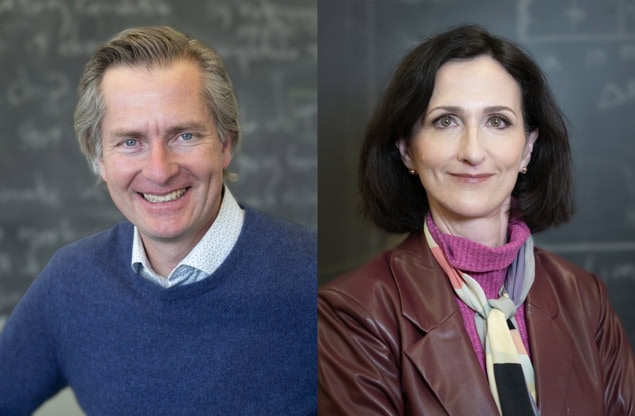

Exoplanet researchers David Charbonneau from Harvard University and Sara Seager from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have won the 2024 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics. The laureates, who will share the $1m prize, have been recognized by the Kavli Foundation and the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters for their work characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets. The foundation was set up by the Norwegian-American physicist and philanthropist Fred Kavli in 2000.

Since the first planet around other stars was spotted in the 1990s, new techniques and telescopes have helped discover more than 5000 exoplanets to date. Spectroscopic measurements of the chemical compositions in the atmospheres of some exoplanets have also been made, revealing whether they are suitable for life. Such methods can detect atomic and molecular species in planetary atmospheres around both giant and rocky planets.

The characterization of exoplanet atmospheres is still a developing field but it is one that both Charbonneau and Seager have pioneered. In 1999, Charbonneau led the team that used the transit method – a technique that measures the tiny amount of light blocked by such a planet as it passes in front of its host star – to discover a giant exoplanet HD 209458b.

In the early 2000s, he then pioneered the use of space-based observatories, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, to perform the first studies of the atmosphere of giant extrasolar planets. This involved taking molecular spectra using both filtered starlight and infrared emission from the planets themselves.

Seager, meanwhile, pioneered the theoretical study of planetary atmospheres and predicted the presence of atomic and molecular species that should be detectable by transit spectroscopy, notably the alkali gases. She improved our knowledge of planets with masses below Neptune while finding that higher-mass variants are dominated by hydrogen and helium. Seager also provided new concepts for our understanding of the habitable zone, where liquid water can exist, and thus established the importance of a variety of biomarkers such as oxygen, ozone and carbon dioxide.

Exciting opportunities ahead

Seager told Physics World she is “absolutely thrilled” to receive the prize with Charbonneau. “It’s a significant milestone that exoplanets are recognized with this award for the first time,” she says. “With the James Webb Space Telescope operational and continuous discoveries about exoplanet atmospheres, our field is thriving. I am most looking forward to the future when we can identify a true Earth twin, an Earth-like planet orbiting a Sun-like star.”

Seeing the Earth through alien eyes: an extraterrestrial view of our planet

Charbonneau, meanwhile, told Physics World that receiving the news was “wonderful” not just for him but the “entire community of exoplanet explorers”. “Research in exoplanets has been such an adventure,” he says. “We are constantly finding new worlds and developing new tools to learn about these worlds.”

He adds that the next “exciting opportunity” in the field is to study terrestrial worlds. “Recently some very nearby examples have been discovered orbiting small stars, which makes them accessible to our current telescopes,” he notes. “So the question is, are these indeed Earth-like, with atmospheres and oceans and even a moon, or not? And we can hope to learn the answers in only a few years.”