Author Barbara Kingsolver had just stepped away from her desk in her home office where she was logged in for a Zoom interview when her daughter, Lily, logged on from her home in Florida.

Barbara quickly came back into view. “I was coming down the hall and heard Lily talking from my office!” she said, delighted. “It’s really fun to see each other, even on Zoom. … This is the farthest apart we’ve lived in our whole lives.”

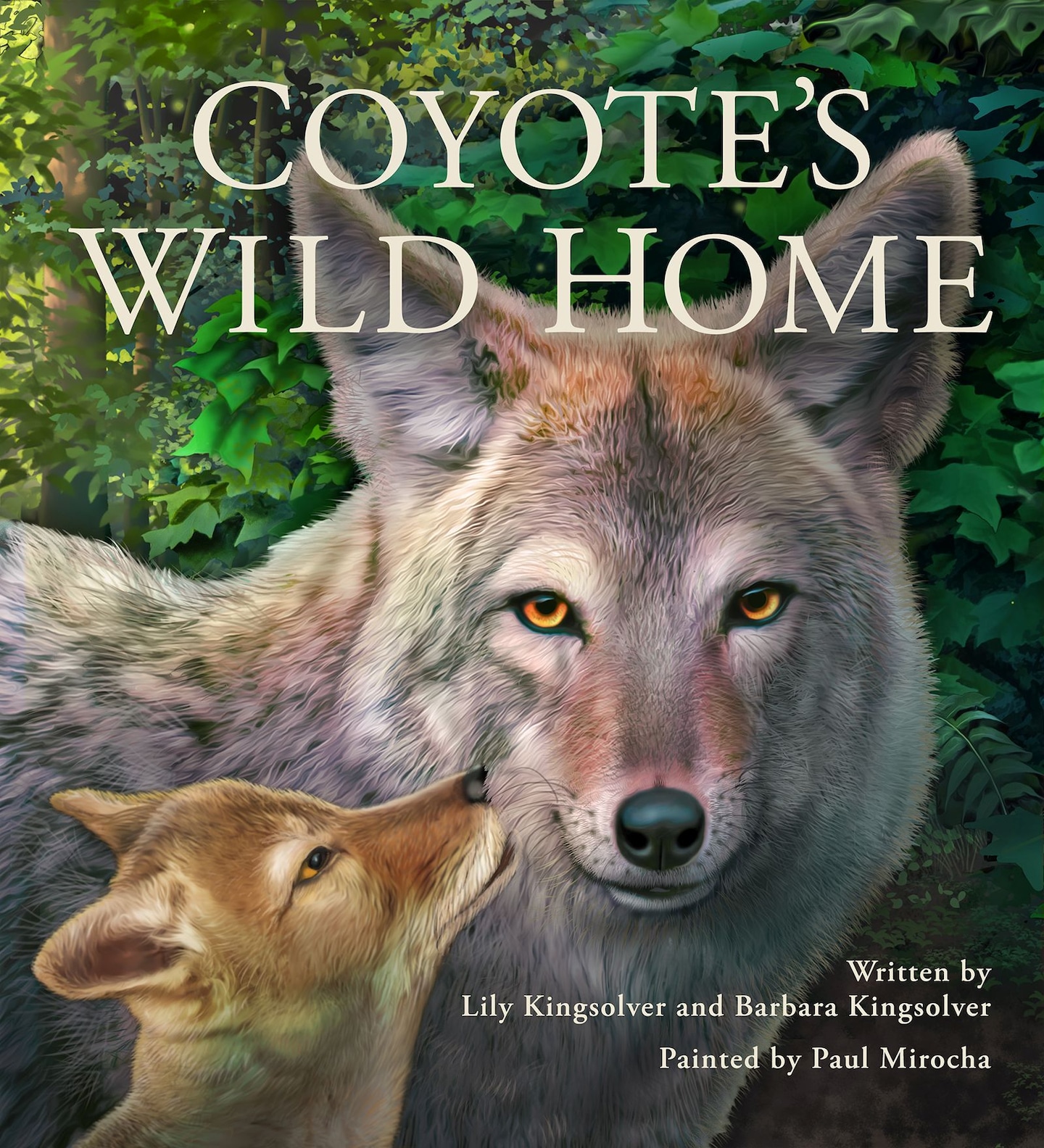

The two Kingsolvers were there to discuss “Coyote’s Wild Home,” a new children’s book they wrote together — a first for them. The book, illustrated by Paul Mirocha, tells the story of a grandfather and granddaughter on a camping trip. The grandpa shows the girl evidence of coyotes and explains why humans shouldn’t be afraid of predators, and why it’s important that they exist.

Lily, 27, grew up in southwest Virginia among the Appalachian Mountains. Now in graduate school at the Florida Institute of Technology, she’s earning her master’s degree in environmental education. Lily’s career path isn’t a surprise after being raised by Barbara, a biologist known for her attention to nature and the environment in her best-selling novels.

“We’ve been doing projects together our whole life,” Lily said. “Mom always got us in there, working on the garden.”

“Or in the woods, hiking,” Barbara added.

Mother and daughter discussed working together on their beautiful children’s book — one that the author of Demon Copperhead said she never could have written herself — and the necessity of educating children (and adults) about the importance of the natural world.

The interview has been slightly edited for length and clarity.

Q: What drew you to write about this topic?

Barbara: I credit Gryphon Press with the origin of this book. They have this mission to publish children’s books that introduce children to the natural world and create compassion and empathy in children. They wanted to publish a book about coyotes, and sent me an email asking if I would be interested because I’ve written about coyotes before.

I actually wrote a novel in which coyotes played a central part. One of the characters was a coyote scientist, and so I had done a lot of research about coyotes and the role of predators in ecosystems. So they thought that was a natural match. I thought, “Isn’t this a beautiful idea? And there’s no way I can do this.”

Q: Were you too busy? Why couldn’t you do this?

Barbara: I’ve actually tried three times to write a children’s book, and I just don’t have that skill set. So I had already drafted an email back to them saying, “I love this idea. I’m so sorry, I can’t do it.”

That letter and that book idea were sitting on my kitchen table when Lily came in and read the letter and said, “What a good idea!” And I said, “Well, it is a good idea, but the predator biology is so complex. How could you possibly fit that into a child-sized narrative?”

And Lily just laid out the plot. The whole thing right there on the spur of the moment. And I said, “Lily, you should write this book.”

Lily: I said I would, but only if we do it together. I spend a lot of time with children, I spend a lot of time reading books. But mom has the Pulitzer Prize-winning knack. And I absolutely could not have done it without her guidance and encouragement.

Q: How difficult is it to go from Pulitzer Prize-winning writing, Barbara, to writing a children’s book?

Barbara: People think that writing children’s books takes a small subset of the skills it takes to write a novel. They’re not right. It is closer to poetry, closer to songwriting. And Lily is an excellent poet.

She has been a writer since she was very young. She was that 4-year-old who would stop an adult conversation and say, “tell me what crepuscular means.” And so I’ve always known that whatever else Lily does, she will also write. Lily was absolutely the first author of this novel.

I feel like I served more as an editor. We turned in our proposal, and they said, this is great, but it’s 3,000 words, and what we need from you in total is 1,500 words.

Lily: And then we cut it down and we cut it down. I’m so used to teaching where you can just say more and more. And so I wanted to fit in this and fit in that. And Mom was really good at saying, no, this is our message.

Q: In this book, a grandfather gently explains the role of animals in nature and why coyotes, in particular, are important to the ecosystem to his granddaughter. Separately, we read about the coyote family. How did you come up with this plotline?

Lily: As an environmental educator, you think a lot about predators [and their] different positions in the world. Because we as humans are in the position of predators, I think we are in a parallel role.

I feel like people’s fear of predators is somewhat based on the fact that we see ourselves in them, and that’s very threatening. We like to be on top, and it’s scary to see something that is also very powerful, that also has a large impact on its environment.

And so I think the story is sort of to position humans in the food chain as well as positioning the coyotes, because I think it is really imperative that we think about how we relate to animals in the ecosystem.

Q: Why is it important to you to be an environmental educator and to write a book like this?

Lily: What we change is based on what we care about. And so early childhood is when you can encourage empathy, when you can start to show children why and how we care about the world, about animals and ecosystems and our environment.

It brings me the most joy when you see young kids hold a worm for the first time or see a bird nest. To just foster these connections between children and their environment, I think that is the first step to addressing the problems and issues that these kids probably shouldn’t know about at their age.

But when they’re older, they are going to face these problems like climate change and habitat destruction and our predators disappearing. And fixing that all begins with empathy.

Barbara: We thought of this as an especially important opportunity to encourage empathy for predators because children’s literature has really done a number on them.

Our folklore and our stories have made predators the bad guys: the big, bad wolf; the big, bad bear. It probably dates back to the time when people really did have to worry about the wolf at the door or eating their sheep, damaging their farm animals.

Of course a coyote still will take a lamb from time to time. But we have pushed our ecosystems into smaller spaces and most people don’t know that predators hold such a crucial position. Which is so much to pack into a children’s book.

Q: So how did you pack it all in?

Barbara: An important revelation as we worked on condensing the text of this book was that a picture really is worth a thousand words. We would take our page of text, and think about what parts of this can be told by the illustrations. We would circle a line and move it over to the illustration side. It was such a great day when we realized the who, what and where could all be told by the illustrations, leaving us with the why.

Q: What else do you want readers to know?

Barbara: The greatest miracle of parenting is that your kids turn into your friends. And when your kid can also turn into your colleague whom you respect, who has skills beyond your own, like Lily does, that’s just the most wonderful thing.