We’re always finding ways to capture and learn from the sounds around us: Recordings of melting ice assist in tracking the rate of climate change; hydrophones eavesdropping on underwater insects help measure the health of the ecosystem; and astronomers even figured out the pitch of a massive black hole—B flat, it turned out—in order to investigate how those mysterious nodes grow.

But it wasn’t always this way. To hold up a microphone to our surroundings was once an entirely novel proposition. But in the 1950s, the Folkways label assigned itself the task of documenting the whole world of sound, and sharing it with ordinary listeners. Recording engineer Moses Asch founded Folkways in 1948 as a repository of popular song, spoken word, and folk music from all over the globe. The label is best known for recordings by artists like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, as well as Harry Smith’s monumental Anthology of American Folk Music, but within its first decade, its expanding catalog began to include all manner of non-musical noises: satellites, railroads, summer camp, frogs.

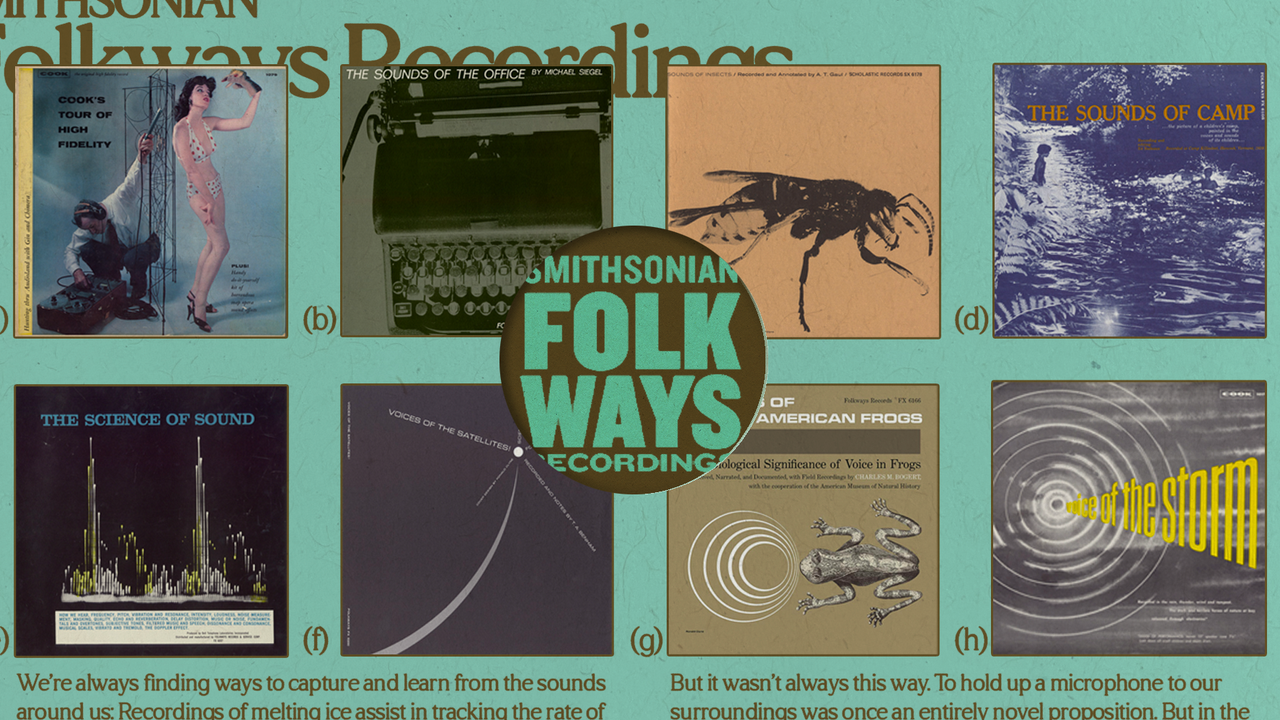

Folkways, which was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1987, celebrates its 75th anniversary this year. To mark the occasion, it commissioned the experimental duo Matmos, who have made a career out of flipping the sounds of cosmetic surgery, riot shields, and washing machines into unusual music, to remix the label’s catalog on non-musical sounds on the new album Return to Archive. To create it, Matmos zeroed in on Folkways’ science, technology, and nature holdings—records like 1955’s Sounds of Medicine, and 1964’s The Sounds of the Office and Speech after the Removal of the Larynx. They even created a track called “Mud-Dauber Wasp” using only the sounds of that titular insect, chopping its whirring into a lurching blast of industrially tinged techno.

From today’s vantage point, some of Folkways’ early, non-musical titles may seem like novelties, and perhaps many of them were at the time. But they also radiate an unmistakable spirit of possibility. Take 1953’s Sound Patterns, an odd compendium that brings together mating tortoises, crickets, human heartbeats, jet planes, African drums, an orchestra tuning up, and even a hot dog vendor. The compilation was intended as the first volume in a run of sonic magazines. “Like photography and art ‘annuals,’” explained the liner notes, “each issue will include the most unusual—and most common—sounds that exist; and through aural interplay, Folkways hopes to be able to establish a mood not unlike that of seeing photographs and pictures.”

It’s hard to imagine sitting down today and willingly pulling up a playlist of such disjointed noises. But part of the beauty of Return to Archive is the way it helps revive that bygone spirit of openness, reminding us how invigorating—and surprising—it can be to listen intently to what’s happening around us.

Here are nine classic recordings from the Smithsonian Folkways catalog that haven’t lost their capacity to captivate overworked ears.

Voice of the Storm (1957)

Before there were white noise apps, there was Emory Cook’s Voice of the Storm. One side is just 25 minutes of rainfall that eventually gives way to chirping crickets; the other captures 16 minutes of thunder and wind recorded, according to the liner notes, “on tempest-torn mountaintops, along the raging edge of the sea, and amid tropical downpours.” The master tapes must have gotten lost at some point, because the version available for download and on streaming services is suffused with the pops and clicks of scuffed vinyl. Throw it on alongside your favorite ambient record and presto: instant Burial.

Sounds of North American Frogs (1958)

Next to birds, frogs might be nature’s most versatile synthesizers. This 1958 album captures the sounds of dozens of species from across North America: spadefoot toads, Mexican leaf frogs, canyon treefrogs, hybrid treefrogs, squirrel treefrogs. In many cases, their names—pig frogs, cricket frogs—indicate what kind of noise to expect.

Across 92 tracks, the sonorous amphibians strike up all manner of din: chirps, croaks, barks, chirrups, beeps, honks, buzzes, squawks, blips, whines, and grunts. (Old MacDonald would have a field day.) The Southern leopard frog could pass for some arcane device from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop; the red-spotted toad’s mating call could be a referee’s whistle. Strangest of all, the Southern toad’s warning vibration sounds like an outtake from an Aphex Twin record.

Over the years, Sounds of North American Frogs has become something of a cult classic. Smithsonian Folkways are reissuing the vinyl as part of their 75th-anniversary campaign; truly committed herpetophiles might want to avail themselves of the campaign’s related merch, like an “I Stop for Frogs” bumper sticker.

Voices of the Satellites (1958)

Everything about this 1958 recording feels like a throwback, from the subject matter to the dated sound of the narrator’s voice. A true Cold War relic, Voices of the Satellites collects recordings made by eavesdropping on Russia’s Sputnik—the first human-made satellite to orbit the earth—as it passed over American soil. On a purely sonic level, the whistling frequencies and crackling static remain captivating more than a half-century later.

The Science of Sound (1958)

There’s an almost-hokey quality to this spoken-word instructional record about acoustic concepts like reverberation, pitch, and dissonance. “Through the ages, man has come to like the sound of certain tones that are played together, or in sequence,” offers the narrator at the outset of a lesson on scales, in that booming tone associated with public service announcements and corporate films from the Cold War era. But it’s precisely that kitschy quality that gives this Bell Telephone Laboratories-produced album its charm—combined with the sorts of meta-musical content that makes it perfectly suited for hip-hop beats and turntablist routines. There’s definitely a nonzero chance that samples from this record might be found in ’90s releases from DJ Shadow and his fellow crate-digging beat miners.

The Sounds of Camp: A Documentary Study of a Children’s Camp (1959)

Where the explanatory voiceovers on some early Folkways recordings can be distracting, 1959’s The Sounds of Camp is nothing but pure, uncut ambience captured on site at Vermont’s Camp Killooleet. To fans of Ernest Hood’s 1975 private-press classic Neighborhoods, or the black-and-white documentary films of Frederick Wiseman, the album’s lo-fi patina is imbued with an unmistakable quotidian warmth. And for anyone who’s been to summer camp, the snippets of woodshop, horse riding, riflery, and campfire will deliver a potent hit of nostalgia.

Sounds of Insects (1960)

This album begins innocuously enough, with the ambient buzz of what’s described as “a typical suburban backyard”; the sounds of kids playing in the background helps set a cozy mood. But things soon get much stranger: Track two takes us inside the body of a hornet, where an electromechanical transducer is used to register the vibrations of the bug’s body as it moves its wings—“much as the insect may sound to itself,” notes narrator Albro T. Gaul. (Spoiler alert: It sounds like a buzzing hornet.)

Gaul’s research treats us to some remarkably diverse sounds, slowing down his raw materials until they resemble the drone of Sunn O))), or the throb of Pan Sonic; his mics are sensitive enough to pick up spiders walking, moths in flight, and even “Japanese beetles on a rose,” as one poetically titled selection details. It’s a feast of extreme sound, nowhere more so than on “Fly caught on flypaper,” which could easily pass for an underground noise record from the early 1980s.

Sounds of the Office (1964)

Since the pandemic, fewer people work regularly in an office than ever, but even those who do probably wouldn’t recognize most of the sounds on this record: time clock, dictation, opening letters, and whatever the hell Thermofaxes, check protectors, and addressographs were.

Cook’s Tour of High Fidelity (1965)

In 1990, the Smithsonian acquired the collection of Cook Records, a label run by recording engineer Emory Cook, and folded it into the Folkways catalog. In addition to Cook’s archive of Japanese koto, New Orleans blues, and Trinidadian music, there were recordings like 1965’s Cook’s Tour of High Fidelity. In addition to the kitschy (albeit sexist) cover, one track alone is worth the price of admission: the 15-minute “Turntableful of Sound Effects, Announcements, and Horrifying Background Moods for the Making of Seductive Soap Operas.”

Sounds and Ultra-Sounds of the Bottle-Nose Dolphin (1973)

Three years after bioacoustician Roger Payne’s Songs of the Humpback Whale popularized the “music” of the majestic endangered sea mammals—his album is credited with helping to save the humpbacks and several other species from extinction—this Folkways release turned its microphones to the bottle-nose dolphin, an animal popularized by aquatic theme parks and the 1960s TV show Flipper. Sounds and Ultra-Sounds of the Bottle-Nose Dolphin features extended passages of fairly mind-blowing gurgles, clicks, and squeals. But where the album really gets wild is in experiments that purport to demonstrate dolphins mimicking human speech; their uncanny vocalizations are half cartoonish and half nightmarish.