Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

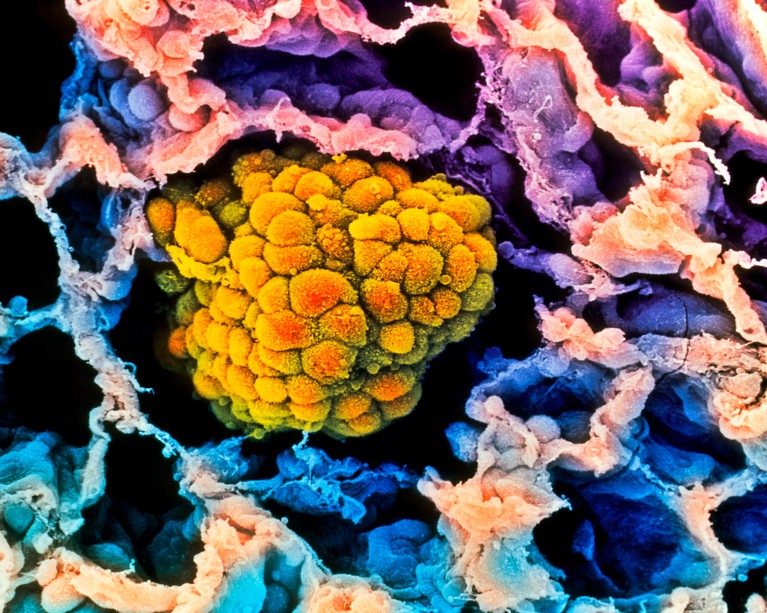

A tumour (artificially coloured) fills the alveolus of a human lung. Some evidence suggests that risk of these cancers decreases with age. Credit: Moredun Animal Health Ltd/Science Photo Library

Why lung cancer risk declines in old age

Lung cells in old mice behave as if they were iron deficient, which limits their ability for rapid, cancerous growth. This could explain why lung tumours in older mice are smaller and less frequent than in younger mice. The protein that affects the iron metabolism in mice also exists in humans, which could hint at why people over 75 are less likely to get lung cancer. But it’s important to note that the mice’s cancer was triggered suddenly with a genetic switch: in humans, cancer-causing mutations usually accumulate over decades, says molecular oncologist Ana Gomes.

Nature | 5 min read

Reference: bioRxiv preprint 1 & preprint 2 (not peer reviewed)

Western scientists publish rejects faster

Authors in Western countries are almost 6% more likely than those based in other parts of the world to successfully publish a paper after it has been rejected, according to an analysis of 126,000 rejected manuscripts. These authors also found a home for their rejected manuscripts 23 days faster on average. “Maybe it’s something about being in the right networks and being able to get the right kind of advice at the right time,” says sociologist Misha Teplitskiy. Other factors playing into the discrepancy could be cultural. For instance, many journals are written in English, which puts some researchers at a disadvantage.

Nature | 4 min read

Reference: SSRN preprint (not peer-reviewed)

Ants perform life-saving amputations

Florida carpenter ants (Camponotus floridanus) bite off injured nest mates’ limbs to save them from deadly infections. It’s the first example of animals other than humans performing such life-saving amputations. “The ant presents its injured leg and calmly sits there while another ant gnaws it off,” explains animal ecologist and study co-author Erik Frank. “As soon as the leg drops off, the ant presents the newly amputated wound and the other ant finishes the job by cleaning it.”

The New York Times | 5 min read

Reference: Current Biology paper

Features & opinion

Climate change worsens the housing crisis

Thousands of people are being displaced across the Arctic as wildfires, floods and other symptoms of climate change threaten housing and infrastructure. To tackle both the housing and the climate crisis, governments must listen to Indigenous and local communities, argues geographer Julia Christensen. “Northern communities should be equipped to respond to their own needs through self-building, self-repair and community-led housing planning.”

Nature | 5 min read

Science priorities for the next UK government

Tomorrow voters in the United Kingdom go to the polls. The incoming government must reconnect with the scientific community, argues a Nature editorial. It recommends that ministers take a global view of science, address a growing crisis in university finances and guarantee research autonomy.

Nature | 5 min read

RNA pesticides promise precision killing

RNA-based pesticides promise to defend crops with less damage to the environment and human health than traditional poisons. By targeting the genes in specific pests, they can leave pollinators and other species unscathed. The technology first hit the market in the US last year with SmartStax Pro, a corn variety that produces double-stranded RNA that disrupts a gene in corn rootworm (Diabrotica spp.). And a pesticide sold as Calantha, approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency in January, uses RNA interference to discombobulate a gene unique to the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and its close relatives. Critics say more work needs to be done to ensure that RNA-pesticides don’t harm non-target species.

Science | 12 min read

Where I work

N. M. Ganesh Babu heads the Centre for Herbal Gardens at the University of Trans-Disciplinary Health Sciences and Technology in Bengaluru, India.Credit: Sayan Hazra for Nature

Field botanist N. M. Ganesh Babu conducts botanical surveys in forests all over India with the help of local communities. His team includes doctors in traditional medicine who know the cultural significance of the plants that they work with. “My grandparents and my mother had a tremendous knowledge of plants,” he says. “So much inherited wisdom of this kind has already vanished.” Babu and his colleagues have developed techniques to propagate almost 800 wild species from seed, and have created an ethnomedicinal garden spanning 20 acres that showcases the vast array of plant species used in various traditional health practices — as well as a native-plant landscaping business at the university.

(Nature | 3 min read) (Sayan Hazra for Nature)