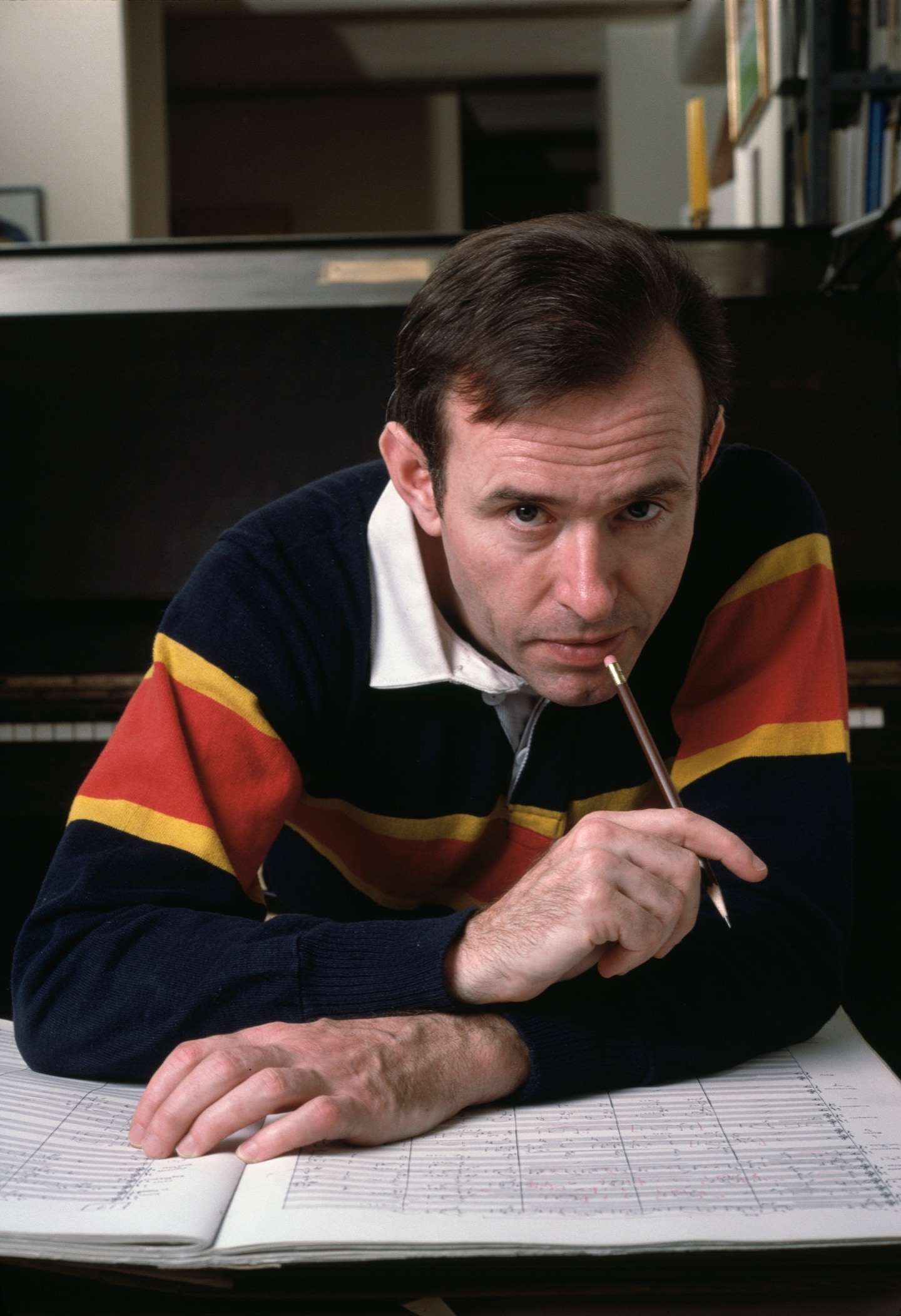

David Del Tredici, a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer who rejected the cerebral atonality of the mid-century avant-garde to write in a lush, melodious style, setting Lewis Carroll’s “Alice” books to music and later celebrating gay life in song, died Nov. 18 at his home in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan. He was 86.

The cause was complications from Parkinson’s disease, according to a statement from his publisher, Boosey & Hawkes.

A mischievous pianist-composer who reinvented himself multiple times, Mr. Del Tredici had an instinctual approach to music, writing compositions that often had more in common with the exuberant operas of Richard Strauss than the serialist work of his American contemporaries.

“I feel like I’m in a trance when I go to the keyboard, like a pure fool,” he once said. “I free-associate, and inevitably it leads to something.”

Mr. Del Tredici started out as a concert pianist, playing Liszt concertos with conductor Arthur Fiedler and the San Francisco Symphony when he was only 18. A few years later, he began to focus on composing, writing dissonant experimental pieces at a time when atonalism was king. His early work set the poems of James Joyce to cryptic, angular music through pieces such as “Syzygy” (1966), which included a section that ran backward after its midpoint, like a musical palindrome.

But beginning in 1968, Mr. Del Tredici helped launch a movement that became known as neoromanticism, writing in a warm, hummable style while incorporating the words of Carroll’s “Alice” books.

Over a span of more than 25 years, he drew on passages from texts such as “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” while writing chamber music, symphonies and a 90-minute opera — “Dum Dee Tweedle” — that brought listeners “through the looking-glass,” evoking the stories’ madcap humor and phantasmagoric imagery.

Many of his pieces incorporated instruments not usually heard in the orchestra, including banjo, electric guitar, saxophones and an enormous tam-tam. Some defied classification: “Final Alice,” an hour-long work for soprano and orchestra, bridged the realms of opera and orchestral music while dramatizing the last two chapters of “Wonderland,” including Alice’s trial (the Queen of Hearts calls for her head) and her subsequent return to “dull reality.”

Reviewing the piece in the New York Times, music critic Tim Page called “Final Alice” “a hyperactive, exhilarating late-Romantic dream, which sounds like ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ on amphetamines: full of soprano whoops, lush orchestral explosions and an agreeably cracked vision of the world.”

The work premiered in 1976, performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under conductor Georg Solti, and over the next few years was performed by most of the nation’s leading orchestras. A recording of “Final Alice” became the country’s best-selling classical record, and in 1980 Mr. Del Tredici won the Pulitzer Prize for music for another “Alice” piece, “In Memory of a Summer Day,” commissioned by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and dedicated to the group’s music director, Leonard Slatkin.

In an email, Slatkin noted that Mr. Del Tredici’s work could be paradoxically “retrogressive and forward-looking at the same time.”

“Most new music played by orchestras at that time was rather severe and difficult to comprehend on first hearing,” Slatkin wrote. “Along came David, and all of a sudden we had not only melodies that people where humming for days but also lush Straussian harmonies, minimalist repetition, as well as new and extraordinary instrumental combinations.”

Some composers were dismayed by Mr. Del Tredici’s new music, deeming it overwrought and indulgent. Conductor Erich Leinsdorf dismissed “Final Alice” as “totally without merit,” and when the piece was performed by the New York Philharmonic, it was “booed as well as cheered,” according to Bomb magazine.

Mr. Del Tredici seemed not to care. As he told it, he was simply following his instincts, and he had turned to tonal music because it was better suited for Carroll’s words. “As a ‘modern’ composer, I kept waiting to write the obligatory dissonances, for the wrong notes to arrive. But they never did,” he told Page.

He added that Carroll’s writings had appealed to him in part because of their “combination of wit and whimsy and mathematical exactitude.”

But there was another reason as well: Mr. Del Tredici believed that Carroll was “a closeted man,” with a secret love of young girls — a claim that biographers have debated for years. As a gay man who had been bullied and ostracized as a child, Mr. Del Tredici said, he felt a kinship of sorts with Carroll, even as he openly discussed his sexuality instead of hiding it.

“There is so much conservatism in classical music. It is the last refuge of conservatism,” he told American Public Media in a 2002 interview. “When you think of plays, poetry, pop songs, there is all kinds of sexuality thrown in there, and it’s okay. In classical music — forget it! So I like to set really provocative texts and I think, ‘Why not?’ ”

Mr. Del Tredici went on to explore gay life and sexuality through his music, once again drawing on poetry for inspiration. His piece “Gay Life” (2001), a 45-minute song cycle commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony, incorporated verses by Allen Ginsberg and Thom Gunn. One section, a setting of Paul Monette’s poem “Here,” was written in memory of Mr. Del Tredici’s 34-year-old partner, Paul Arcomano, who died of complications from AIDS in 1993.

His later works included “Bullycide” (2013), a half-hour piece for piano and string quintet, inspired by the suicides of five young gay men who had been bullied because of their sexuality. The piece suggested loss and suffering but ended with a bright quotation of Schubert’s “Trout Quintet.”

It was a typically optimistic gesture by Mr. Del Tredici.

“I remember standing on a corner, sometime before I turned 5,” he told the Times in 1983, recalling a pivotal moment that he sought to channel in his music. “I looked up at the flowers and the sky, and suddenly had this overwhelming sensation of happiness that I would never truly grow up.

“I want to trap the ecstasy of life within my music,” he continued. “I want to create sounds so beautiful that time will stop.”

A fateful piano lesson

The oldest of five children, David Walter Del Tredici was born in Cloverdale, Calif., on March 16, 1937. He grew up in San Anselmo, about 20 miles north of San Francisco. His father was an accountant, his mother a homemaker.

No one in the family was especially musical, but he began taking piano lessons at 12, after a nun at Mr. Del Tredici’s Catholic school taught him to play “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

Mr. Del Tredici studied under pianist Bernhard Abramowitsch and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, planning to become a concert pianist. He lost interest in the instrument in 1958, when he went to the Aspen Music Festival and School in Colorado and clashed with one of his teachers.

“Deciding that a change was necessary, I sat down and wrote my first composition,” he recalled. The piece, a jagged piano work called “Soliloquy,” impressed composer-in-residence Darius Milhaud, whose encouragement gave Mr. Del Tredici the confidence he needed to seriously study composition.

After graduating in 1959, Mr. Del Tredici continued his composition studies at Princeton University, receiving a master’s degree in 1964.

He later taught at schools including Harvard University, where his students included composer John Adams, as well as Boston University, Yale University and the City College of New York, joining the faculty a few years after he won the Pulitzer.

The prize brought him new fame and renown, including through a composer-in-residence position at the New York Philharmonic. It also fueled a descent into alcoholism.

“For about 10 years I was a runaway drunk,” he told Bomb. After he got sober, he said, he realized he was also a sex addict. “Eventually, I discovered my spirituality and intimacy with people as people — not as sex objects. So I began at age 55 to have real friends.”

Survivors include a sister and two brothers.

Mr. Del Tredici was still composing large-scale works late in his career: “Paul Revere’s Ride,” a choral and orchestral piece, was nominated for a Grammy in 2006, and “Herrick’s Oratorio,” which set verses by 17th-century poet Robert Herrick to music, premiered in New York in May.

Interviewed by the Times earlier this year, Mr. Del Tredici said that he was considering writing an opera inspired by his experience with Parkinson’s disease, and likened it to his earlier effort to write about gay themes. “I like being open,” he said, “about all the things that are hard to be open about.”