From the city’s inception, neither entertainment nor the arts have been at the center of Longview’s industry or creative focus. Frankly, there wouldn’t be any reason for them to be; from the start, Longview has been arguably the foremost manufacturing hub in southwest Washington. From lumber to metals to recycling, the heart and soul of this city has been its industrial sector. As such, the history of entertainment in this city has evolved as a reflection of its times and economic circumstances. From the city’s early days of economic promise and grand spending of the interwar period to the impact of the eruption of Mount St. Helens, Longview’s recreation has reflected the economic and environmental state of the city in ways that few cities do.

The early years, 1923-1945

In its early days, entertainment and recreation in Longview seemed to be centered around two focal points: the Columbia Theatre and the YMCA. The oldest center for recreation in the city is a title that belongs to the Y, which was established in January of 1923 at a temporary facility located around the 500 block of Oregon way, according to the YMCA of SW Washington’s website.

People are also reading…

The Y was a hub for socialization, recreation and relaxation. For a time, it even showed silent films featuring actors like Charlie Chaplin, Mark Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., according to the site. Though the operations at the original site were wildly successful, it soon became clear that the Y required more space. The old facility shared a building with the post office, and a general store. With all the traffic generated by the YMCA, it clearly needed a home to itself. Once the necessity of a more permanent center emerged, construction began on a new center for the YMCA. It was built at 15th and Douglas, and it opened on Dec. 17, 1923.

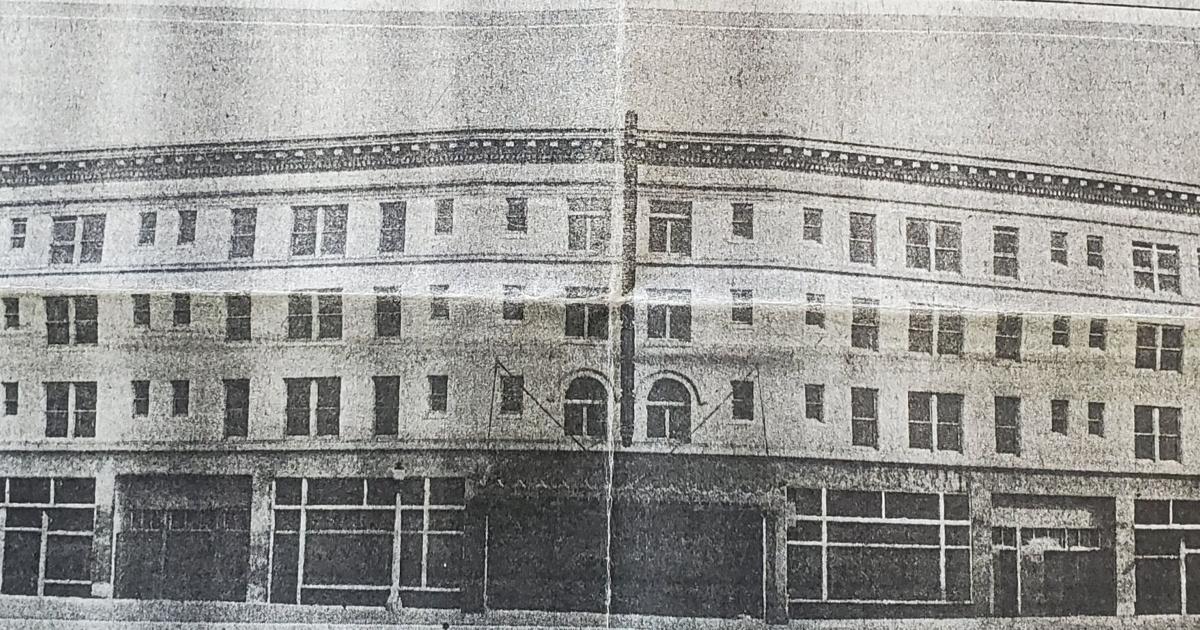

More than two full years after the YMCA came to life, arguably the most iconic attraction in the city was opened. The Columbia Theatre, known for its distinctive exterior and elaborate interior, opened its doors for the first time on April 3,1925. It was received with near-universal fanfare and several pages of print in TDN’s edition from that day. Stories marveled at its ventilation, steel construction, detailed decoration,

In its younger years, the Columbia housed vaudeville shows and other live performances with the occasional intermixing of silent films. From the very beginning, the theater had trouble balancing its finances. Apparently unable to draw crowds to recoup costs of its 250,000 construction and maintenance, the theater declared bankruptcy and was sold in 1935, according to the theater’s managing director, Kelly Ragsdale. The theater was sold to a loan company in Tacoma before it was picked up by movie theater chain SRO toward the end of the decade, and the city’s vaudeville days were gone – at least for now.

The postwar period, 1945-1980

As Longview’s economy shifted away from lumber and towards metalworking, so too did local recreation evolve. Recreation in the 1950s and ‘60s were marked by nationwide fads that were accentuated by local flair, especially the local car and cruising scene. For those unfamiliar, cruising was a trend in the mid-to-late 20th century that involved large groups of people – usually high school-aged kids – slowly driving around town in large groups and using the time to socialize.

During a period when the American economy boomed, so too did Longview’s. People of the time, like Tony Fardell — who attended R.A. Long High School together and graduated a couple of years apart in the 1960s — recall an era when jobs were plentiful, paid a living wage and school was achievable.

“We had lots of guys that went to work and lots of guys that had the GI Bill. LCC always had a big automotive and welding school,” Fardell said. “A lot of guys thought, ‘my GI Bill is just going to go to waste if I don’t do something,’ so they took automotive, auto welding or auto mechanics.”

He said he believes this pattern led to the development of a popular local hot rod and cruising scene that was central to teenage recreation in the 1960s and 1970s. Jim Zonich, who attended R.A. Long at the same time as Fardell and graduated a couple of years earlier, added that economic opportunity for teenagers was also a significant influence.

“The other thing is that a lot of kids worked at the mills in the summer, so they had some money to be able to buy cars,” Zonich said. Cruising’s social importance extended to other cliques, too; Jim Elliott, a 76-year-old R.A. Long graduate who wasn’t one for traditional recreation like hunting or fishing, also remembers cruising fondly.

“You almost have to explain it today, because why would you get in your car and use up all that gasoline?” Elliott said. Its role, he emphasized, was similar to social media in the present day. It was “a way of keeping in touch with your friends,” and allowed you to catch up on others who may not have even been cruising with you that weekend.

In early life, before kids were old enough to cruise, the outdoors provided plentiful entertainment. Spirit Lake, near Mount St. Helens, was a popular site outside the city, but football and baseball in the park were also local favorites. Zonich, Fardell and others remember raising Cain near Elks Memorial Park.

“We used to play across from Elks Memorial park at the church there before they had paved it, because on Thanksgiving day, we would get home, just covered in mud from playing football,” Zonich said. “And we also played baseball there, until a gentleman by the name of Tom Noble hit a home run and broke the front window of Inman’s house.”

Fardell recalled a similar story. “The pastor came out one day, and goes, ‘you can play,’ because we were playing in the opposite corner of the park,” he said with a smile before chuckling his way into the latter half of his anecdote. “Somebody hit a home run through one of the stained glass windows, and he said, ‘you’re done. By the way, give me your name, you’re paying for the window.’”

It was during this time that the Columbia’s age and financial woes caught up to it again. Through the 1960s and ‘70s, it became clear that the theater needed significant renovations to stay open. Though it had less trouble attracting audiences for movies than it did before with live shows, profits proved insufficient for SRO to keep the theater open. Renovations were too costly, and as a result, the theater fell into a state of disrepair toward the end of the decade. The historic Columbia Theater was set to be torn down in 1980, around the same time that cruising fell out of favor nationally and shortly before Spirit Lake recreation changed forever. It looked like the end of an era in more ways than one.

But, as most anyone in Longview today could tell you, the Columbia was not, in fact, torn down. Many people familiar with the history credit an unlikely savior: The Pacific Northwest’s most famous volcano.

Present day, 1980-2023

“Nothing in my lifetime changed the way things were around here like that eruption,” Jim Elliott said in his living room between bites of homemade chocolate chip cookies.

Elliott, like many others, credits the eruption of Mount St. Helens for the survival of the Columbia Theatre. Depending on who you ask, the story comes in slightly different forms. Some say that the demolition crews were in place on site and waiting for the final order when the mountain blew, forcing the city to reallocate its resources to focus on cleanup and rescue. The redirection bought the theater valuable time.

A conservation group led by Virginia Rubin took advantage of the last-minute shift and convinced the city to swap a parcel of land elsewhere in town with the development company and allow management of the theater to be entrusted to the Columbia Theatre Task Force. Over the next 30 years, renovations turned the theater from what Elliott once called a “fire trap” into what it is today: A remarkably well-preserved testament to the power of collective action with a little help from Lady Luck.

Despite the positive impact Mount St. Helens had on the Columbia, it had devastating effects on its local ecology. It decimated homes, campsites, forests and a full summer’s outdoor activities. Many of the landmarks so fondly remembered by Zonich, Elliott, Fardell and others were swept away in pyroclastic flows or buried under ash and debris. Recreation on and around the mountain has returned to a degree but is mostly restricted to hikers and climbers.

Cruising eventually fell out of favor in Longview and across the nation due to increasing association with violence, drugs and alcohol. Now, much like the rest of the country, casual youth entertainment is more often indoors or online, Elliott says

Longview’s recreational scene has reflected the times in ways that a big city’s wouldn’t. A desire for growth and R.A. Long’s vision built the Columbia, and economic struggle from the loss of manufacturing and lumber nearly killed it, but much like this city, it has persisted thanks to — or often in spite of — its financial and environmental circumstances.

#lee-rev-content { margin:0 -5px; }

#lee-rev-content h3 {

font-family: inherit!important;

font-weight: 700!important;

border-left: 8px solid var(–lee-blox-link-color);

text-indent: 7px;

font-size: 24px!important;

line-height: 24px;

}

#lee-rev-content .rc-provider {

font-family: inherit!important;

}

#lee-rev-content h4 {

line-height: 24px!important;

font-family: “serif-ds”,Times,”Times New Roman”,serif!important;

margin-top: 10px!important;

}

@media (max-width: 991px) {

#lee-rev-content h3 {

font-size: 18px!important;

line-height: 18px;

}

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article {

clear: both;

background-color: #fff;

color: #222;

background-position: bottom;

background-repeat: no-repeat;

padding: 15px 0 20px;

margin-bottom: 40px;

border-top: 4px solid rgba(0,0,0,.8);

border-bottom: 1px solid rgba(0,0,0,.2);

display: none;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article,

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article p {

font-family: -apple-system, BlinkMacSystemFont, “Segoe UI”, Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif, “Apple Color Emoji”, “Segoe UI Emoji”, “Segoe UI Symbol”;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article h2 {

font-size: 24px;

margin: 15px 0 5px 0;

font-family: “serif-ds”, Times, “Times New Roman”, serif;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article .lead {

margin-bottom: 5px;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article .email-desc {

font-size: 16px;

line-height: 20px;

margin-bottom: 5px;

opacity: 0.7;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article form {

padding: 10px 30px 5px 30px;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article .disclaimer {

opacity: 0.5;

margin-bottom: 0;

line-height: 100%;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article .disclaimer a {

color: #222;

text-decoration: underline;

}

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article .email-hammer {

border-bottom: 3px solid #222;

opacity: .5;

display: inline-block;

padding: 0 10px 5px 10px;

margin-bottom: -5px;

font-size: 16px;

}

@media (max-width: 991px) {

#pu-email-form-breaking-email-article form {

padding: 10px 0 5px 0;

}

}

.grecaptcha-badge { visibility: hidden; }