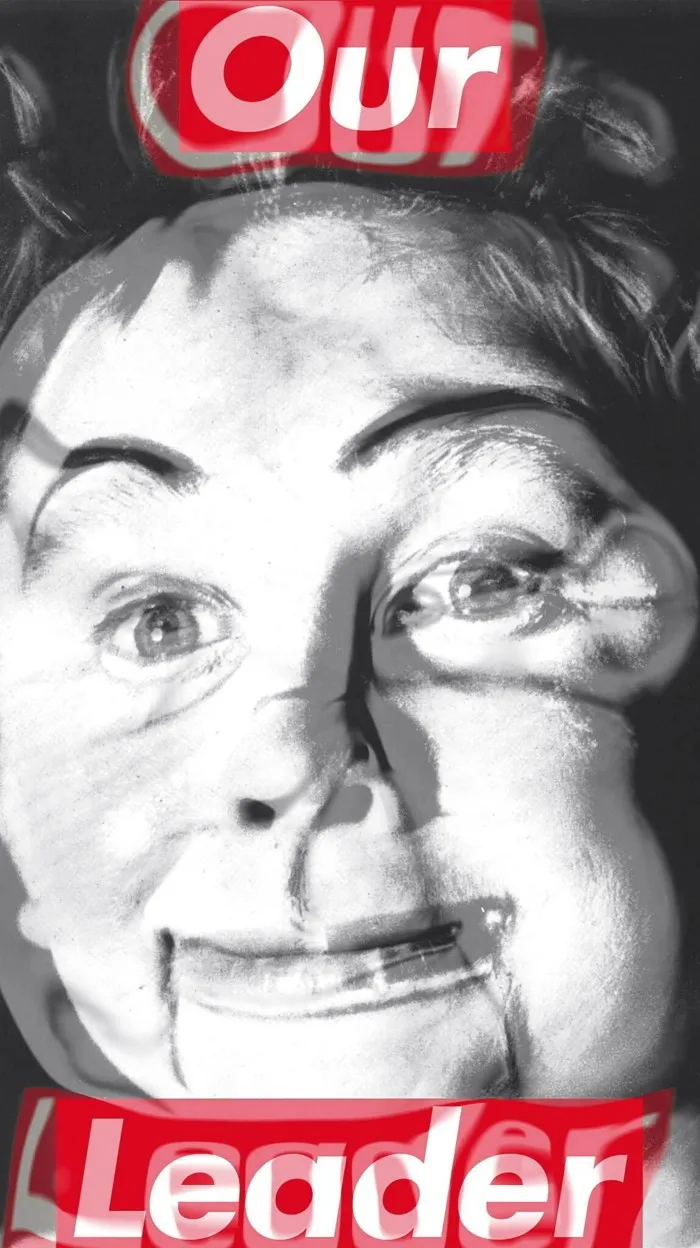

In the first room of Barbara Kruger’s new exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London, entitled Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, the walls are papered with pastiches of the artist’s work. Scraped from Instagram, YouTube and other parts of the social media landscape, they bow to the power of Kruger’s trademark aesthetic: bold white sans serif type reversed out of a brilliant red bar, slapped across a black and white image.

These homages, should we be so kind, also highlight the acuity of the real thing. Kruger is the queen of pith, firing out finely chosen words in short, shouty bursts, bringing Cartesian logic into the consumerist 20th century with her most famous slogan “I shop therefore I am”. Her imitators, by and large, are rarely as fast or furious. Long before Twitter was a twinkle in anyone’s eye, Kruger was employing far fewer than 280 characters to make her points about the social realities of power and gender, race and capital.

“I’ve always had a short attention span,” laughs Kruger when we meet at the Serpentine a day after she’s flown in from Los Angeles. Though nearly 80, with her thick curly hair and general vigour, she could be decades younger. Only her hefty black face mask suggests an ongoing fear of Covid. “I don’t eat indoors in restaurants, I don’t do dinners,” she says. “I just like installing my work, and then I’ll get something in Pret and go back to my room.”

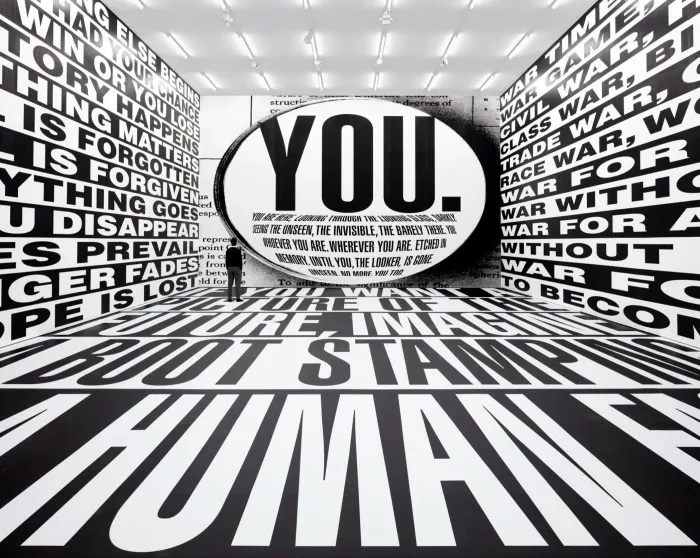

The exhibition is the fourth iteration of a show that she has already modified to fit wildly different spaces in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York. In the last she filled the entire 110ft height of MoMA’s Marron atrium with stretched and strident type, while in Chicago she spread out all over the museum, even inserting a 1997 statue of J Edgar Hoover embracing the lawyer Roy Cohn into the sculpture gallery.

“Statues are about the arbitrariness of history,” she says. “Who gets chosen to be honoured? Cohn was just evil and he was Donald Trump’s mentor. Trump still says, ‘Where’s my Roy Cohn?’” What happens if Trump gets in again? “An absolute collapse of the rule of law,” says Kruger.

The London exhibition occupies the whole of the Serpentine’s original building, in its parkland setting. “Architecture is my first love, and this building has great elegant symmetry, though I’ve had to scale things down here,” says Kruger, who installs through spatial instinct and with the sensibility of a sculptor. “I don’t make models. I just walk in and immediately know what to do.”

Reconfigurations of familiar work include “Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground)”, originally created in 1989 as a banner to be used in the fight for the legalisation of abortion in the US, and timely once again as Roe vs Wade is being overturned bit by bit. Here Kruger has turned it into a digital moving-image work, broken into jigsaw-shaped pieces that pop up and click together, before dispersing and melting away. It suggests both flux and failure. “I wanted to take something that has become very recognisable and change it and move people in a different way,” she says.

It is this resilience and sustained relevance that makes Kruger’s work special. She recycles and reuses, papering the walls and floors of the Serpentine’s gorgeous education space with quotes from George Orwell and Virginia Woolf that she has used many times before, the first a warning about totalitarianism, the second about women’s diminution by men.

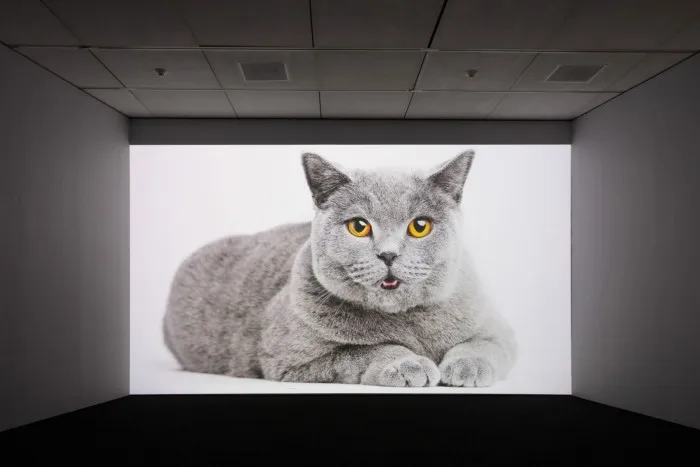

Meanwhile, a 2020 work, “No Comment”, occupies the circular central space with its sweeping domed ceiling. It is a three-channel video installation that fitfully collages footage found on Instagram with the artist’s own work in rapid succession. Everything from hairstyle tutorials to reconfigured city maps — and, of course, cats — flash up on the screens, interspersed with her own typographic interludes.

“The job of dealing with words and pictures was what I did for years at Condé Nast,” says Kruger, referring to various roles at the publisher, as both a designer and picture editor on titles including House and Garden and Mademoiselle. “I learnt a fluency in image and text at my $85-a-week job. Now it’s become organic to me. I wasn’t educated in the codes of art world production or discourse. My work was a reflection of who I was in the world, and you didn’t need a PhD or an MFA to understand it.”

You also didn’t — and don’t — need to go to an art gallery to see a work by Kruger. She has frequently co-opted billboards all over the world, translating her slogans into the local language. She’s not averse to making magazine covers or T-shirts. It is partly this public positioning, rocking between art and commerce, that has made her work so accessible, now amplified a million times over through social media. When the streetwear brand Supreme guilelessly co-opted her formula for its logo in 1994, it was as though it was an available part of the public realm. Kruger has never objected. In London, from February onwards, her work will flash by on the sides of three black cabs, while the enormous ultra-high-definition screen at the Outernet on Charing Cross Road will show a work called “Silent Writings” on selected Monday evenings from March 4.

Between 1985 and 1990, Kruger wrote about television in the American magazine Artforum. She is still a watcher, primarily of reality TV. “I follow Vanderpump Rules, the Housewives of various locales,” she says. “It’s not about liking it, it’s about seeing how people choose to perform themselves in public. To see the brutality and the cruelty. We’re living in an incredible time — which is a car crash of narcissism and voyeurism.”

Consequently, she didn’t want to have her portrait taken to accompany this feature. “I look at screens a lot, but I don’t feel like being captured that way,” she says. “Though I think most people need that, or think they do.” She mentions that, in her brief period of art education at Parsons in New York (she never graduated), she was a student of photographer Diane Arbus. “I respected her as a person but was never a fan of the work.”

Indeed, where Arbus showed the marginal and the outcast, Kruger seems to want to bring her viewers together. As she focuses on gender and inequity, vanity and violence in her work, it functions as a rallying cry, for us to see ourselves within it. It is the art of inclusion. For the Serpentine, she has even produced a TikTok filter that anyone can access. It says: “We are not what we seem”. In these turbulent times, let’s hope she’s right.

February 1-March 17, serpentinegalleries.org

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen