A generation ago, farming with animals like lions, rhinos and crocodiles would have seemed bizarre. Today, millions of wild animals are raised on farms to supply a burgeoning demand for pets, parts and meat.

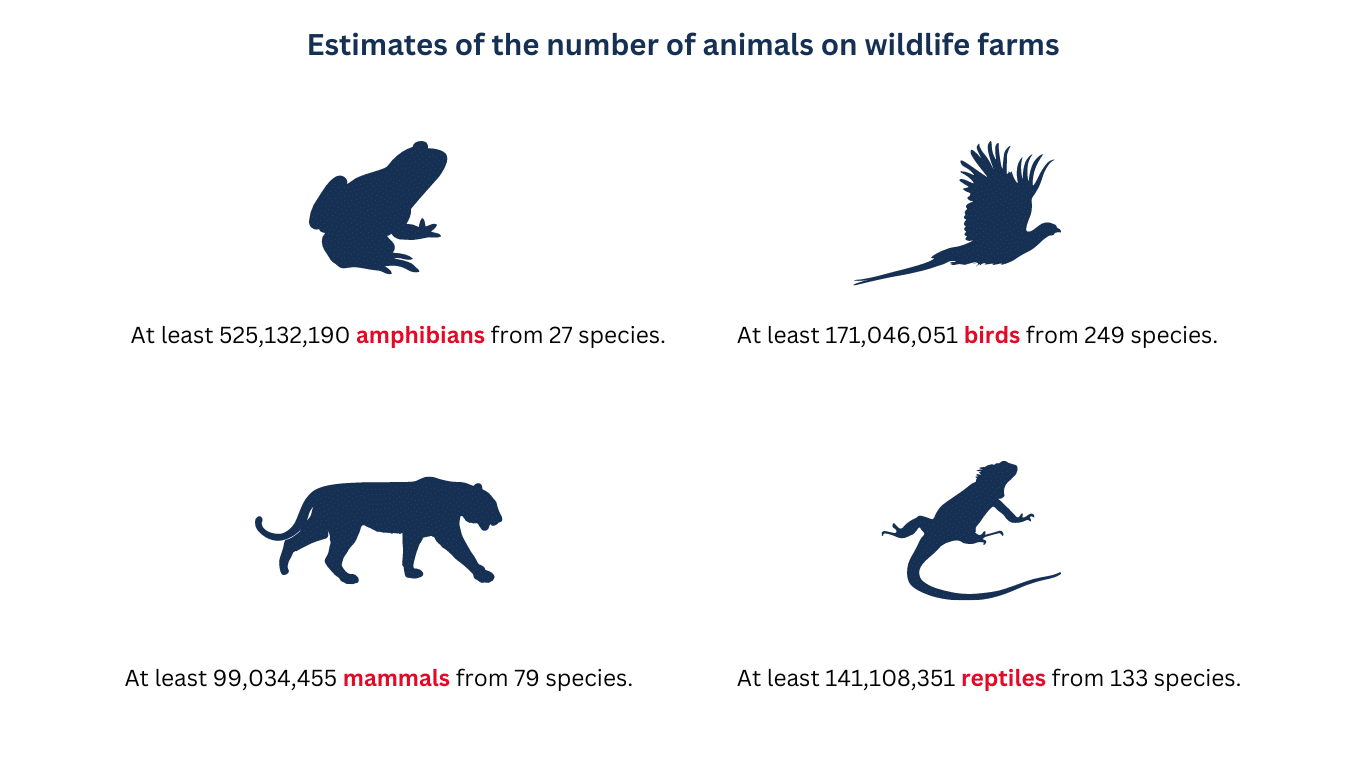

Breeding wild animals for profit is cruel and poses a threat to humans, according to a report by World Animal Protection. But what’s startling is the NGO’s estimate of the numbers — about 5.5 billion animals from around 487 wild species worldwide.

Wildlife farming is fuelled by commercial industries like the pet trade, fashion, tourism and traditional medicine. The report, “Bred for Profit”, says some breeding operations replenish their stocks from the wild, others from poaching.

The report points out that wild animals do not adapt to being farmed like domesticated animals. These have been captive for thousands of years and have undergone permanent changes to their behaviour around humans.

Wildlife farming took off in the late 20th century as the demand for wildlife and wildlife-derived products grew. Since then, the industry has boomed.

Consumers and traders seek wild animals or their parts as pets, entertainment attractions, decorations, ornaments, fashion items such as fur, leather, feathers, as an ingredient in perfumes (including deer or civet musk), luxury food, musical instruments and traditional medicine.

This rising demand, says the report, may be due to the growing human population and increasing economic prosperity as well as the commercialisation, in the media, of wild animals.

The growth of online marketplaces may also be providing consumers with increased awareness and access to the wildlife trade.

The pet trade is huge and includes demand for birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals. Favoured are parrots, lizards, snakes, tortoises, frogs and sugar gliders.

Tourist activities involving captive wild animals include swimming with dolphins, elephant rides, watching dolphins, sea lions, big cats or elephants perform, and direct interaction with wildlife such as posing for selfies, petting or feeding.

Breeding for profit

Wild animals bred for use in tourism are also exploited by other industries.

Many lions bred for cub petting and “walking with lions” in South Africa are later used for “canned” trophy hunting or killed so their bones can be sold for use in traditional medicine or tiger-bone wine.

Traditional Asian medicine can include body parts from bears (gallbladder and bile), deer (antlers or musk), pangolins (scales), tigers (bones and paws), rhinos (horns), turtles and snakes, geckoes, sea horses and many other animals.

The researchers found that over 20,000 bears, 5,000 tigers, 8,000 lions, hundreds of thousands of seahorses and millions of turtles are bred on farms for traditional medicine.

Many parts of farmed wild animals are used as fashion items. These include feathers and down (usually from ostriches, ducks and geese), fur (mainly mink, raccoons, chinchillas, sables and foxes) and leather from the skins of reptiles (mainly crocodiles and snakes).

The report says that when commercial industries become economically unviable, animals are culled in vast numbers. In 2020, Europe was the second largest producer of fur, farming 37.8 million mink, foxes, raccoons and chinchillas.

The level of culling in response to the danger of Covid is not known but was considerable.

The largest producer of these animals is China, with over 50 million farmed mink, foxes and raccoons.

A census of Vietnamese wildlife farms in 2015 found that 1,907 farms housing 158,093 animals from 45 species were no longer operating because market prices had dropped. The fate of these animals is unknown.

While conditions in cattle feedlots, piggeries and chicken hatcheries often find their way into the public eye, wildlife farms tend to fly below the radar.

Big numbers

- Millions of crocodiles in 47 countries are farmed for their skins and meat.

- More than 300 million turtles are farmed in China alone.

- Nearly 100 million foxes, mink and raccoons are farmed in 27 countries.

- Almost 9,500 deer farms hold more than 452,000 sika deer.

- Bear farms hold 24,000 Asiatic bears on farms across China, Vietnam, Lao PDR, Myanmar and South Korea.

- Tigers were found to be farmed in their thousands in several countries, including South Africa.

- Between 8,000 and 12,000 lions are kept on 366 farms in South Africa.

- Millions of ostriches are recorded on farms in over 20 countries.

There was little information on the size of wildlife farms, although one report from Vietnam documented 4,099 farms containing more than 996,000 animals from 175 species.

Of these farms, at least 24 held more than 5,000 animals. The largest farm contained almost 54,000 crocodiles.

A third of species recorded on farms are considered near threatened, vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Disease warning

Zoonotic diseases are infectious and can spread between animals and people, especially when wild animals are in close proximity to humans.

The report warns that wildlife farms create opportunities for disease transmission because of the high concentrations of animals, poor hygiene and regular human contact for husbandry purposes.

It says zoonotic disease outbreaks are thought to cause over two million human deaths a year, and substantial human illness.

They also hit financially: the Covid pandemic — undoubtedly of wildlife origin — is estimated to have cost the global economy as much as $16-trillion.

Of the zoonotic diseases in human populations between 1940 and 2004, 72% were of wildlife origin.

There are no global regulations governing pathogen screening for traded wildlife, but in lions alone, 63 pathogens have been recorded.

Value to conservation

Some conservationists, the report says, argue that wildlife farms could benefit conservation by providing competition on the market and reducing the incentive to take wild animals for money. There is, however, very little published evidence to support this.

“Wildlife farming could negatively affect wild populations because wild-caught animals are sometimes used to supplement captive ‘stock’ when farmed products cannot meet consumer demand, and because farms can struggle to breed wildlife in captivity.

“Wildlife farms can also open the door to criminal activity, such as the laundering of wild-caught animals through registered farms.”

Farming does not necessarily help the recovery of wild populations: tigers have been farmed in China for decades, yet in the wild, they are endangered and their numbers are decreasing.

Bears have been farmed in Vietnam since the 1990s, yet bear populations in Vietnam are small and falling.

South Africa is one of the few countries where wildlife farming has saved a species, bringing rhinos back from near local extinction, and substantially increasing elephant and antelope populations. Its record with lions, however, has been negative.

Generally, though, where farmed wildlife is returned to the wild, there is a risk of genetic mixing of wild populations and the introduction of diseases, potentially leading to the extinction of some genetically distinct species.

Suffering for profit

According to the report, no captive environment can fully replicate a wild animal’s natural habitat and the likelihood of suffering is far greater in commercial facilities where profit is the goal.

Welfare concerns documented on wildlife farms include disease, malnourishment, stress-induced behaviours, injuries, infected wounds, cannibalism, physical abnormalities caused by inbreeding and premature death.

Breeding wildlife in small, captive populations, says the report, can also cause inbreeding and subsequent deformities.

The lion problem

The report goes into the issue of South Africa’s lion farming in detail, noting that the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment has initiated a process to shut it down.

This has followed a global outcry over “canned” hunting and media revelations of horrific conditions on some lion farms, including inbreeding, mange, starvation and the removal of small cubs for tourists who pay to pet them.

Of concern has also been the sale of lion skeletons for traditional medicine and tiger-bone wine because breeding for bones does not require lions to be in good condition while alive.

The report recommends a clear exit pathway for lion farms, clear communication with farmers about a timeline, the banning of further breeding or permits to own lions, a ban on hunting trophy exports and the establishment of a fund to retrain workers dependent on lion farm work.

The report concludes that the farming of wild animals for commercial gain is a cruel, non-essential industry and should be banned globally.

It also poses a considerable risk of zoonotic pathogens reaching humans — potentially to pandemic levels. At the same time, local communities, whose livelihoods can depend entirely on wildlife farms, see little of the vast profits from the wildlife trade.

“We must ensure this is the last generation of wildlife to suffer in captivity and be farmed and exploited for commercial gain. It’s time to end wildlife farming for good.”