Climate change and climate action are socially and politically divisive topics in many countries. In addition to contributing to political disparity, climate research is also affected by political context, with consequences not only for scientists but for society as well.

The Mauna Loa Observatory has maintained the longest record of atmospheric CO2, with measurements started more than six decades ago. The resultant Keeling Curve showcases the steady increase in CO2 concentrations over time, and has become a staple in climate change research and discourse. However, the collection of these and other climate data is now under threat, with some records already interrupted.

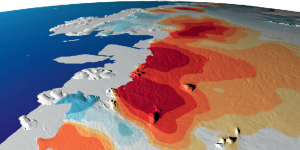

Credit: NASA’S SCIENTIFIC VISUALIZATION STUDIO / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Tackling climate change on all levels requires broad scale collaboration1. In addition to action on adaptation and mitigation, which is driven largely on a political level, procuring the data needed to inform that action also relies on international efforts2. Science has long been an international effort, and collaboration between scientists has often transcended political boundaries, even in the face of violent conflict3. However, work under inhospitable political conditions faces enormous challenges, and recent political developments have further impeded scientific work and collaboration globally.

Long-term data such as the Mauna Loa record are critical to climate science. Long-term records are often needed to detect trends over the noise created by shorter term variability and climate fluctuations such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation cycle. Long-term data are also essential for validating and informing models of the physical climate system, as well as climate change impacts. Owing to the global nature of the climate system, cooperation across borders is essential for both the collection of and access to such data. Unfortunately, similar to nationalist movements in the past decade4, recent political developments have endangered data collection and access.

The war resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the subsequent political tension, derailed collaboration between Russian and other climate researchers. This has been particularly deeply felt in the field of Arctic science, where the loss of data from Russian research stations has created a hole in coverage that limits understanding of current and future Arctic change5, including detection of carbon feedbacks6.

More recently, changes in national and international US policy are causing waves of disruption and long-term damage to both scientific and political climate efforts. In addition to changes on the global political stage, such as the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement and cuts to aid programmes that provided critical climate finance, government actions have also already deeply impacted research and access to data.

Soon after the Trump administration took office, climate data and analytical tools were removed from many government websites, including information related to environmental justice and climate data needed by farmers. Following this were severe cuts to government funding and agencies, including staffing at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which have stopped larger projects around climate modelling and forecasting, with consequences felt on the other side of the world. These cuts have also impacted data collection and monitoring that inform climate-sensitive sectors ranging from disaster preparedness to fisheries. Future cuts are also planned, including those threatening the Mauna Loa observatory and CO2 record.

The clear and immediate consequences that the actions ostensibly taken by just two countries (Russia and the United States) have for climate researchers and stakeholders worldwide demonstrate how fundamental international efforts are to addressing the climate crisis. In response, scientists and legal groups have called for action, initiating legal processes to ensure data access, for example, or calls for open repositories to safeguard data7 critical for climate research, action and adaptation.

The realities of climate change have clearly illustrated how connected the world is, both through the shared global nature of climate as well as through phenomena such as teleconnections, which link processes and impacts across large distances. All levels of society, including scientists and politicians, must harness the connection inherent in nature to adapt to and mitigate climate change, and ensure that the necessary data are there to support decision-making.

References

-

Nat. Clim. Change 15, 227 (2025).

-

Durack, P., Lee, T., Vinogradova, N. & Stammer, D. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 228–231 (2016).

-

Glausiusz, J. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00692-1 (2025).

Google Scholar

-

Jeffries, E. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 469–471 (2017).

-

López-Blanco, E. et al. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 152–155 (2024).

-

Schuur, E. A. G., Pallandt, M. & Göckede, M. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 410–411 (2024).

-

Büntgen, U., Trnka, M., Hulme, M. & Esper, J. npj Clim. Action 4, 9 (2025).

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Data under duress.

Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02323-z

-

Published: 07 April 2025

-

Issue Date: April 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02323-z