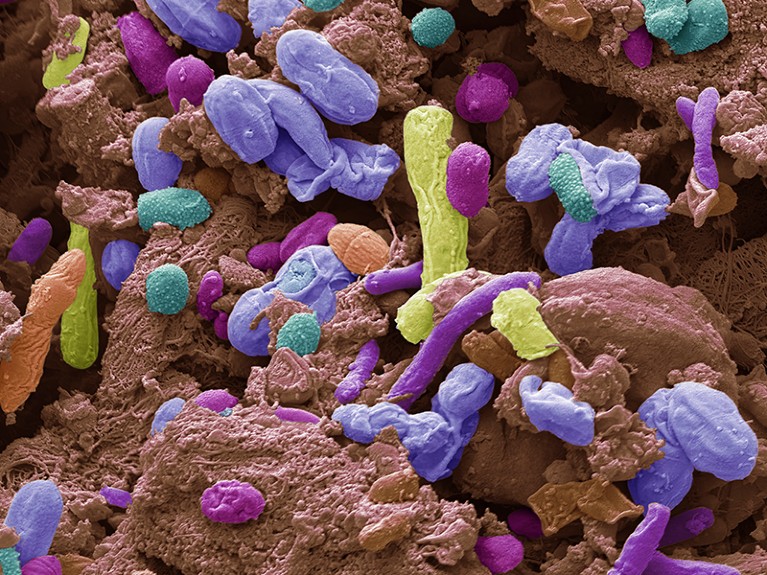

Changes in the make-up of microorganisms in the gut have been linked to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/SPL

For decades, scientists thought of the brain as the body’s most valuable — and consequently most closely guarded — asset. Locked safely behind a biological barrier, away from the hurly-burly of the rest of the body, it was broadly free of the ravages of invading germs, the battles waged by the immune system and the constant churn of cells.

Then, 20-odd years ago, some researchers began to ask a heretical question: is the brain really so isolated? The answer, according to a growing body of evidence, is no — and has important implications for both science and health care.

The list of brain conditions that have been associated with changes elsewhere in the body is long and growing. Changes in the make-up of the microorganisms resident in the gut, for example, have been linked to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and motor neuron disease. Some researchers think that certain infections could provoke the onset of Alzheimer’s disease; there is also a theory that infection during pregnancy could lead to autism spectrum disorder in babies.

Your brain could be controlling how sick you get — and how you recover

The effect is two-way. There is a lengthening list of symptoms not typically viewed as disorders of the nervous system in which the brain and the neural processes that connect it to the body play a large part. For example, the development of a fever is influenced by a population of neurons that control body temperature and appetite. The effect of brain on body is underlined by the finding that stimulating a particular brain region in mice can ‘remind’ the body of previous bouts of inflammation — and reproduce them1.

The list goes on. Evidence is mounting that cancers use nerves to grow and spread. In this week’s Nature, Michelle Monje and her colleagues2 show how some brain cancers consolidate connections with neurons that enhance their progression. Meanwhile, Jonathan Lovelace and his colleagues3 explore the neural pathway that can cause a drop in blood pressure and fainting. This comprises a group of nerves that project from the heart to the brainstem.

These findings and others mark a radical shift in our view of the nervous system, and neuroscientists are still only beginning to explore its impacts. To really get to grips with how the brain and the body are entangled, researchers in a range of fields will need to work together more closely. Ultimately, the goal should be to study the interplay between the brain and body in humans. This will require methods for accessing brain function, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, as Emily Finn and her colleagues4 describe in a Perspective article.

Guardians of the brain: how a special immune system protects our grey matter

The interconnectedness of brain and body has tantalizing implications for our ability to both understand and treat illness. If some brain conditions start outside the brain, then perhaps therapies for them could also reach in from outside. Treatments that take effect through the digestive system, heart or other organs, for instance, would be much easier and less invasive to administer than those that must cross the blood–brain barrier, the brain’s first line of defence against pathogens and other insults from the body.

In the reverse direction, the effects of our emotions or mood on our capacity to recover from illness could also be exploited. There is, for instance, preliminary work under way testing whether stimulating certain areas of the brain that respond to reward and produce feelings of positivity could enhance recovery from conditions such as heart attacks. Perhaps even more exciting is the possibility that making changes to our behaviour — to reduce stress, say — could have similar benefits.

For neuroscientists, it’s time to look beyond the brain. And clinicians treating the body mustn’t assume the brain is above getting involved — its activity could be influencing a wide range of conditions, from mild infections to chronic obesity.