Changing climate patterns and growing populations are having an impact on all of our lives, but it is also affecting birds and their migration patterns.

Migratory birds benefit from the changing seasons, but with hotter summers and colder winters, along with disappearing habitats, some species are struggling to keep up.

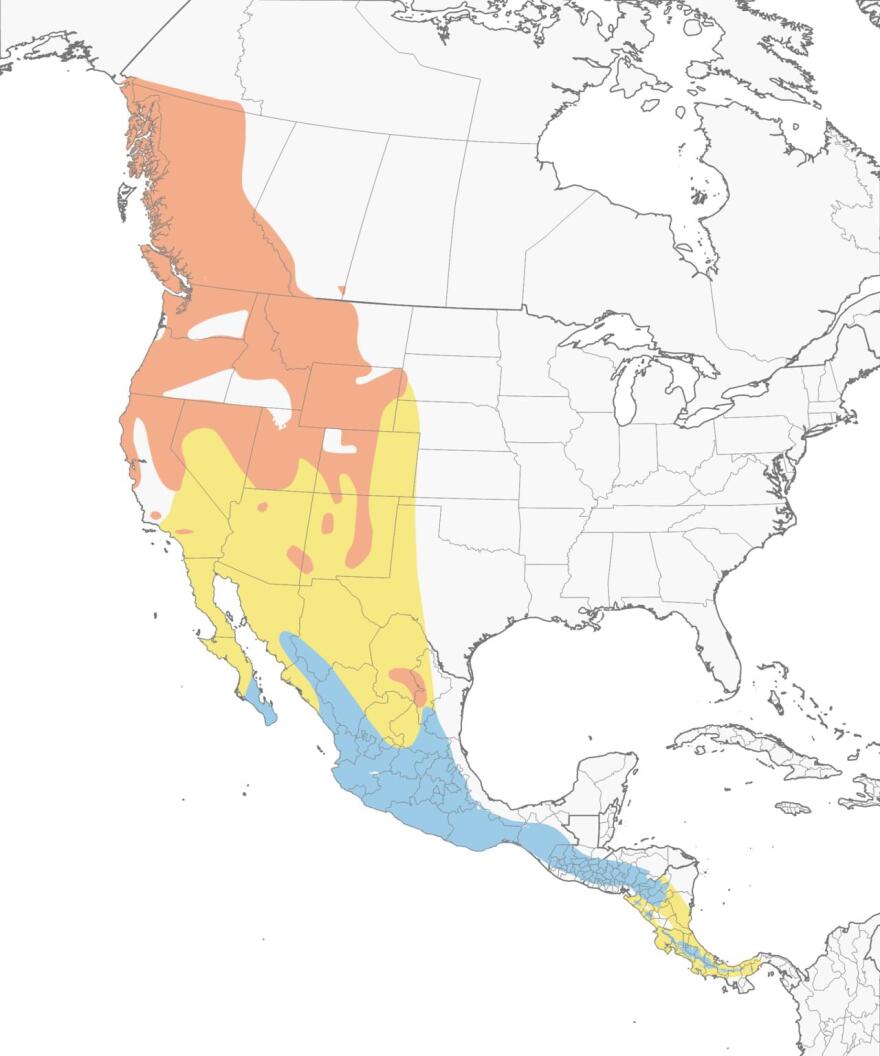

The MacGillivray’s Warbler is a small bird that has its breeding ground in most of Idaho, the Pacific Northwest and stretching up into Canada. In early fall, the warbler makes its way down to Mexico and parts of Central America for the winter.

All About Birds

“They should be fueling up, getting fatter and fatter to kind of fuel that gas tank,” said Heidi Ware-Carlisle, the education director at the Intermountain Bird Observatory. The IBO conducts breeding season and migration songbird monitoring and banding at the Diane Moore Nature Center near Lucky Peak each year.

Ware-Carlisle studied how road noise affects the warbler and other birds. As part of a team of researchers, they found over a one-quarter decline in bird abundance and almost complete avoidance by some species during the fall migratory period at an established stopover site in southern Idaho.

“For example, MacGillivray’s Warblers didn’t change in number when we were playing a bunch of road noise or whether it was beautiful, pristine, quiet. But when there was road noise, they did terribly on migration.”

There are a lot of reasons why bird migration is being affected by humans, ranging from road noise, habitat loss and light pollution. But the data on how those are affecting the birds aren’t very clear, but we are seeing birds migrating earlier.

“You see a bigger spread in terms of the timing of leaving the breeding grounds and going back to the wintering grounds,” said Brian Weeks, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability. “And there’s some variation in that around the world. So you see birds advancing the timing of their migration by two or three days every decade.”

Warning signs

Scientists aren’t seeing a huge shift in migration related to climate change yet, but they say the warning signs are there.

“Even as the world warms a little bit, you don’t see any major switches from migratory behavior to non-migratory behavior,” said Weeks. “They’re not even close to being able to overwinter in Boise. They have to make these migrations or they’ll all die over the winter.”

When thinking about conservation, some species are going to do alright. But with species already impacted by diminishing habitats, they are going to face more challenges.

“Whether or not species are going to be able to continue to advance the timing of their migration while also dealing with the fact that they are shrinking is a really open question that we just can’t answer,” said Weeks.

However, birds are slowly adapting to climate change. Besides migrating earlier and shifting habitats, we’re also seeing longer wingspans and other physiological changes. But will their adaptations be enough and what does that mean for humans?

“You should think of birds as, you know, the canaries in the coal mine. They’re reflecting our general impact on natural systems, and they’re declining because we are reducing the extent and quality of natural habitats.”

Brian Weeks

But at some point, birds will run out of space to move. Chris McClure with the Peregrine Fund in Boise says birds will be driven more and more to the Earth’s poles, but birds already there can’t go anywhere.

Katie Kloppenburg

/

Boise State Public Radio

“They’re already at the end of the Earth, basically. Some species we have quantitatively shown will run out of habitat, or have less habitat then they are used to,” said McClure.

What humans can do

With all this happening, what can you do to help? For noise pollution, you can pick bikes over cars, plant more trees as noise buffers and maintain your vehicle if you must drive.

“People don’t like noise pollution either, so it’s a little bit of an easier sell,” said Ware-Carlisle. “Think you’re going like hey, in these protected areas, can we do something? It’s going to benefit wildlife and it’s going to benefit human enjoyment.”

Controlling light pollution can also go a long way.

“I think if you’re looking for actions, the things that can be done are lights out programs in big urban areas. There needs to be some sort of critical mass of light to attract birds into these buildings,” said Weeks.

Civic engagement can also go a long way when it comes to birds and other forms of wildlife.

“I’m not going to say who to vote for or anything,” said McClure, “but if you care about conservation, at least vote for science-based candidates that respect the process of science and are willing to follow the facts.”

As the world warms and habitat transforms, birds can show us how making it a better place for them will also make it a better place for us.