Midterm season, and Meliora Weekend basically flattened the staff of the CT on Oct. 7, rendering our production schedule — from noon to 6 p.m. on Sundays in Wilson Commons 103, for those interested — semi-useless.

Thus, instead of hanging out in the office all day, some of our staff decided to touch grass that afternoon and enjoy the performing arts.

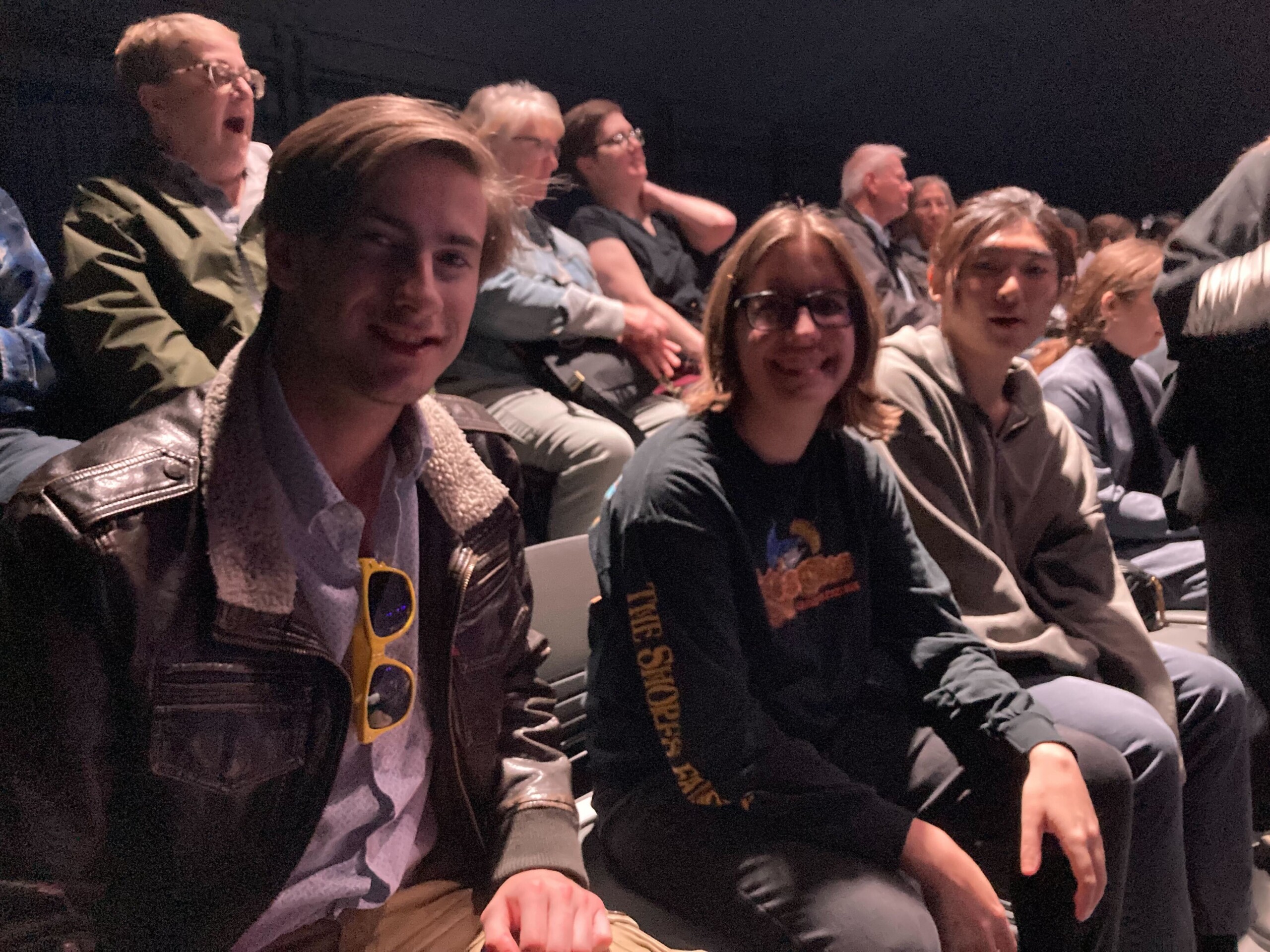

Our backgrounds with the University’s International Theater Program (colloquially referred to as ‘Todd shows’) are varied — one of us has been a frequent reviewer of campus productions, a couple of us have seen one or two shows, and for two of us (the first-years) this was the first of Todd’s performances to grace their retinas.

Even so, we all found ourselves in the Sloan Performing Arts Center (SPAC), underneath the trellises of white clothing, unaware of the tomfoolery that was about to unfold. And boy, was there tomfoolery. And shenanigans. And a surprising amount of choreography.

CT staff covered the beat (and simultaneously, did some team bonding) at “Orlando.”

“Orlando,” written by Virginia Woolf, adapted by Sarah Ruhl, and produced by the International Theatre Program, is — according to director Will Pomerantz — a “sharply observed comedy of manners, spotlighting the absurdities that female-identifying individuals endured for centuries (and continue to endure in our own time).”

The novel has been highlighted as a big part of queer literature, with Orlando’s shifting perception of personal gender being a focal point of the piece. Ruhl’s stage adaptation, which she says “[presses] hard on the musculature of the original, and without leaving a bruise,” stays faithful to Woolf’s writing.

Both CT editors and general members were in attendance.

Pomerantz takes the faithfulness of the dialogue and throws it into a modernized fever dream of staging, with cuts of songs including Billie Eilish’s recent “Barbie” hit “What Was I Made For,” They Might Be Giants’ “Istanbul (Not Constantinople),” and The Monkees’ “I’m a Believer” (hilariously referred to by one of our writers in the CT office as “that Shrek song”).

In addition, “Orlando” boasts multiple dance breaks, plenty of gorgeous costume changes, and enough balloons, packing peanuts, and random one-off props to make any theater tech nerd more anxiously giddy than normal.

As a result of all this — and more — “Orlando” may be the second most campy thing to hit campus — falling just short of Sigma Delta Tau’s annual Mr. UofR pageant.

Todd Theatre is often known for its dramas — its “Crucibles,” its “King Richards,” and its shows titled after stupid, expletive-ridden birds. As a result, the new comedic territory that “Orlando” skates into feels fresh and unexplored, especially for all the familiar faces.

At least half the cast have been staples of Todd Theatre for at least the past few semesters, and seeing them get to flex their humor muscles after multiple productions of desperate shouting was a nice relief from the norm.

Sophomore Stella Carleton (who played Elizabeth Proctor in last year’s “The Crucible”) leads “Orlando’s” merry band as the show’s titular protagonist, and compellingly chameleons in and out of the childlike wonder of a precocious boy and the growing sadness of a lost soul while wearing what amounts to a gussied-up morph suit.

That’s not to say that any of the chorus fell flat in comparison. “Orlando’s” script hinges on group storytelling — and everyone commits to the bits hard.

Some examples (of the many we could choose from):

- Props to junior Gabe Pierce for swaggering around in a pair of heels tall enough to scare an America’s Next Top Model contestant (and for — when we went — playing off a very real fall for very relieved laughs).

- Sophomore Ember Johnson pulls off being legitimately scary amidst a hilariously poofy ball gown, and may have done some of the most accurate accent work any of us have ever seen in a Todd show (which tracks, given their stint in TOOP’s Pride and Prejudice last fall).

- Senior Britt Broadus pulls off both a sustained Russian accent and a stiff upper lip — props to voice coaching from senior lecturer Sara Bickweat Penner — while also, like senior Chris Riveros, playing off Carleton sweetly for the softer, more intimate beats of the show.

On a technical level, SPAC’s black box, Smith Theater, was covered in barren plywood — potentially an homage to the stripping down of Orlando and their identity over the course of the show.

Three large wooden tables on industrial castors served as the main set pieces for most scenes, standing in for everything from a Russian ambassador’s ship to a London theater.

To continue with the wood motif, gender, for Orlando, is like an oak tree — something that looks sturdy. But trees sway, and even fall — and by the second act, Orlando discovers her connection with womanhood after having lived as a man for decades.

The poem that Orlando works on throughout the show, “The Oak Tree,” is something they are unable to put the words to for centuries — until the revelation of her womanhood sinks in. This recurring theme is almost always played for laughs — something Pomerantz seems to have narrowed in on.

“Orlando” offsets thought provoking questions about gender, sexuality, depression, and life with hilarious wigs and stunts. In some ways, that offsetting is delightfully entertaining; in others, it feels as if it sometimes passes over the chance to address more interesting questions about gender identity in Orlando’s world.

In a similar way, while the cast does a great job handling all the hats they have to wear, the lack of gender fluidity in the casting of ensemble roles does not facilitate the questioning of how we perceive gender in society (which the show reinforces as having basis in dress and performance).

Why not have one of Orlando’s courtly loves be played by a cis man in the cast, tutu and all? Why not have the performance of “Othello” cast two men as Othello and Desdemona (as was common for Elizabethan era Shakespeare)?

Beyond the questions of gender, sexuality, and comedic timing, “Orlando” is no stranger to the darker times of life. Centuries pass, and characters are lost — only to reappear, hundreds of years later, as nothing more than memory.

Gender in “Orlando” is vital — but so is the certainty of death.

“Orlando” actively engages with the concept of gender and sexuality. While the humor may shy away from the most revelatory kind of wit, the text’s snappy timing does strike at some hidden depth.

Beyond the love and the laughter, Orlando’s plight is a struggle with loss. We’re born, we fight, we die — the pattern is age-old, and the outcome is certain. Unless, of course, you’re Orlando: living and loving, perhaps forever, waiting for an end that does not come.

For “Orlando” the production, however, an end does come.

Despite centuries ruled by loneliness and melancholy, Orlando never ceases to engage with her vibrant and colorful life. She’s haunted, yes, but she makes sure to live — and comes to understand, though all things die, we have to live in the moment.

We’re bracketed by the past and the future — sometimes, almost crushingly so. But the present keeps us anchored, and the present — emotional and real — is often what defines us. For better or worse — the days roll on. The next day will come.

This “Orlando” ends on a light note: Orlando, steeped in the memory of her past loves, finally comes to terms with the seemingly inevitable.

“The white arch of a thousand deaths” stands, impossible and inevitable, before her — and as all the white shirts, the white trousers, and the white dresses are slowly brought down from their racks around the stage, Orlando un-closets herself to face whatever comes next.