GLOUCESTER – “Fish City Studios” reads the blocky, black-stenciled text in the narrow storefront window on Gloucesters Main Street, a visual anchor awash in vibrant stains of paint and ink. For the better part of a decade, the artist Jon Sarkin worked here. Up the half-dozen stairs and into the slender space, you’d find him at his drawing table tucked in the back corner, all day, every day, churning out some 15,000 pieces over the years.

Sarkin died suddenly last summer at that table, pen in hand; he was 71. When they found him, his studio manager Mark Henderson told me, “he looked so peaceful, like he had just dozed off.” He died as he had lived — drawing, always drawing, a compulsion that soothed the trauma of a severe brain injury more than 30 years before. But his work — mountains and mountains of it, a monument to the relief it gave him — isn’t about therapy, or even pain. It’s about a man whose mind was remade in an instant working his way back, furiously, joyously, to himself.

Henderson and Sarkin’s family — his wife, Kim, and his three children, Curtis, Robin, and Caroline — opened a memorial exhibition at the Cape Ann Community Cinema in Rockport in the fall; it runs through the end of March. Sarkin, a folk hero in the Gloucester art scene, deserves no less, and two rooms chock-full of his work make a lovely tribute, though they’re an inevitably slim sampling of his prodigious output. You won’t find Sarkin’s work in any museums around here, relegated as it is to the vast and ramshackle category art institutions have long diminished as “outsider” art — rough, raw work by the untrained and self-taught. But among its outsider art’s aficionados, and they are legion, he’s a legend.

As the art world has become more porous in recent years, though, so-called outsiders are starting to find a place in a pantheon that has excluded them for years. And since Sarkin’s passing, Henderson tells me, curators have come calling; without naming names, he says he’s meeting with some in the coming weeks.

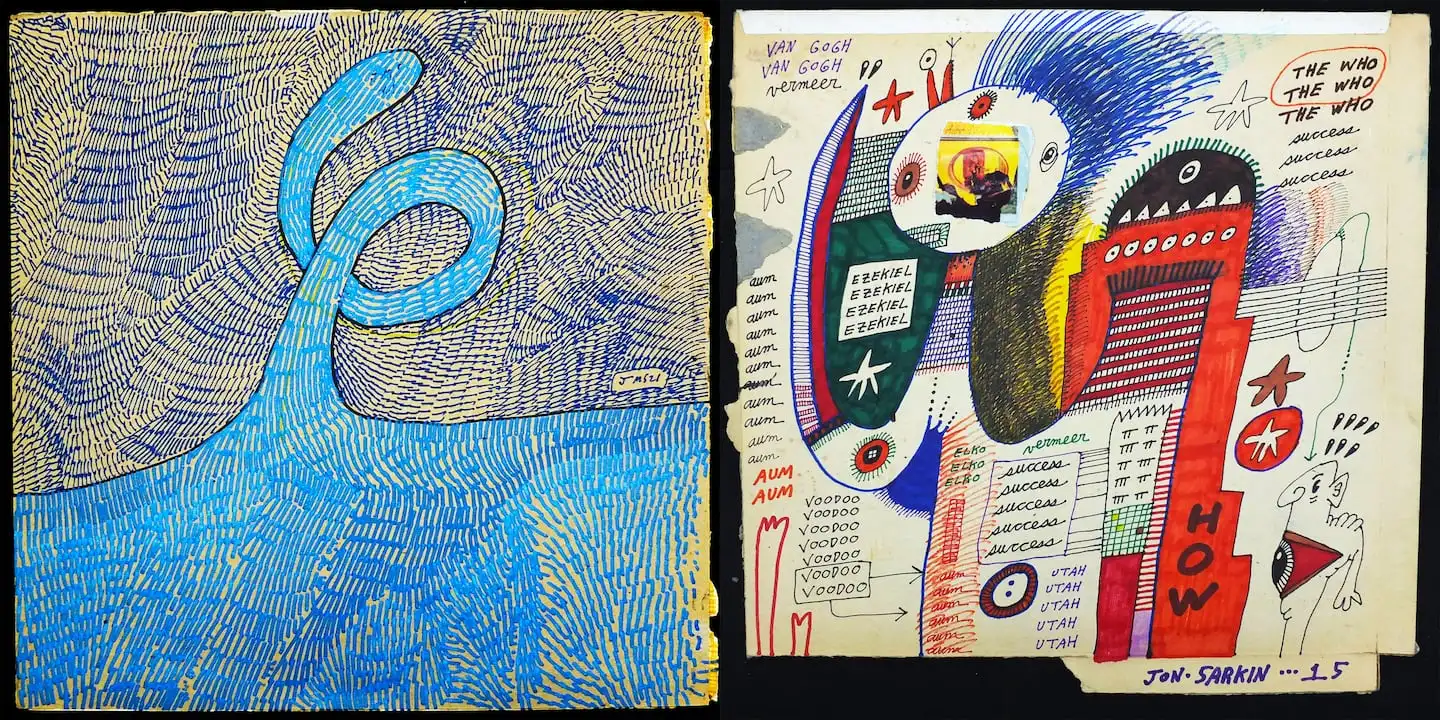

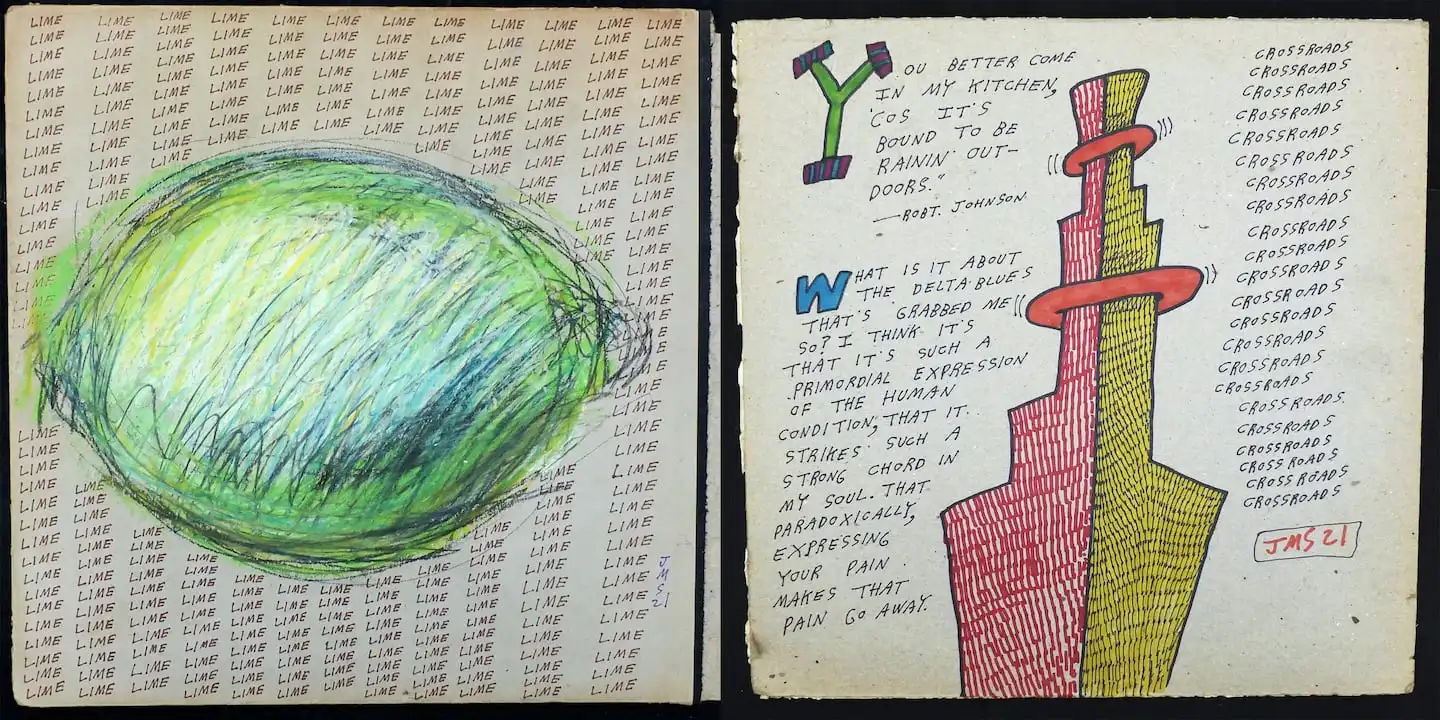

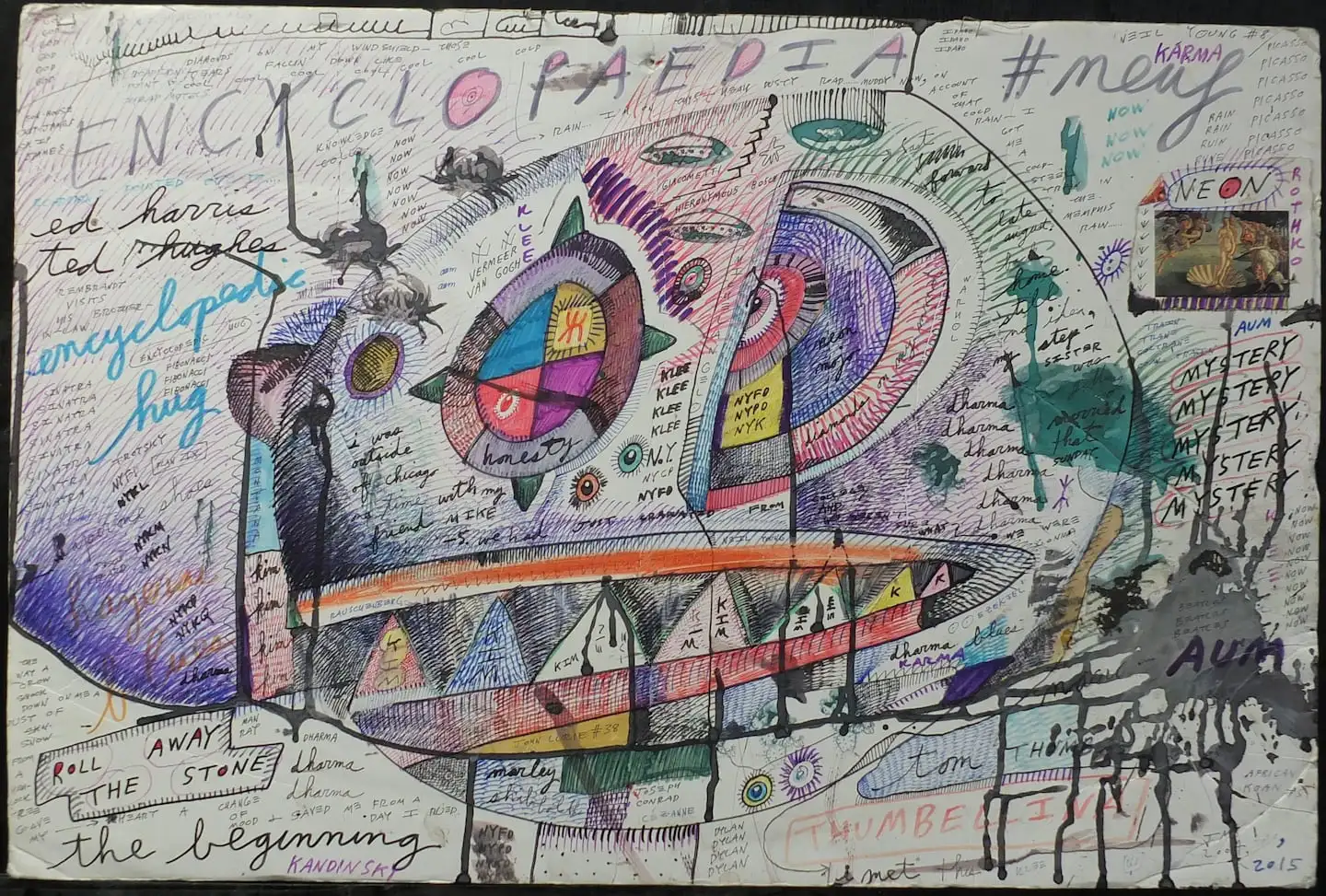

Sarkin’s work ranges from stark pen and ink drawing to vibrant large-scale canvases and oil stick compositions that simmer with a soft, manic energy. But his ink drawings, packed with patterns of text in his distinctly scratchy hand-printing, are his signature. They’re often dizzying, stream-of-consciousness journeys arranged and composed by an intuitive logic.

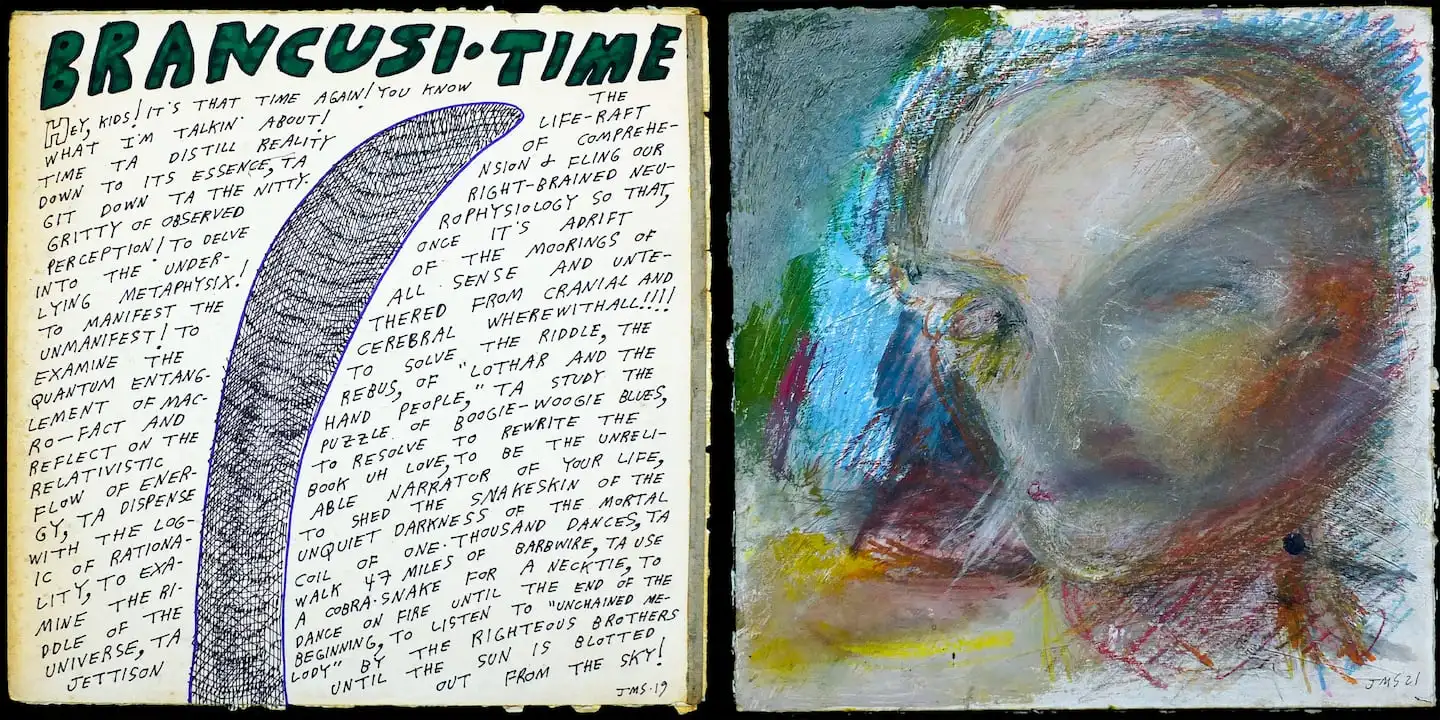

Frenzied, comic, and frequently profound, they swim with visitations from his broad cultural fluency. Sarkin quotes Bob Dylan, namechecks Rachmaninoff, Verdi, Joni Mitchell, and John Coltrane, or invokes Picasso, Klee, Bosch, and Vermeer, in blizzards of text. Yeats, Rauschenberg, and Hunter S. Thompson are recurring favorites; so is Brancusi, a master of Modernism at its most minimal and austere.

Look closely at a 6-foot-wide mixed-media composition and you can extract Seamus Heaney, Walker Percy, and W.B. Yeats. Robert Johnson, the Delta blues icon, appears again and again, often in a starring role. His was a parable Sarkin savored: Johnson, the story goes, sold his soul to the devil for the gift of supreme talent.

With his cartoonishly ghoulish figures, Sarkin is natural aesthetic kin with the underground comics virtuoso Robert Crumb, of whom he was a fan. (The show in Rockport features a smattering of his “superhero” drawings: “The Human Fork” and “Cardboard Man.”) More than a few of Sarkin’s drawings are visceral psychedelia, distorted figures carved in sharp, brisk strokes — a mouth elongated in the long curl of a grin that cleaves through the back of the head, or a Picasso-esque nose, folded inward against the face.

His obsessive, repetitive word play, clustered in masses or floating in chaotic tableaux of color and image, can be charged with conspiratorial whispers that remind me of Mark Lombardi, whose spiraling networks of hand-scrawled text intimated corruption at the highest levels of government. It’s also not hard to see echoes of Jean-Michel Basquiat in the wild collision of image and text that Sarkin routinely composed.

But his work is shot through with such good humor, powerful and authentic, that it’s impossible not to be charmed. (“BRANCUSI-TIME” reads one drawing in big green block letters, with a long, oblong form arcing against a field of text; “Hey kids!” Sarkin wrote; “it’s time ta distill reality down to its essence, time ta get down to the nitty gritty of observed perception!”)

Sarkin drew compulsively, not as a traumatized savant, but with urgent purpose. In 1988, he was a Cape Ann chiropractor, married with a baby son, Curtis, at home. Playing a round of golf one sunny day, he reached down to pick up a ball and was struck with a crippling ringing in his ears. Complications from surgery to correct severe tinnitus led to a massive stroke. His brain started bleeding and he was rushed back to emergency surgery, where his heart stopped twice, starving his brain of oxygen, requiring part of his cerebellum to be removed.

When he finally woke, he was all but a stranger to himself. He had lost a significant part of his left brain, responsible for routine function and linear thinking. The right had to compensate; its natural role, generating intuitive, instinctual, novel, and immediate thought, created a new world for Sarkin to negotiate. Art became a way for him to reorder his new reality, but practically, it was also a refuge from his brain’s betrayal. The stroke had left him with seasick-like nausea; only drawing would quell it.

In 2011, Amy Ellis Nutt published “Shadows Bright as Glass,” a book about Sarkin’s transformation. Sarkin and Nutt went on NPR’s “Fresh Air“ with Terry Gross that year, where he explained that his art was “a manifestation of what happened to me. … I’ve learned how to visually represent my existential dilemma caused by my stroke.”

When I dropped by the Main Street studio in the fall, Henderson was almost literally knee-deep in Sarkin’s work. Square drawings made on the blank interiors of record jackets were piled high on a table; double as many were stacked on floor-to-ceiling shelving near the front window (Mystery Train, a vintage record shop a few doors down, was an inexhaustible resource; Sarkin loaded up on records from the freebie shelves. Towers of abandoned vinyl were routinely stacked all around the studio.) Henderson led me to a back room, where huge unstretched canvases sat loosely rolled against walls. Works on paper, jumbled together in thickets, spilled from tall shelves. When I noted he was standing on several pieces, he shrugged. “Jon really wouldn’t mind,” he said.

Henderson and Sarkin first met in 2006. Henderson was an independent ‘zine publisher, hoping to put together a show of Sarkin’s work. Sarkin invited him to the studio with a caveat: that he would choose works at random from the surrounding piles, and Henderson would simply say yes or no — no deliberation, no explanation. The no’s, Henderson recalled, Sarkin would throw across the room and leave where they fell. Shocked, Henderson asked if he wasn’t worried about ruining them. Sarkin smiled, Henderson recalled. “He said, ‘I’ll just make more.’”

Early in the new year, I dropped in to see Henderson at the studio again. He and Sarkin’s family plan to hold onto the space for as long as they can, a tribute to him and a toehold in the community he loved. The studio “was like a barbershop,” Henderson said, with constant comings and goings. Henderson sets up at Sarkin’s old drawing table, keeping the door open as many days as he can, entertaining the curious, communing with old friends, and selling pieces as he’s able.

The studio has been tidied, but elements of Sarkin’s perpetual chaos remain. Above the drawing table is an arc of a dozen or more ghostly oil stick portraits of Judith, the biblical slayer of Holofernes, a subject Sarkin returned to over and over. (The story was a staple of Renaissance painting, perhaps most famously by Artemisia Gentileschi.) The mountains of drawings are gone, replaced with a small, neat stack and a display case for easy leafing. A modest pile of records sits on the floor, an homage to past mess; but the floor, lacquered with paint, ink, and who knows what else, is untouched.

It feels like what it is: a once-living space with its animating force now gone. I don’t know what Sarkin’s legacy will be, and how — or if — it will be preserved, though his reputation in the outsider art world is towering. (Henderson told me he once asked him what would happen to his art when he died; “That’s an easy one,” Sarkin answered. “I don’t care!”)

What I do know is that once I start looking at Sarkin’s work, I can’t stop; it’s a bottomless pit of fascination, a creative intellect powered by humor, joy, and love (amid the tangle of cultural references, philosophy, and potboiler storytelling, maybe the most oft-repeated phrase in his work was, simply, “May you be happy.”)

I don’t look at Sarkin’s work as the product of tragedy, or romanticize it as clarity achieved through trauma. Maybe it’s best to look at it — all of it — as he did. “I have been in a state of amusement for over 30 years,” Sarkin says, in a video at the exhibition in Rockport, “and I can’t believe that this is what I do now.”

JON SARKIN: SUPERARTIST

Through March 31. Cape Ann Community Cinema, 37 Whistlestop Mall, Rockport. 978-226-3800, www.capeanncinema.com

Fish City Studios, 39 Main St., Gloucester. Open most days. www.jonsarkin.com

Murray Whyte can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him @TheMurrayWhyte.