Cores recovered from below the seafloor provide clues to open questions in Earth science. A looming gap in international ocean drilling requires renewed support and urgent action.

Beneath the seafloor lie sediments, sometimes kilometres thick, draped over the oceanic crust. Recording as much as two hundred million years of Earth history, these sediments provide insights into the oceanographic changes that accompanied climatic events in Earth history. They also host subsurface life and hydrothermal networks fuelled by the mantle that shape modern marine biogeochemical systems. The recent decommissioning of the JOIDES Resolution, one of the few ships capable of collecting long sediment cores in the deep ocean, has raised concern for the future of geoscience disciplines that rely on samples from these settings. In this issue, we highlight the scientific legacy of ocean drilling and the argument for continued support for deep-ocean drilling amidst an uncertain future.

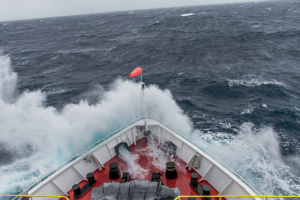

Credit: Thomas Ronge & IODP

The JOIDES Resolution, most recently operated by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), a continuation of collaborative efforts that began in the late 1960s, had been the workhorse of scientific ocean drilling since 1985. Equipped with sophisticated coring equipment able to drill hundreds of metres into a wide variety of sediments and hard rock under thousands of metres of seawater, the ship had developed into a well-equipped floating laboratory. Many kilometres of cores collected during dozens of expeditions have helped answer pressing, and sometimes unexpected, palaeoceanographic, tectonic, and biogeochemical questions1. The ship’s last expedition — aimed at reconstructing ocean circulation through the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard over the past five million years — wrapped up in September of this year. The ship’s decommissioning was the result of a mix of fiscal pressures under increasing operating costs and shifting funder priorities2.

Without a dedicated vessel and no plans for a replacement, it is unclear when and if IODP drilling will recommence. For now, researchers will have to rely on IODP core repositories in Germany, the USA, and Japan that, facilitated by expert curators and support staff, will continue to make archived core material freely available to scientists.

The lack of new records, however, will have detrimental impacts in some fields. In a Correspondence, Daniel Lunt and co-authors discuss the importance of proxy records from deep-sea cores for ground-truthing climate models designed to simulate past climate states. This is especially critical for modelling hothouse climates when atmospheric CO2 exceeded current levels. Unfortunately, there are gaps in the temporal and spatial coverage represented in IODP archives. Additional drilling is required to better constrain models of past climate and improve the fidelity of future projections. Also, as pointed out in a Q&A, for some fields of research, stored cores are insufficient. For example, geomicrobiology research to understand subsurface life in the deep ocean relies on pristine samples. Creative use of legacy samples or targeted expeditions using ships equipped with different or more limited capabilities can help fill research gaps left behind in the wake of the JOIDES Resolution but cannot fully replace a dedicated drilling vessel.

The JOIDES Resolution’s expeditions brought together geoscientists from across the world and fostered international collaboration and innovation. Dustin Harper and co-authors explain in a Correspondence how these expeditions played a seminal role in the careers of early-career researchers. The lack of an active drilling programme may also lead to the loss of support staff and their technical, operational, and scientific expertise.

The broader IODP research community has been working to safeguard scientific ocean drilling, and advocating for a new ship, with arguments including the pressing need to understand future risks associated with sea level rise, evolving natural hazards, and ocean circulation changes3,4. Other ships and national drilling efforts offer hope. For instance, the D/V Chikyū, operated by Japan in collaboration with international partners, is also capable of deep drilling, though it has been optimized for reaching the uppermost mantle5. The China Geological Survey also took delivery in mid-November of a new vessel, the Meng Xiang, capable of a wide range of deep ocean drilling applications, the scientific programme for which is being developed and is open to proposals from international scientists6. There is also potential to expand drilling efforts on land through the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program, as argued in a Correspondence by Jonathan Obrist-Farner and colleagues.

Losing the capability to sample the subsurface where scientific questions are most pressing would be detrimental to the advance of the Earth sciences. With so much more left to discover, urgent investment in the necessary deep-sea drilling infrastructure is worth it.

References

-

Voelker, A. H. L. et al. Achievements of scientific drilling in paleosciences. Past Global Changes Magazine 32, 66–146 (2024).

-

Benningfield, D. There is no JOIDES in mudville. Eos https://eos.org/features/there-is-no-joides-in-mudville (15 November 2023).

-

Koppers, A. A. P. & Coggon, R. (eds) Exploring Earth by Scientific Ocean Drilling: 2050 Science Framework (UC San Diego Library, 2020).

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Progress and Priorities in Ocean Drilling: In Search of Earth’s Past and Future (National Academies Press, 2024).

-

Lissenberg, C. J. et al. Science 385, 623–629 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Tuo, S. & Wang, W. Preparing for international scientific ocean drilling beyond 2024: China’s actions and plans. Past Global Changes Magazine 32, 130 (2024).

Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choppy seas for deep ocean drilling.

Nat. Geosci. 17, 1183 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01616-w

-

Published: 06 December 2024

-

Issue Date: December 2024

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01616-w