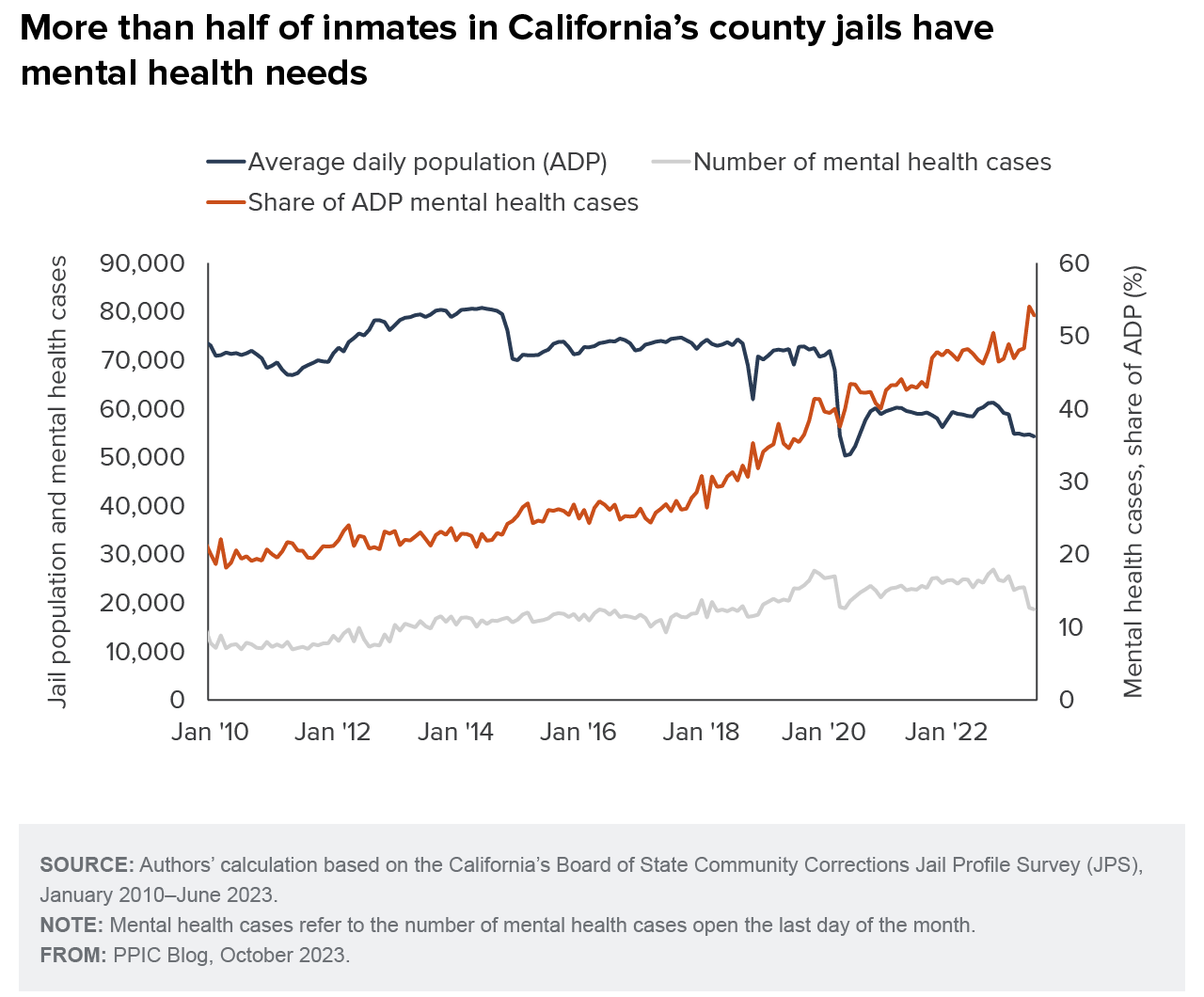

California’s county jail population was trending down before the pandemic but dropped even more during the public health crisis. It is now 24% lower than pre-pandemic levels. However, the number of inmates with mental health needs has increased steadily over the past decade and currently represents more than half of the total jail population. The percentage of inmates held on more serious crimes, especially those awaiting charges and sentencing, has also risen. These shifts highlight some of the challenges that county jails face and the importance of recent efforts to improve access to mental health services.

We examine data on the number of inmates in California’s county jails from January 2010 to June 2023, the most recent month available, provided by the Board of State Community Corrections (BSCC) Jail Profile Survey. The data shows that county jails have been greatly affected by several of the state’s criminal justice reforms and the pandemic.

After realignment in October 2011, which shifted responsibility for lower-level felons from state prison and parole systems to county jail and probation, the average daily population in county jails grew from roughly 69,000 to around 80,000. Then after Proposition 47 in 2014, which reclassified a number of drug and property offenses from felonies (more serious offenses with longer potential sentences) to misdemeanors, the jail population declined and mostly hovered around 71,000–72,000 until the pandemic, when it briefly dropped to 50,000. The county jail population now stands at around 54,000.

While the jail population has dropped markedly over the last decade, the number of inmates with mental health needs has grown, from around 11,000 in the year preceding realignment to 25,000 before the pandemic. The BSCC defines inmates with mental health needs as those who have been identified as having a psychological disorder and who are actively in need of and receiving mental health services.

Following the pandemic-era drop in the overall jail population, the number of inmates with mental health needs also declined and is now around 19,000—still much higher than pre-realignment levels. Additionally, the percentage of inmates with mental health needs has continued to climb, from around 20% in January 2010 to a staggering 53% in June 2023.

Another noteworthy change concerns a shift toward inmates held for more serious crimes. California jails hold both “sentenced” and “nonsentenced” inmates. Sentenced inmates are serving time for misdemeanors and, since realignment, lower-level felonies. Nonsentenced inmates are suspected, arrested, and booked on a crime and are awaiting either arraignment, trial, or sentencing.

The majority of jail inmates have long been nonsentenced and held on a felony offense; this group made up between 55% and 62% of the total jail population for the entire decade before the pandemic. However, since then, even though the number of nonsentenced inmates held on a felony dropped from 43,000 to 38,000, the share has jumped to 70%. Meanwhile, the portion of sentenced felony offenders decreased following Proposition 47 and the pandemic, and is now about 20%, similar to pre-realignment levels. The percentage of inmates being held on a misdemeanor and the share sentenced for a misdemeanor have both declined since 2010, from 20% combined to 10%.

While California has been successful in its goal to decrease its reliance on incarceration, with the combined jail and prison population dropping from about 257,000 at its peak in 2007 to around 151,000 now (a decrease of 41%), our brief analysis shows that in the wake of the state’s criminal justice reforms, those housed in county jails are increasingly in need of mental health care.

This pattern raises questions about jails’ capacity to effectively handle this growing challenge, part of the broader mental health crisis the nation is facing, especially considering that the inmate population has also shifted toward more serious offenders. Monitoring and evaluating recent efforts aimed at addressing mental health and its intersection with homelessness and jails, like the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court and Senate Bill 43, will be essential to determine if these programs successfully deliver effective mental health treatment and support, while reducing reliance on county jails.