Cleo Qian and I met about six summers ago in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, when Qian sublet a room from my old roommate. Our discussions revolved around dating, writerly aspirations, and the city itself. After Qian moved out, we kept in touch. She later helped me find another room, in a different apartment, in a separate section of Brooklyn. Qian steadily published short fiction and poetry, and I eagerly read her new pieces, which often featured relationships tinged with melancholy.

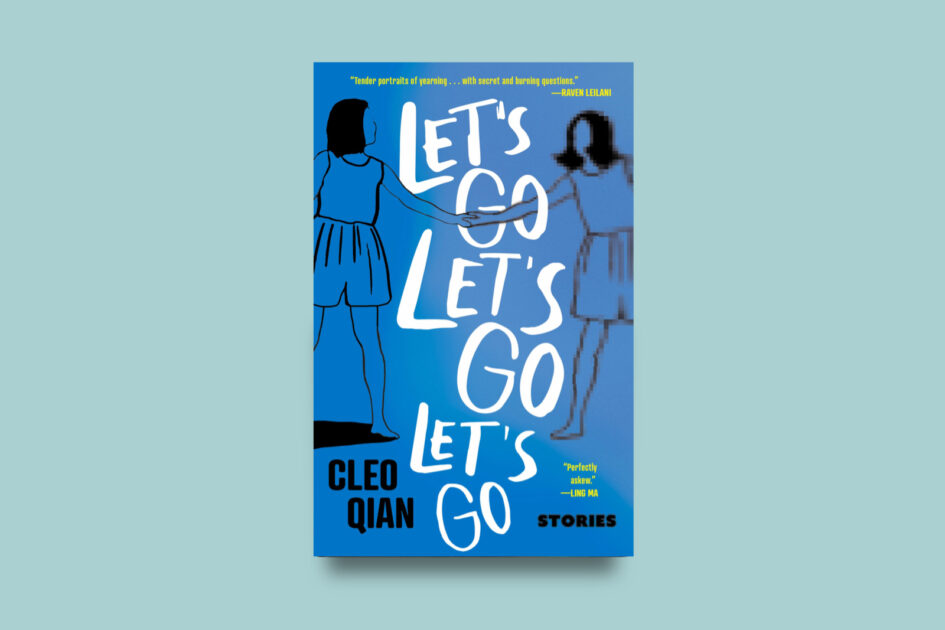

Qian’s hard-won debut Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go (Tin House) includes eleven new and previously published stories. Alternately realistic and speculative, they feature young women grappling with friendship rifts, unequal romances, and desires to escape. Four stories follow the same protagonist, Luna, who contends with conflicts and disappointments as she ventures from southern California to a teaching gig in Suzhou, China to Brooklyn and back again. One Luna story, “Chicken. Film. Youth.,” which leads off the collection, was selected by Ling Ma for 2nd place in the Zoetrope 2022 Short Fiction Competition.

In late September, Qian visited Los Angeles, where I now live, to promote her book. She now splits her time between New York and Chicago. We met at a Filipino restaurant and both ordered a Worker Wednesday Plate, which allows you to sample many offerings at once. Qian’s friend joined us halfway through. Before we veered into more serious book talk, Qian and I discussed mutual friends and acquaintances, our continued dating efforts, and our relatively new jobs. Qian seemed surprised to find herself gainfully employed and quite successful in her non-literary field. Together we wondered why being good at one’s job seems at odds with being an artist. The American system, Qian said, isn’t set up to support creativity. And yet the American MFA program isn’t really set up to valorize 9-5 employment in a non-writing position, either.

—Alina Cohen

Alina Cohen How did the book come to be?

Cleo Qian In 2021, I finished the novel I’d been writing for five years. It was so bad, I threw it away. The novel had been my lifeline—I kept saying, “Once I finish this, I will get an agent and a big book deal, and I will finally rest.”

I became depressed. I had a bad relationship with writing. I distanced myself from a lot of writer friends. They believed in me and loved me, but I needed to participate in other scenes. I wanted to be a writer my entire life, and I started asking, What does it mean if I stop writing?

I still had a draft of this short story collection sitting around. I finished it in 2020, queried it, and got no responses. I began querying agents again, but they wanted a novel. This was my dark night of the soul, being like, I will never have a book out in the world.

I’ve published a lot of short stories and non-fiction pieces online. Other people—white people—who’d published less were getting agents and $800,000 book deals. I couldn’t beat the racial dynamics in publishing. But the same instinct that told me the novel was bad also told me the short story collection was good enough. I submitted my manuscript to the Tin House open call and they took the book in July 2022.

AC What positive things came from working on the novel?

CQ It taught me that you always have to be doing something new. My grief made me develop a healthier relationship with writing. I took poetry and dance classes. I tried aerial trapeze and other circus arts. I traveled. I listened to new music. I immersed myself with people in the visual arts, design, and architecture world.

A lot of people don’t care about writing. They don’t read. It means nothing to them that you’re a writer. A huge part of my person isn’t tied to writing, and it was refreshing to develop my personality outside the literary world.

Many writers throw away novel drafts. If I write another novel, I’ll be able to approach it with more experience.

AC You write about many specific subcultures. You’ve got Asian American twenty-somethings in Los Angeles, gamers, an American student teaching in China, a Chinese radio host and a K-pop star, Japanese students in the wilderness, and Brooklyn hipsters. To me, there’s a connection between this and you saying, I can’t write right now, I’m taking a trapeze class.

CQ I wrote these stories from 2016 to 2022. In my own life, I was experimenting and testing out new identities all the time. I thought a lot about subject matter. There are many people who find literary fiction insular and narrow. I think part of the writer’s duty, in addition to being good at your craft, is to live and think broadly. Otherwise, who are you writing for?

AC “Monitor World” and “Power and Control” felt like sister pieces. They’re both about some pretty dark romantic relationships.

CQ That’s true. Both of them have pretty bad relationships where one person is being lied to.

AC You write about young women with mismatching desires for closeness, especially in Luna’s stories. How do you consider female friendships in context with your other major themes: alienation, the desire to escape, and the uncertainties of youth?

CQ Some reviewers suggested that Luna’s relationships with female friends who aren’t as close as she might wish are symbolic of queer longing. It’s not that clear cut. Luna isn’t sexually attracted to those friends. Maybe because Luna feels alienated, she longs to be known. It feels bad when her closest friends have other priorities.

Many young women tell each other everything. They can’t wait to go home and tell their friends about a date. Sometimes, telling the friend the story is more exciting and fun than the actual living. I’ve seen that with many people, especially women, queer or not.

Female friendships can include melding. When that melding stops, and people begin to differentiate from each other, that’s hard for Luna. This is especially true because she doesn’t trust her romantic relationships. She puts all her trust into her friendships. It hurts her when friends behave badly or don’t understand her. She feels that you’re allowed to be upset if a romantic partner doesn’t understand you, but if a friend treats you in a way you don’t like, there’s less of a script. In many ways, we’re expected to hold friends to lower standards.

AC I was enchanted by “The Girl with the Double Eyelids.” The story hovers in a mythic, fairy tale-ish setting. The main character, Xiao Yun, gets double eyelid surgery and suddenly sees these strange tattoos on people that suggest their secrets. Towards the end, she says, “There were emotions in me, suspicion, fear, doubt, hurt—if I had to articulate them, I would articulate them as images, a heavy umbrella, a lichened boulder sunk into a sea hole.” Is there a relationship between what Xiao Yun can do and writing itself?

CQ Xiao Yun has the ability to see images on people that give her a key to their inner emotional lives. The problem is that she can’t interpret the keys. My stories often come from some disappointment or conflict in my own life, and I’m writing to figure out what happened. I have this wistful feeling that if I really knew that other person, I could have avoided the pain of conflict.

AC How did that story develop?

CQ The double eyelid surgery hasn’t been written about much in America, yet I, as a Chinese person, have had a lot of pressure to get it. At first I was thinking about beauty and the costs of these expectations on appearance. Then I had this fun idea, What if someone got this surgery and then could see things? It only gradually became a coming-of-age story. Xiao Yun tries to figure out the adults around her and what kind of life she wants. She discovers that the adults aren’t happy, and some are morally compromised, which is a shock to anyone growing up—What? My parents don’t know everything? I still have not recovered from that shock.

AC “Chicken. Film. Youth.” has a winning, intricate structure. We think we’re reading one story—about a few friends out to dinner—and it turns out we’re reading another, about the restaurant owner, who was an experimental filmmaker. Themes of youthful desire and ambition link the interwoven stories. Was all this difficult to calibrate?

CQ Editing it was hard. There are so many characters and nested narratives and slippery identities. The story began with four friends in their late twenties wondering, Did we use our youth properly? Then they get a glimpse into the experimental filmmaker’s perspective, which is that he’s a disappointed adult who isn’t happy where he landed.

AC There’s a lot of Korean fried chicken in this book.

CQKorean fried chicken was my comfort food for a long time. My characters eat it when they need comfort. It was deliberate. The copy editor at Tin House flagged it after reading “Chicken. Film. Youth.” and “Zeroes: Ones,” both of which feature the characters eating fried chicken. She asked, “Why is she eating fried chicken again? Can it be a different food?” And I wrote back, “No. It has to be Korean fried chicken because that’s my comfort food.”

AC Sounds like a good edit to push back on.

“Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go” was inspired by a 2019 exhibit at the Japan Society, the conceptual artist Yutaka Matsuzawa, and Group Ultra Niigata (GUN). How did visual art affect that particular story? You’re also in an art and performance collective, Egocircus.

CQ I’m interested in how conceptual visual art can be. Marina Abramović did a piece where she and her ex-lover walked toward one another and broke up on the Great Wall of China. I thought, Wow, that’s art? That’s a cool concept. So much non-literary art can be based on just an idea of, What if?

Egocircus is essentially a Zoom group of writers that gossips weekly. It was like “show and tell.” We made silly things like collages and “Poetry Films” with no actors or plot. I made one by pirating old film clips from an online Japanese archive, then splicing the clips together. I wrote a talk chat over it, and it was all about women disappearing.

AC Writing is a ghostly form. You’re not in your body. You’re typing. And performance art especially is about being in your body, being in the moment, improvising.

CQ My stories are often about characters who feel disembodied, which I also feel. I didn’t realize that until I started doing yoga and the other physical activities I mentioned. We’re glued to our phones. I write and read a lot, which is also all in my head. I have friends who are cerebral and intellectual and so fun to talk to, but we’re not very connected to our bodies. That’s unnatural. We should all be more in touch with our bodies.

AC In “We Were There,” Luna says: “I didn’t like to talk about being Chinese or Chinese American. I thought it was safer to keep my experience to myself, unvoiced.” The existence of the story indicates that the character has ultimately decided not to keep her experiences to herself.

CQ But the story isn’t about being Chinese American. It’s about a summer romance. What Luna says comes from me feeling annoyed at the expectation that I, as a Chinese American, might have some thoughts on being Chinese American. I do. But I don’t think they have to inform my fiction.

This goes back to the pigeonholing and the whiteness in publishing. It feels like if you’re a Chinese American writer, you ought to write about what it’s like to be Chinese American. I wanted the right to not write about that. My Chinese American friends and I do not go around living uniquely Chinese American lives. We’re just out here getting ghosted, getting tacos, playing pick-up soccer, debating the ethics of eating meat in an environmentally catastrophic time. If I have 10,000 thoughts in a day, most of those thoughts are not about the condition of being Chinese American.

If I say my experience was one way, so many other Asian Americans would be like, I don’t agree with that. There’s no point, I don’t want to speak for everyone else and I shouldn’t. There’s pressure on many Asian and POC writers to be spokespeople for this huge population of vastly different temperaments and ideologies.

Yet in the stories, Luna is grappling with different parts of her Asianness. Part of her attraction to the character in “We Were There” is his take on being Chinese, and that feeling of familiarity that she has with him.

AC What else came up in the editing process?

CQ “Messages from Earth” changed a lot. I wrestled with including it at all.

AC Why?

CQ Because it’s a very Chinese American story. Similar to what Luna said, I didn’t want this collection to be like, Stories About the Chinese American Experience, because that’s not what it is. I worried that including that story would pigeonhole me as an “immigrant experience” writer.

AC To me, it relates to these broader ideas of female friendships, or women one might look towards in the process of growing up.

CQ That story shows Luna at her youngest. The reader sees that she’s come so far between her childhood and her twenty-something self in “Chicken. Film. Youth.” In “Messages from Earth,” she’s still very idealistic. She encounters adult troubles and disappointments for the first time and begins the questioning that dogs her for the rest of her adult life. There are lines in that story like, “There would be no final answer to anything…. Constantly, they were in the process of becoming.” Someone quoted it on Tumblr, and I was once a real Tumblr girlie. I thought, Oh my god, the young ones are finding guidance in this paragraph.