Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Hindsight is always in high definition for investors. That sense of clarity will be uncomfortable for anyone who has unwittingly invested in the bond market in recent years. Yields have soared — they are at 15-year highs for gilts — and capital values have tumbled.

This is particularly jarring for savers with defined contribution pension schemes. Savings companies may, in some cases, have transferred their nest eggs into bonds at the worst possible time.

That could apply when money went into so-called lifestyle funds through default or choice. These embody a one-size-fits-all approach to asset allocation. Lifestyle funds give younger savers heavy exposure to equities with the aspiration of long-term growth. Older customers are funnelled into bonds with the aim of locking in gains.

“I see many clients that have four or five pensions from their working lives and typically two of these have been lifestyled,” said David Hearne, a chartered financial planner.

Mature savers who were shunted into bonds at record-high prices may now find their lifestyle fund will no longer finance the retirement lifestyles they planned for.

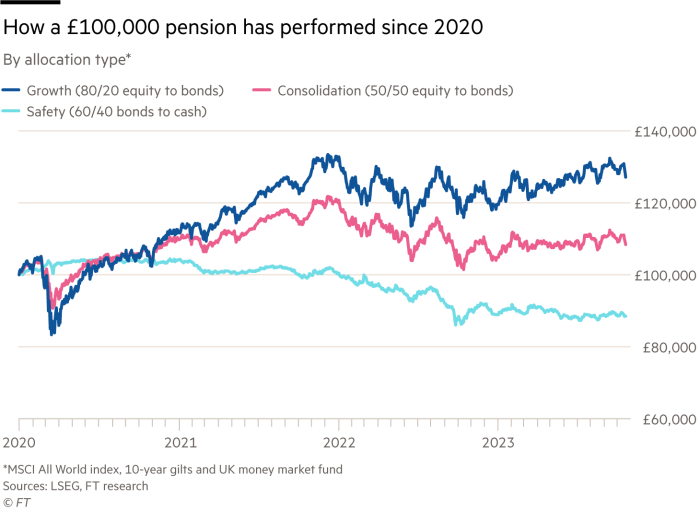

The difference could be huge. A simplified lifestyle fund for a younger saver devised by Lex and split 80/20 between equities and bonds would be up 30 per cent since the start of 2020. A corresponding fund for an older counterpart divided 60/40 between bonds and cash would have made a 12 per cent loss.

Default allocations to lifestyle funds are a “necessary evil” for pension managers responsible for thousands of people, said Laith Khalaf at AJ Bell. But he adds: “The one-size-fits-all approach is incompatible with the broader range of retirement choices available today.”

UK pension reforms in 2015 gave retirees greater flexibility. Before then, they mostly had to buy annuities. Bond-heavy annuity funds hedged that liability as retirement approached. Since 2015, most DC pensioners have used flexible plans to draw down cash or income.

This extends the investment period, which argues for greater exposure to equities for people in the early, active years of retirement. The little-acknowledged danger for savers is therefore that savings companies may shunt their money into low-return lifestyle funds too early.

There will be pressure on them from compliance departments to reduce regulatory risk with a “safety first” approach. But the safety provided by bonds when interest rates are volatile has lately proved illusory.

The Lex team is interested in hearing more from readers. Please tell us what you think of lifestyle funds in the comments section below