Write what you know, they say. A tall order if you’re writing about a serial killer. Most serial killers don’t take the time to sit down and write crime fiction—harder to plot a crime than simply do it, I would think, particularly once you’ve figured it out and are on a roll—but there’s a thought: a serial killer who writes crime novels. Otherwise, you do your research for that part of it.

There are writers who have a great idea, a plot, a construct with a shocking twist, and set it in a generic landscape anywhere. But for me, the most satisfying crime fiction are stories that spring from a particular place and the people who live there; a place and manners the author knows well; stories that could not happen anywhere else.

What I know, in recent years, is the life of a single parent in small town Maine. Being a parent is the sum of all my fears now: that something could happen to my child. Particularly as that child enters the teen years, if he or she has trouble in school and out of school, and you don’t always know where he or she is. And in Maine: Stephen King country; a beautiful rural state of forests and bogs and a rocky coast, full of dark promise.

Here are some novels whose crimes and mysteries grow out of place and manners:

#gallery-1 {

margin: auto;

}

#gallery-1 .gallery-item {

float: left;

margin-top: 10px;

text-align: center;

width: 50%;

}

#gallery-1 img {

border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;

}

#gallery-1 .gallery-caption {

margin-left: 0;

}

/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

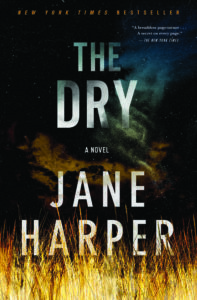

Jane Harper; The Dry, etc; Tana French; In the Woods, etc

Both of theses authors are excellent, well known, and in similar ways have staked out their turf. Jane Harper’s novels are set in Australia, beginning with The Dry, three of them featuring her detective Aaron Falk, others are stand-alone mysteries. Usually involving cold cases—not always murders, sometimes deaths resulting from tragic relationships—Harper’s slow-burn but cinematically rendered stories unwrap layers of Australian communities, family secrets, broken friendships that are defined by landscapes both beautiful and harsh.

Tana French’s stories are set in Ireland. Like Harper, she has a series of novels, The Dublin Murder Squad, beginning with her debut, In The Woods, that feature returning detective characters, with revolving points of view, and stand-alone novels with new characters. Like Harper, her stories are slow-burners: an inciting incident draws the reader in, and the long, deliberate development of her plots is sustained by the convincing details of place, characters, and the quality of French’s writing.

Louise Welsh; The Cutting Room

Less well known, more striking in location and character, is Scottish writer Louise Welsh’s debut novel The Cutting Room. Her protagonist is the grim, saturnine auctioneer, Rilke, who finds snuff porn photographs among the property of a dead man, and sets out to learn the story behind the photos. The photos are almost a MacGuffin for Welsh to take us through Rilke’s world of vividly described alcoholic auctioneers and gay sex hookups in a dismal, gothic Glasgow. Welsh’s writing, characters, and setting of place transcend genre writing into literary fiction. She has authored six crime novels, including most recently a sequel to The Cutting Room, The Second Cut, where we meet Rilke, still alive, 20 years on.

Georges Simenon; , Maigret; Dirty Snow, and the romans durs

The fantastically prolific—over 400 novels—Belgian writer Georges Simenon was most famous for his French police detective Jules Maigret, for whom he wrote 75 novels and 28 short stories—almost double the appearances of Hercule Poirot. Maigret’s world is smoggy, tobacco-filled early to mid-20th century Paris. But Simenon’s greater literary reputation is based on what he called his romans durs—‘hard novels’— “psychological thrillers exploring the darkest corners of the human mind, prostitution, police corruption… the hope of escape represented by railway stations… events which Simenon had experienced and were fictionalized to a criminal or psychological extreme.” Booker Prize-winner John Banville, who writes crime fiction under the pseudonym Benjamin Black, praised Simenon’s novels for their psychological insights and vivid evocation of time and place.

W. Somerset Maugham; The Letter

While not known as a crime writer, during most of his lifetime Maugham was the most famous author in the world. His commercial success so undermined the critical reception of his work that he himself described his position in the literary world as being “in the very first row of the second-raters.” Depending on who’s counting, between 60 and 90 of his novels, plays, and short stories have been adapted to film and TV. One of the most famous of these is his short story, The Letter, the barely fictionalized account of the 1911 murder of a British planter in Malaya by his lover, the wife of another British plantation owner. Its strength is not the nature of the killing but the shame and duplicity and the world of its characters. The Letter became a play, and was filmed twice, best in 1940, starring Bette Davis. The real life murder is also the subject of a 2023 novel, The House of Doors, by Tan Twan Eng, featuring Somerset Maugham as a character. I found it a tepid dilution of Maugham’s original short story, lacking the perfectly drawn time, place, and characters that Maugham knew best.

Edward St Aubyn; The Patrick Melrose books

The five short ‘Patrick Melrose’ novels—Never Mind, Bad News, Some Hope, Mother’s Milk, At Last—by British novelist Edward St Aubyn, are not crime books per se. They are accounts of the emotional and pedophiliac abuse received by St Aubyn’s thinly veiled autobiographical character Patrick Melrose during his childhood at the hands of his parents, dysfunctional British aristocrats, and Patrick’s later adult life. The first book describes Patrick’s rape as a child by his own father at the family’s beautiful chateau in the south of France. Subsequent books deal with Patrick’s life as a drug addict, his father’s funeral, his own attempts at marriage. They are as dark as human familial relations can be, and frequently hysterically funny. St Aubyn is a great prose stylist. His humor is a way to deal with unspeakable abuse and horror. He’s not laughing at his protagonist, with the glee sometimes shown by Stephen King and other authors toward their miscreant creations, St Aubyn is using humor with compassion, as a way to assimilate, for protagonist and reader, the unspeakable. It’s a writing lesson for the ages. HBO made a successful adaptation of the five books, called Patrick Melrose, starring Benedict Cumberbatch. My point here is, again, place and manners. The Melrose books are a trip, a literary benchmark of human misbehavior; guaranteed—trigger warning—to offend every sensibility.

***