When a dead author has one of their novels made into a film, they get let out of the underworld for a season, though usually they return in their most familiar forms. Since Yorgos Lanthimos adapted the novel Poor Things by the late Alasdair Gray—winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and getting a worldwide release this December—Gray’s greatest hits, Lanark and 1982 Janine, are back on the shelves with those distinctive covers he illustrated himself (not counting Poor Things, reissued with Emma Stone’s stare on the front).

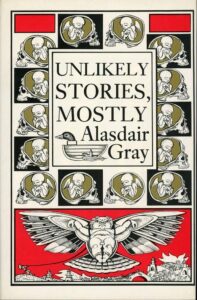

I could write reams on why all three novels deserve to regain a place in the sun. But lesser-known works by Gray deserve a place, too: Unlikely Stories, Mostly, a collection of short stories that includes the best he wrote; The Book of Prefaces, a gargantuan retelling of the history of English literature through its first pages; and his purposeful bowdlerization of The Divine Comedy, whose final volume, Paradise, was published, appropriately enough, after his life.

*

Unlikely Stories, Mostly—according to critic Douglas Gifford, who helped write the postscript—is a book of two halves. The first half describes a Portrait of the Artist arc from childhood onwards, beginning with “The Star,” an apt opening chord for Gray’s work, with its fairytale combination of a solitary boy in humble circumstances who discovers, harbors, and succumbs to the magical. “The Cause of Some Recent Changes” is set in the sort of art college Gray himself studied at, minus the secret underground institute, which he elaborated on for Lanark. “The Comedy of the White Dog,” about young men bested by a surprising love rival, has the frank yet surreal sexuality of an authentic folktale. But it was with “The Great Bear Cult,” which tells the story of a pre-war craze for dressing up as teddy bears to smuggle in an allegory about England’s flirtation with fascism (while also predicting Furries) that Gray settled into another, and his most characteristic, mode for the book’s second half.

The “epic” was Gray’s watchword, his novel Lanark being an attempt to write one for his Scottish homeland; but his greatest epics are the five stories that comprise the back half of Unlikely Stories, Mostly. “Five Letters from an Eastern Empire” starts as an orientalist fantasy, with the comic poet Tohu and epic poet Bohu summoned to the new capital to await the Emperor’s theme for their work, and ends as a heartbreaking satire on the power and paltriness of art. In “M. Pollard’s Prometheus,” Monsieur of the title woos a soixante-huitard Parisian by comparing himself to God and trying to engage her help in rewriting Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound; but he’s not a god, nor much more than a stand-in for lonely Gray.

It’s Gray’s most tricksy and tricky story, barred in columns and triangles of text that overlap pages.

Most of the time Gray’s sentences are classically balanced (you never trip on a word), but he was also a ventriloquist of what Scots call bletherers: one such is Sir Thomas in the story named for him and his “Logopandocy.” It’s Gray’s most tricksy and tricky story, barred in columns and triangles of text that overlap pages to house Sir Thomas’s pros and cons about himself, his nation, and his fellow windbaggy countrymen (including one Hugo De Grieve, who “made some 32 books of verse wherein antique and demotic tongues, political rhetoric and all the natural sciences are by violence yoked together to deny, prophetically simultaneously and retroactively every conclusion he arrives at, except this: that the English are a race of Bastards”). But the tricksiness is warranted: Sir Thomas longs to clarify these cacophonies through a language he’s invented that will mend the fissures of Babel.

But it’s in the Babelesque story “The Axletree,” told in two halves bookending this five-story sequence, that Gray is at his epic best. Another Emperor features, this one hoping to solve the problem of imperial collapse by constructing a never-ending tower, the top of which, unfortunately, touches the heavens. With its Hebrew cosmology and deluging finale, the story shares much with Ted Chiang’s award-winning “The Tower of Babylon” from a decade later. But that simpler and smaller-scale story—notwithstanding its massive tower—doesn’t have half the poetry of Gray’s, with its finger-melting sky in “slender rippling rainbow” colors. Neither does it have the same scope; via the story of the tower, Gray condensed Western history in the time-trotting style of Jacob Bronowski or E H Gombrich. Yet he made sure the story was overdetermined enough not to be an easily dispatchable allegory. And just when the hand of its politics gets heavy, the story ends with one of the most awe-ful revelations in literature.

*

In both “The Comedy of the White Dog” and his afterword to Lanark, Gray described the sort of compendious, socially improving personal libraries of working-class Scots which he himself was raised on, where works of Lenin rubbed covers with the classics. It’s in that democratic spirit that he edited an anthology of prefaces to works of English literature, starting with Caedmon’s poem of the seventh century through to Wilfred Owen’s war poetry 14 centuries later, and stopping only in 1920 at the wall of copyright.

In his own preface Gray listed reasons for reading the book: “Seeing great writers in a huff,” “The biographical snippet,” “The pleasure of the essay,” “The pleasure of hearing great writers converse,” and “The pleasure of history.” There’s a gossipy Letters-of-Note draw in reading Charlotte Brontë spend her preface to Shirley drubbing a hostile reviewer. Other authors in preface-form sound like a soldier put “at ease”; see Mark Twain griping about Persons looking for Moral or Plot in Huckleberry Finn. Others get amusingly candid, as when Benjamin Franklin prefaces his Autobiography with the admission that “Most People dislike Vanity… but I give it fair Quarter.”

There’s a gossipy Letters-of-Note draw in reading Charlotte Brontë spend her preface to Shirley drubbing a hostile reviewer.

It’s the last reason Gray listed, however, “The Editorial,” that is the book’s unique selling point. Each preface has a sidebar of commentary, while each new era of literature is set off with an original essay. This might make The Book of Prefaces seem like another of those single-volume histories of English literature, but in its case, the commentaries and essays are openly tendentious (a relief compared to so much perniciously neutral nonfiction).

While it never gets as political as Gray was in life, the book charts how economics, war, and tech are drivers of literature as much as individual genius. At the same time, it’s a loving tribute to those same individuals, to the embers they left in the past that became sparks for the future. As The Faber Book of Reportage is to journalism, The Book of Prefaces is to literature: an epic but humbling record of all the many lives that go into making history.

One reason Gray didn’t list for reading the book is its beauty. As one of his obituarists wrote about Lanark, “A words-only version without the elaborate plates would be tantamount to an abridged edition.” Gray’s illustrations for The Book of Prefaces are just as essential, for one theme of its commentaries is how much community matters in the production of any great literary work. Gray explains he would have never met his deadline for The Book of Prefaces had he not employed his academic and writer friends to help. He honors each with portraits that panel the book with as much prominence as the humanizing ones he drew of its famous authors. A team effort to produce something unique, useful, and beautiful: Alasdair Gray’s socialism at its best.

*

Vladimir Nabokov once ranked the three sins of the literary translator:

The first, and lesser one, comprises obvious errors due to ignorance or misguided knowledge… the next step to Hell is taken by the translator who intentionally skips words or passages that he does not bother to understand or that might seem obscure or obscene… The third, and worst, degree of turpitude is reached when a masterpiece is planished and patted into such a shape, vilely beautified in such a fashion as to conform to the notions and prejudices of a given public.

By these standards Gray’s skipped and patted version of Dante, which from its title—The Divine Trilogy, not Comedy—onwards is nothing short of a re-write, would send him straight to Hell (as he renames the poem’s first volume, from Inferno).

But he didn’t really translate The Divine Comedy. Rather, he made a retirement hobby of paraphrasing existing translations, since “having written over 20 books, mostly fiction, [I] had no ideas for more, and could imagine no better exercise for my verbal imagination.” He did skip out the seemingly obscure, though more as an admission of his limits: “cut it down to the range of my own intelligence, which is certainly less than [Dante’s], but more equal to your own, so more easy to understand.” Making it easier to understand also meant writing an “Englished” version, as Unlikely Stories, Mostly commends Muir of Orkney for doing with “The Tribulations of the Prague Rabbi” (a reference to Kafka’s first, and loosest, English translator).

Gray couldn’t have picked a better project to sign off with.

It’s almost comical that such a lettered writer with his storied career ended it with the equivalent of an abridged classic or “plain English Shakespeare.” It can just about be defended as a useful primer to Dante’s hope-abandoningly allusive text. A stronger defense would emphasize Gray’s own poetry. Never considered a major poet, he nonetheless published several chapbooks and was a dab pen at everything from light verse to pastiches of Milton and Marlowe. His version of The Divine Comedy mixes the ethos of the ordinary-language poets with wordplay and internal rhymes: “The love-light in the face of Beatrice/ transhumaned me in ways I cannot say.”

Seen as a translation, his Dante is a travesty. But seen as an adaptation, it has a cover version’s relationship to the original song: both a tribute and a revamp. And no wonder Gray chose to cover Dante. Doing so was, in the words from 1982 Janine, such sweet homecoming. The Divine Comedy was one of the inspirations for his break-out novel Lanark; he wrote admiringly of its “truly encyclopaedic achievement. It equally presents the religion, philosophy, politics, poetry and science of Greek, Roman, Jewish and Christian Europe as a historical, Catholic continuity,” words in turn that could stand as a description for his short story “The Axletree.”

Having spent stories, novels, plays, and poems decrying corrupt cities and states, imagining gods and Dante-level hells (he once filled a page of a novel with the word “hell”), and questing for redemptive love like M. Pollard and Dante before him, Gray couldn’t have picked a better project to sign off with. It might not secure his place in writers’ paradise, but it’s no mortal sin.

*

In his lifetime Alasdair Gray never secured the broad readership his talents deserved and for which he’d hoped. (He turned down a knighthood not because he was for Scottish independence but because there was no money attached, or so he joked.) The success of the film Poor Things will be a boost for his publisher, Canongate, but too late for him. Posthumous popularity can’t console the dead. But hopes outlast their hoper, not least when they’re yet to be fulfilled. Gray’s Sir Thomas told his diary that he’d prepared himself “to write a book the world would not willingly let die.” We shouldn’t willingly let these books die either.