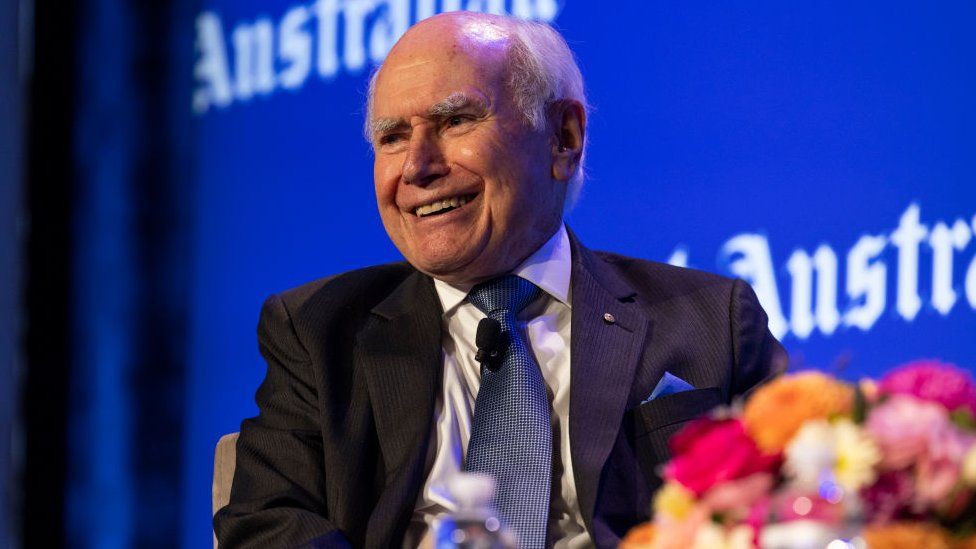

Colonisation was “the luckiest thing that happened” to Australia, the nation’s second-longest serving Prime Minister John Howard has said.

His remarks were made in relation to a historic referendum due to take place this year on Indigenous recognition.

If successful, the vote will change Australia’s constitution to give First Nations peoples a greater say over the laws and policies that affect them.

But the debate has seen a surge of divisive commentary.

Speaking to the Australian Newspaper about the upcoming vote, Mr Howard described colonisation as “inevitable”.

“I do hold the view that the luckiest thing that happened to this country was being colonised by the British,” he said. “Not that they were perfect by any means, but they were infinitely more successful and beneficent colonisers than other European countries.”

He also predicted that the Voice to Parliament initiative would fail to pass, leaving a “new cockpit of conflict” over “how to help Indigenous people” in its wake, while accusing its proponents of failing to sell it to the Australian public.

The Voice vote, Australia’s first referendum since 1999, was announced by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at the start of 2023.

If passed, its supporters say it will lead to better outcomes for Australia’s First Nations people, who face lower life expectancy, and disproportionately poorer health and education outcomes than White Australians.

But those against it argue – among other things – that the Voice is a largely symbolic gesture which will fail to enact reform, while also undermining Australia’s existing government structures.

Recent polling has also shown a steady – yet dramatic – decline in public support for the Voice, as the debate grows more protracted.

Mr Howard is one of the most influential conservative figures to throw his weight behind the No campaign, but his own legacy on Indigenous affairs remains controversial.

His government weakened First Nations land rights, suspended Australia’s racial discrimination act, and refused to apologise to the Stolen Generations – tens of thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were taken from their families by the government until the mid-1960s.

And in 2007 he was the architect of “the Intervention”, a set of policies which saw Australia’s military deployed to seize control of daily life in 73 remote Indigenous communities across the Northern Territory.

The now disbanded scheme – which was enacted following a government report on the sexual abuse of children in Aboriginal communities – has been criticised as “coercive” and culturally insensitive.

Mr Howard defended the policy in his interview on Wednesday as “a good old-fashioned dose of proper governance”.

He also claimed that if the Voice succeeds, it could prevent the government from intervening in Indigenous communities when it is deemed necessary.

Mr Howard’s remarks come amid a wave of controversy that has gripped the referendum’s official No campaign.

This week, one of its leaders faced calls to resign after doubling down on comments that Indigenous Australians should undergo blood tests to prove their lineage, to receive welfare payments.

And earlier this month, the campaign was accused of using a “racist trope” in a newspaper ad, after it paid for a full-page cartoon depicting a prominent Indigenous Voice campaigner dancing for money.

Senior figures within the No camp’s ranks have also been accused of intentionally spreading falsehoods about the vote.

Among them is federal opposition leader Peter Dutton, who warned that the vote would have an “Orwellian effect” on Australian society, by giving First Nations people greater rights and privileges.

It’s a claim that has been further distorted online – and debunked – with social media users suggesting the vote would divide Australians into “settlers” and “original custodians” resulting in a “two-tier government”.

If the Voice referendum passes, it will change the nation’s constitution for the first time in more than 56 years.

Related Topics

- Indigenous Australians