This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

I have read Annie Dillard’s classic essay “Total Eclipse” purely for the sake of the story—to stand on the hill beside her while the world howled itself into darkness and then reclaimed the light. I have read it to map its multitudes—the iterative ways in which the total eclipse is summoned and evoked, fantasized and explained. I have read it to track its recurrent images—the “Arcimboldo idea” of a clown’s face, for instance, or the child’s sand bucket and shovel.

But it was only a few weeks ago, preparing to teach the essay, that I wondered what might happen if I read with the singular purpose of tracing the shifting observational lenses that Dillard deploys across her pages. How, in other words, is Dillard seeing as the piece unfolds? What stance does she take in relationship to each moment in time, herself, and the reader? How does the fluid nature of her many observational lenses impact our experience as we watch, with Dillard, the moon come between the earth and the sun?

The margins of the essay soon filled with the dark-ink scribble of my handwriting, and notes, in part, like these:

Observer as gatherer of the odd detail

Observer as rational, orderly person

Observer as measurer of the sky

Observer as one establishing her bearings

Observer as one who believes in what she cannot see

Observer as fantastical seer

Observer as one who, in awe, loses her sanity

Observer as one who, in awe, scrambles reality

Observer as one capable of seeing prehistoric time

Observer as metaphor maker

Observer as one who sees how another sees

Observer as one who finally turns away from seeing

Really? I thought, when I completed the list. One writer, one single essay, and so many ways, to quote John Berger, of seeing? But maybe I should not have been so surprised. Maybe, before I’d gone on my literary expedition, I should have read (again) from Berger’s Ways of Seeing:

We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are.

The possibilities of the observational lens and the plastic nature of Dillard’s eclipse became, in class, a conversation of wild proportions. What had I missed? What other ways is Dillard seeing? What happens if we begin to read whatever we are reading by hunting down and naming (at least for ourselves) the author’s observational lens(es)?

And what if, as we write, we become cognizant of our own observational lenses. If we write in other words, keenly attuned to the lenses we are applying?

“Two hundred words,” I said to the class as we closed. “Come back with two-hundred words that are about the act of seeing. We readers must be able to see your object or relationship with crystalline clarity. We must also be able to see, to name, the lens you applied to your seeing.”

In listening, a few days later, to the fabulous prompt-initiated passages, we saw each other newly. We were, we realized, writers looking through the lenses of archeology and symbol. We were writers whose filters were hue and the impression left by footprints in the grass. We were writers who did not just see, but writers who understood how we were seeing.

I never know what’s going to emerge in the wake of a prompt. I sit where I sit—hopeful, awed. In the wake of that teaching week, I began to wonder about my own work. How I see, and how I express my own seeing. Which observational lenses I bring to my telling.

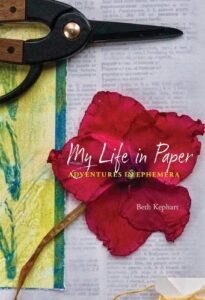

My Life in Paper: Adventures in Ephemera, my newest work, is a book I have yet to be able to explain in a single, clarifying sentence. Sometimes I describe it as an exercise in hybridity—the memoir in essays meets the epistolary memoir meets the amateur artist and paper obsessive. Sometimes I say, in a bid at economy, that it’s a book about how paper holds and shapes our lives. Sometimes I say it’s a book about all the ways I’ve failed and all the ways that I’ve kept trying.

We were writers who did not just see, but writers who understood how we were seeing.

But maybe I should have been saying, during all this time of floundering self-promotion, that My Life in Paper is an exploration of the observational lens.

Observational Lens One, the dominant lens, features the mystified self peering through the bent glass of time toward the mystifying self. This is me as memoirist, whose choices and habits and minor wars require a shifting negotiation between who I was then, who I might have been, and who I became. Sometimes I manage to do this negotiating in the first person. Sometimes, as in a scene sparked by the memory of a paper sewing pattern, the only choice is to meet the past as a third-person narrator.

…the daughter has her deficits. More than anything her acrid awareness of her many deficits. This knowing curved into the slump of her shoulder blades and into the stiff-legged way that she walks right up to the edge of things, where she will stop, no faith at all in her own physicality or charm, in her ability to expand a room by others’ happiness to see her, except for when she is on the ice, when she is ice skating.

Observational Lens Two, that epistolary lens, reveals the confession-prone self who discovers that she cannot adequately grapple with life’s big questions—obsession, possession, ambition, understanding, and yielding, say—until she imagines herself into a conversation with the late Dard Hunter, the greatest paper hunter and historian of the recent past. This observational lens is waver and uncertainty. It is shiver and in-motion, not fully grounded. It is the need to ask, to compare notes, to divulge to someone who might care, someone who (in the writer’s mind) is somehow listening. As in this passage:

What is lost is lost, and every successive comeback is mere tarnish, and we are saved by our own estimations by the kindness of another—a letter, maybe, a story—and so I’m writing this to you because I’m thinking about you, at the end of your life, your body playing tricks. The cortisone they gave you for your condition sometimes blunting your imagination. Your six feet tall carrying 128 pounds weak. Your blind eye still blind, your other eye hurting. Your hale and hearty million-miles body; your farming, moulding, deckling, couching, cutting, setting, walking body; your crushed into cargo holds, squeezed into railway cars, there among the ox carts body; your hand that ceded to the hand of Gandhi body; your heart that survived the dying of Edith body—that body refused to lift one foot and then the next to climb the tall stairs in your own home by the end of your long living, Dard.

Observational Lens Three, is the lens of rationality, objectivity, of knowing gathered from the pages of history, from scholars and thinkers who have gone on before me. This is the lens that is applied to the notes that ground most of the memoiristic passages in my book. Here again is Sewing Patterns, but now the writer is the observer who is standing on both feet. Calm. Clear-eyed.

But it was a woman who, with the enterprising support of her progressive husband, engineered the first mass production and wily distribution of sewing patterns, both in the United States and abroad. She’d made herself sound French—Mme Demorest—but Ellen Louise (1824-1898) was in fact a native New Yorker, the daughter of a hat maker, a once-flourishing milliner operating her own high-fashion establishment, and the second wife of that progressive widower, William Jennings Demorest.

The observational lens is, I think, related to voice—to tone and mood, grammar and syntax and diction—but it is also something more. It’s the stance we take toward the things we choose to see. It is how, in other words, we yield our looking to the reader beside us, how we bring them into our world.

___________________________________________

My Life in Paper: Adventures in Ephemera by Beth Kephart is available now via Temple University Press.