysis results are expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All analyses were performed using R and R studio (version 4.2.1), and P < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Population characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. After a series of screenings, 1395 participants were included from the NHANES database (2005–2006), representing a total population sample of 64,989,430. Of these, 100 (7.17%) individuals had self-reported endometriosis, whereas 1295 (92.83%) did not. Significant differences in age, race, PIR, and the PHQ9 score were found between patients with and without self-reported endometriosis (P < 0.05).

Weighted logistic regression

To explore the link between depression and self-reported endometriosis, weighted univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed. As shown in Table 2, Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, PIR, and race; and Model 3 was adjusted for all covariates. Compared with the participants without depression, the association between the PHQ9 score and endometriosis was robust and significant in Model 1 (OR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.10), Model 2 (OR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12), and Model 3 (OR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.11). The same relationship was verified between moderate depression and endometriosis through Model 1 (OR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.02–4.57), Model 2 (OR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.11–4.75), and Model 3 (OR = 2.49, 95% CI 1.09–5.69). However, the relationship between severe depression and endometriosis was not significant in any model (P > 0.05). Compared with the age group of 20–29 years, the age group of 41–54 years was found to be positively correlated with endometriosis prevalence in Model 1 (OR = 3.33, 95% CI 1.45–7.63), Model 2 (OR = 2.88, 95% CI 1.05–7.93), and Model 3 (OR = 2.91, 95% CI 1.01–8.41). With regards to race, compared with non-Hispanic White, Mexican American race was negatively correlated with endometriosis prevalence in Model 1 (OR = 0.15, 95% CI 0.05–0.47), Model 2 (OR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.05–0.65), and Model 3 (OR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.07–0.70). Regarding the PIR covariate, no significant relationship was identified between medium- or high-income and endometriosis across all models compared with low-income (P > 0.05).

Subgroup analyses

To assess the influence of potential effect modifiers on the prevalence of self-reported endometriosis, P for interaction and subgroup analyses were conducted (Fig. 2). The results showed no significant interactions between the covariates and PHQ9 score (P for interaction > 0.05). The ORs in all subgroups were greater than one, indicating a robust positive relationship between depression and the prevalence of endometriosis. Although the OR was lesser than one in the subgroups with age 20–29 years (OR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.69–1.13, P = 0.296), spinster status (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.85–1.05, P = 0.267), and current smoking status (OR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.93–1.05, P = 0.717), the P value was not significant.

Subgroup analyses on the effect of interaction between the covariates and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 score on the prevalence of endometriosis. P value was calculated by P for interaction and logistic regression analysis. BMI, body mass index. PIR, poverty income ratio.

Discussion

To explore the relationship between depression and endometriosis, we conducted a cross-sectional study of 1395 NHANES participants, of whom 7.17% had self-reported endometriosis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between depression and self-reported endometriosis through independent evaluations. Here, we report that the PHQ9 scores positively correlate with endometriosis prevalence. Particularly, participants with moderate depression exhibited a significantly association with the prevalence of endometriosis compared with those without depression. Our results were relatively robust after adjusting for related covariates. Our findings highlight the role of depression in endometriosis prevention.

Although surgical and drug interventions are currently available for the management of endometriosis, these therapies remain insufficient owing to the high rate of recurrence28,29,30. Depression is strongly associated with gynecological diseases, including endometriosis10. Participants with moderate depression may be prone to self-reported endometriosis, consistent with pathogenic role of PHQ9 reported previously18. In certain situations, depression can contribute to disease progression. For example, severe depressive symptoms are closely associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease31, 32. Notably, women are more likely to experience depression than men33, 34. In patients with chronic pelvic pain, higher depression scores were observed in the physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains, likely reflecting the negative effects of depression on quality of life35. A cross-sectional study showed that depression may postpone menopause by targeting specific biological mechanisms36. Our findings highlighted the influence of depression on the prevalence of self-reported endometriosis.

In this study, age and race were identified as independent risk factors for endometriosis. Population-based studies in China suggest that endometriosis is most common in women aged 15–54 years, with the maximum risk found in the 15–24 years age range; the prevalence of endometriosis subsequently decreases continuously with age37, 38. However, in the United States, the highest incidence of endometriosis is observed in women aged 36–45 years39. In the present study, participants aged 41–54 years had a higher prevalence of endometriosis than those in the youngest age group (20–29 years). This may be explained by the chronic-continuous morbidity pattern consistent with endometriosis. Furthermore, we found that Mexican–American participants were less vulnerable to endometriosis than White participants. Overall, White patients have a higher chance of endometriosis diagnosis than non-White patients40. However, due to access to good medical conditions, White patients had a better prognosis, accompanied by lower mortality and cost compared with patients of other races41.

This study had certain limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study; thus, causality could not be determined. Therefore, it is worth investigating whether depression and self-reported endometriosis mutually influence each other. Second, due to the characteristic features of PHQ9 and endometriosis, only participants in a 1-year cycle (2005–2006) were enrolled in this study, which may have led to selection bias. Third, given the high loss rate in covariate “diagnosis age of endometriosis,” the results may be subject to a certain margin of bias. Finally, sampling errors inherent in the NHANES data cannot be ruled out. Considering these limitations, large prospective cohort studies are required to confirm our results.

In conclusion, we found a strong positive association between the PHQ9 score and self-reported endometriosis. Moderate depression significantly and positively correlated with the prevalence of self-reported endometriosis. Our study sheds light on the risk of depression in patients with endometriosis. Further studies are required to elucidate a causal relationship between depression and self-reported endometriosis.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are freely available from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The data can be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

Abbreviations

- PHQ9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire 9

- MEC:

-

Mobile examination center

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

References

-

Huang, Y. et al. Deficiency of MST1 in endometriosis related peritoneal macrophages promoted the autophagy of ectopic endometrial stromal cells by IL-10. Front. Immunol. 13, 993788. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.993788 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Merlot, B. et al. Pain reduction with an immersive digital therapeutic tool in women living with endometriosis-related pelvic pain: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 24(9), e39531. https://doi.org/10.2196/39531 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Della Corte, L. et al. The burden of endometriosis on women’s lifespan: A narrative overview on quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(13), 4683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134683 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Alborzi, S. et al. Colorectal endometriosis: Diagnosis, surgical strategies and post-operative complications. Front. Surg. 9, 978326. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.978326 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Harp, D. et al. Exosomes derived from endometriotic stromal cells have enhanced angiogenic effects in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 365(1), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-016-2358-1 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Kovács, Z., Glover, L., Reidy, F., MacSharry, J. & Saldova, R. Novel diagnostic options for endometriosis—Based on the glycome and microbiome. J. Adv. Res. 33, 167–181 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Koo, K.-M. & Kim, K. Effects of physical activity on the stress and suicidal ideation in Korean adult women with depressive disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(10), 3502 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Smits, J. A., Minhajuddin, A., Thase, M. E. & Jarrett, R. B. Outcomes of acute phase cognitive therapy in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression. Psychother. Psychosom. 81(3), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1159/000334909 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Han, K.-M. et al. Relationship of depression, chronic disease, self-rated health, and gender with health care utilization among community-living elderly. J. Affect. Disord. 241, 402–410 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Drewes, M., Kalder, M. & Kostev, K. Factors associated with the diagnosis of depression in women followed in gynecological practices in Germany. J. Psychiatr. Res. 141, 358–363 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Youseflu, S., JahanianSadatmahalleh, S., Bahri Khomami, M. & Nasiri, M. Influential factors on sexual function in infertile women with endometriosis: A path analysis. BMC Womens Health 20(1), 92 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

An, S. et al. Comparison of the prevalence of cardiometabolic disorders and comorbidities in Korea and the United States: Analysis of the national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Korean Med. Sci. 37(18), e149. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e149 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bruce, M. L. et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: The Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 175(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5835 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Artom, M., Czuber-Dochan, W., Sturt, J. & Norton, C. Cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of inflammatory bowel disease-fatigue with a nested qualitative element: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 18(1), 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1926-3 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Yuan, L. et al. A survey of psychological responses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic among Chinese police officers in Wuhu. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 13, 2689–2697. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.S269886 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Feng, Z., Tong, W. & Tang, Z. Longitudinal trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression among adults with cardiovascular disease: An analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey 2009–2020. Front. Psychiatry 13, 943165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.943165 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, X. et al. Association between depression and oxidative balance score: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2018. J. Affect. Disord. 337, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.071 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Sun, X.-J. et al. Associations between psycho-behavioral risk factors and diabetic retinopathy: NHANES (2005–2018). Front. Public Health 10, 966714 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Zhang, Y., Lu, Y., Ma, H., Xu, Q. & Wu, X. Combined exposure to multiple endocrine disruptors and uterine leiomyomata and endometriosis in US women. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 726876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.726876 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Xu, N. & An, Q. Correlation between dietary score and depression in cancer patients: Data from the 2005–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Front. Psychol. 13, 978913 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Xue, Y., Xu, J., Li, M. & Gao, Y. Potential screening indicators for early diagnosis of NAFLD/MAFLD and liver fibrosis: Triglyceride glucose index-related parameters. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 951689 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Xu, F. & Lu, B. Prospective association of periodontal disease with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: NHANES III follow-up study. Atherosclerosis 218(2), 536–542 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Buck Louis, G. M. et al. Women’s reproductive history before the diagnosis of incident endometriosis. J. Womens Health 25(10), 1021–1029 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Sasamoto, N. et al. Peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length and endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 27(10), 1951–1959 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Bramhankar, M. et al. An assessment of anthropometric indices and its association with NCDs among the older adults of India: Evidence from LASI Wave-1. BMC Public Health 21(1), 1357. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11421-4 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Haines, M. S., Leong, A., Porneala, B. C., Meigs, J. B. & Miller, K. K. Association between muscle mass and diabetes prevalence independent of body fat distribution in adults under 50 years old. Nutr. Diabetes 12(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-022-00204-4 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Yeung, S. Y., Ng, E. Y. L., Lao, T. T. H., Li, T. C. & Chung, J. P. W. Fertility preservation in Hong Kong Chinese society: awareness, knowledge and acceptance. BMC Womens Health 20(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-00953-3 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Ianieri, M. M., Mautone, D. & Ceccaroni, M. Recurrence in deep infiltrating endometriosis: A systematic review of the literature. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 25(5), 786–793 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Guo, S.-W. & Martin, D. C. The perioperative period: A critical yet neglected time window for reducing the recurrence risk of endometriosis?. Hum. Reprod. 34(10), 1858–1865 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Abesadze, E., Sehouli, J., Mechsner, S. & Chiantera, V. Possible role of the posterior compartment peritonectomy, as a part of the complex surgery, regarding recurrence rate, improvement of symptoms and fertility rate in patients with endometriosis, long-term follow-up. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 27(5), 1103–1111 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Brunner, E. J. et al. Depressive disorder, coronary heart disease, and stroke: dose-response and reverse causation effects in the Whitehall II cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 21(3), 340–346 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Hu, Z., Zheng, B., Kaminga, A. C., Zhou, F. & Xu, H. Association between functional limitations and incident cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality among the middle-aged and older adults in China: A population-based prospective cohort study. Front. Public Health 10, 751985 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Keck, M. M. et al. Examining the role of anxiety and depression in dietary choices among college students. Nutrients 12(7), 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072061 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Silva, L. R. B. et al. Physical inactivity is associated with increased levels of anxiety, depression, and stress in Brazilians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 11, 565291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565291 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Romão, A. P. M. S. et al. High levels of anxiety and depression have a negative effect on quality of life of women with chronic pelvic pain. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 63(5), 707–711 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Li, J., Eriksson, M., Czene, K., Hall, P. & Rodriguez-Wallberg, K. A. Common diseases as determinants of menopausal age. Hum. Reprod. 31(12), 2856–2864 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Feng, J., Zhang, S., Chen, J., Yang, J. & Zhu, J. Long-term trends in the incidence of endometriosis in China from 1990 to 2019: A joinpoint and age-period-cohort analysis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 37(11), 1041–1045 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Liao, K., Luo, B. & Luo, J. The burden of endometriosis in China from 1990 to 2019. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 935931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.935931 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Christ, J. P. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and trends in endometriosis diagnosis: A United States population-based study from 2006 to 2015. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225(5), 500.e501-500.e509 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Jacoby, V. L., Fujimoto, V. Y., Giudice, L. C., Kuppermann, M. & Washington, A. E. Racial and ethnic disparities in benign gynecologic conditions and associated surgeries. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 202(6), 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.039 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Westwood, S. et al. Disparities in women with endometriosis regarding access to care, diagnosis, treatment, and management in the United States: A scoping review. Cureus 15(5), e38765. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38765 (2023).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the NHANES team for their time and work. Thanks to Zhang Jing (Second Department of Infectious Disease, Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital, Fudan University) for his work on the NHANES database. His outstanding work, nhanesR package and webpage, makes it easier for us to explore NHANES database.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number (82305283 and 82305284) and the Siming Research Project in Shuguang Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SGKY-202306). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, or data interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.-W.H. and X.-L.Z. conceived and designed the study. P.-W.H. and X.-L.Z. contributed equally to this study. X.-L.Z. collected the data. P.-W.H. and X.-L.Z. analyzed and interpreted the data. X.-T.Y. visualized the data. P.-W.H. and X.-Z. wrote the original manuscript. C.Q. and G.J.J. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors have read and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, PW., Zhang, XL., Yan, XT. et al. Association between depression and endometriosis using data from NHANES 2005–2006.

Sci Rep 13, 18708 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46005-2

-

Received: 15 January 2023

-

Accepted: 26 October 2023

-

Published: 31 October 2023

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46005-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.