In the aftermath of my father’s death, I wanted only quiet. I chased sanctuary through shadows. I walked the vanishing miles. I lay awake in the midnight hours, but even then, a nearby fox would call out for love, or a deer would high-step through fallen leaves, or a squirrel would bumble in the gutter.

I didn’t mind the birds of dawn, but I minded the eradications of tree surgeons—the carburetor rage of their chainsaws, the thonk of severed limbs hitting the ground. I minded the boot of the boy who smashed the trash bins until they crashed—spilling a bell choir of bottles. I minded the neighborhood girls’ pissing accusations—You’re such a thief, you’re such a liar, you stole my phone, you’re such a liar. I minded the keel of the news and the yawp of the sun. I minded the pretension of narrative, words upon words—how, even when no one was near or no one was speaking, there was a terrible howl at my ear. Worse than consonants. Louder than vowels.

When story returns after story quits, it arrives in fits and fragments, rushes west, flusters east, is soft, invincible fury.

I had been reading Virginia Woolf before my father died, before I rushed to him as his final storm set in, the despair of his lungs in their drowning. Turning her pages. I had been reading Virginia, also Leonard. The long swaying arms of the searchlights over their street called Paradise, in their England, 1917. The clattering machinery of the German Gotha bombers and the ascending cries of the sirens and the putter of the Royal Naval Air Service squadrons and the puff-pop of the smoke where the bombs had succeeded. A letter, sent by Virginia, to her friend Violet Dickinson, bearing news: She and Leonard have bought a table-top letterpress from the Excelsior Printing Supply Co. They are about to hand-build books of their own. Manage the text, command the art, tighten the bindings. Although the letterpress is broken when it arrives, and there are but a scant sixteen pages of how-to’s to get them through the early days. They eye the letters in reverse (Caslon), take the quoin and composing stick into their hands, and decide: Virginia will set the type and bind the pages, Leonard will ink and pull. It will unfold in the dining room of the house where they live, a place called Hogarth.

Play, Leonard will one day say of the thing, sufficiently absorbing. Calming the noises inside Virginia’s head.

Type in her composing stick. Ink on her fingers.

A thin red thread in the eye of her needle. Punch.

Sew.

Salvation.

*

In the aftermath of my father’s death, I bought paper, thread, acrylic paints. Needles, brayers, buttons. Instructions I discovered I could not follow on the form and beautification of blank journals. I awled and bone folded. Knotted and snipped. I made my mistakes at the kitchen table and beside the sink, beneath bare bulbs and in swaths of sun, in the early mornings when I would wake to the fox that lived by the shatter of the moon and was bereft with love. I was not setting lines, not administering hyphens, not placing Caslon between margins. Still, I was sufficiently absorbed: color, paper, knots; ghost prints and ephemera. There was stain on my clothes and waxed linen in my needles. My hands were cracked and raw.

When story returns after story quits, it arrives in fits and fragments, rushes west, flusters east, is soft, invincible fury. I punched and patterned, tore and blended, stole flowers from the garden to preserve them. Is it like this, then, or could this be true—the hands matriculating the rage, arting the heart, deposing meaning?

Fractions arranged. Thread kettled.

Red approximating blue. Salvation.

An amateur obsessive.

*

Before my father died, when he already wasn’t well, I grew frustrated with Virginia. I was reading her fiction by then, her To the Lighthouse. I’d sit in my bed, early in the day, and hear myself yak back at her—cut the vines of her sentences, her looping plentitudes, her times passing. I’d find an easier novel and abandon Virginia, and then I would return. Float into her sea and ride: billows and breakers, tide and tug, the nether and the offing.

I’d yield. It was the only way I knew to read Virginia, although sometimes, whirlpooled into the length of a single Virginia sentence, I’d find that I was drowning. That I could not understand Virginia.

And yet: On the eve of covid-19, my father older than he’d ever been, my father in the early phase of passing, I went to the Kislak to visit Virginia. To hold what she’d made with her hands in my hands. To reckon with what remains when those we battle with, and love, go missing. I’d wait inside that clean box of that reading room for Virginia’s letterpress work to be retrieved. At a long table before an assembly of soft supports that hold the archived and retrieved in a non-spine-breaking V, she came.

Her thick and desiccated pages. Her assertions of ink.

Her chipped and fraying bindings. Her nether and her offing.

I held what she’d made with her hands in my hands. I pretended permanence.

We go to books for solace, and for proof, to begin again at the beginning. Handmade books, first editions, inky manuscripts, especially. They carry time forward on their own electric currents. They keep what we can’t keep. They counterweight the dying.

Thumbprints. Center knots. Errors.

That crease in the top corner.

The infuriating riddle.

Hold the old book in your hand, and you are holding something living.

When the famed Philadelphia bibliophile A. S. W. Rosenbach (1876–1952) was eleven years old, he bought, for the grand sum of $24, an illustrated copy of Reynard the Fox. Young Rosenbach didn’t have the necessary cash on hand, but he had the support of a book-obsessed uncle, in whose shop on Commerce Street the boy had been working since the age of nine. A deal was struck. A book was won.

They carry time forward on their own electric currents. They keep what we can’t keep. They counterweight the dying.

In “Talking of Old Books,” reprinted in Books and Bidders: The Adventures of a Bibliophile, Rosenbach remembers the early undertow of what would become his lifelong obsession:

At that age I could hardly realize, spellbound as I was, the full quality of mystery and intangible beauty which becomes a part of the atmosphere wherever books are brought together; for here was something that called to me each afternoon, just as the wharves, the water, and the ships drew other boys who were delighted to get away from books the moment school was out.

Rosenbach was, in the words of Vincent Starrett, a writer for the Chicago Tribune, “an excellent bibliografer, something of a scholar, and a bookman who would have lived by books, for books, and with books whatever his station in life might have been. It was his initial love and knowledge of old books that made it possible for him to become the great figure known as ‘the Doctor’ in the auction rooms of Europe and America.”

And what a figure Rosenbach cut—a University of Pennsylvania graduate with a Ph.D. in English literature, whose book-acquiring adventures were often front-page news. Over the course of a life that never swerved from rare books, he held the manuscripts of Chaucer, Lewis Carroll, and James Joyce in his hands (not to mention a considerable number of Gutenberg bibles, the copy of Moby-Dick that Herman Melville presented to Nathaniel Hawthorne, and a letter from Cervantes); amassed a fortune in children’s books (most of them donated, toward the end of his life, to the Free Library of Philadelphia); fed the bookish appetites of such men as Pierpont Morgan and Henry Folger; named his fishing boat First Folio; wondered why no wife of a U.S. president had become a genuine book collector; and “made it a rule,” as he writes in A Book Hunter’s Holiday, “to look at any book which is directed my way.” His final Philadelphia residence, in the twentieth block of Delancey Street, is now the home of the Philip H. and A. S. W.

Rosenbach Museum and Library, and it is here where book lovers can, by appointment, see some of the books, letters, and manuscripts Rosenbach could never quite part with himself.

Dard Hunter, in his dusty shoes and hat, his workman’s shirt and tucked tie, traveled the world in search of not just paper but rare books written by other paper lovers. Rosenbach—cigar smoke rising, whiskey swirling, millionaires waiting—dominated auction rooms. They were men of their times, bound by the thrill of the chase and the deep reprieve of history and the hope for the eternal.

__________________________________

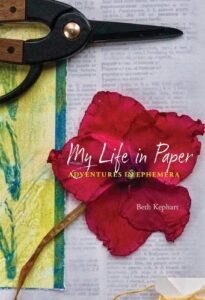

From My Life in Paper: Adventures in Ephemera by Beth Kephart. Used by permission of Temple University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Temple University. All Rights Reserved.