The first time Elle Barbeito skinned an invasive Burmese python she almost lost her lunch. Twice. Initially she nicked the snake’s stomach with the razor and semi-digested prey spilled out. Things got even more disgusting farther down the digestive system.

Despite the disgust, Barbeito was after beauty. And she found it, not only in the edgy fashion pieces she makes out of invasive Burmese pythons that she and her father catch, but in the larger process of removing a magnificent but highly destructive predator from her beloved Florida.

It’s a blisteringly hot morning in her father’s backyard in Cutler Bay, south of Miami, and the 27-year-old Barbeito pinches the skin on the belly of a thawing 7-foot python and starts meticulously cutting. “The pinching is to keep the razor away from the flesh and organs,” she says, swatting away the gathering flies.

She wears dozens of bracelets. Ornate tattoos range up each arm and down the side of her fingers. Her chrome fingernails glisten against the dark brown and taupe of snake skin.

Once she frees enough skin to get a grip, she stands, grabs the skin in one hand and the snake’s head in the other and steadily pulls as if aiming a bow and arrow. The skin peels slowly and perfectly away from the body.

After three or four more yanks, the skin, beautiful, elastic yet tough, is free. The stunning coffee, tan and taupe camouflage that makes for beautiful garments also makes them nearly invisible in the field.

The invasive predators, which have grown to 19 feet in Florida, have decimated South Florida wilderness areas for decades, reducing mammal sightings by as much as 98% in parts of Everglades National Park and throwing ecosystems off kilter.

Brought here by the exotic pet trade in the 1970s and ’80s, the snakes escaped, bred copiously in the wild, and have now moved as far north as Lake Okeechobee and the Fort Myers suburbs.

Barbeito will soak today’s skin in a mason jar full of alcohol and glycerin for two weeks, then take it to her grandmother’s house where she’ll craft it into bustiers, bikini tops, watch bands and belts. Some of her designs feel a bit dangerous, perfect for the Miami or Brooklyn nightlife scene, but others evoke western wear, such as a cowboy belt that would impress on a big night out two-stepping.

The genesis

Barbeito, a native Miamian of Cuban background, was in New York City studying fashion design six years ago at the Pratt Institute when her father, Mark Yon, failed to return a late-night text. She got him on the phone the next day. “He was like, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I was in the Everglades hunting pythons,’” she says. “I was like, ‘WHAT!’”

As soon as she was back in Miami, she begged him to let her tag along into the Everglades as he worked as a contracted python hunter with the South Florida Water Management District.

She was stunned when she watched him catch a snake. “I was like, ‘What the hell? This is crazy, but also super-fascinating.’ And a really cool way to spend time with my dad.”

Barbeito catches the predators as well. At first, her father only allowed her to snag 2- to 3-foot hatchlings, but she’s since graduated to 8-footers. When she finally caught an adult snake, her father and his buddies were cheering her on. “It was like an initiation,” she says.

The killing of the snakes, which her father handles as a contractor, isn’t so fun. “That part sucks. It’s not like we enjoy killing this beautiful snake. It breaks my dad’s heart. But we recognize that the reason they’re here is because of human error, and it’s our responsibility to fix it. He’s taught me that it’s better to look at the bigger picture and to realize that it’s better to preserve the entire Everglades than just these snakes.”

Her father started skinning snakes because it felt like a waste not to. “As soon as I found out he was preserving the skins, I was like, ‘Oh, I should see if I can use this stuff (for clothing).’ He had skins in the shed, and my stepmom was like, ‘Give them to her!’”

Farm-to-table is a culinary catchword, but with Barbeito’s work, there is a field-to-fashion parallel. You can buy a $4,800 python leather bag from a European designer, but that leather comes from python farms in Asia — those designers are not catching and skinning snakes. “It’s one thing to look at photos, it’s another thing to take (the animal) apart. The first time I did it I was fascinated by the way everything (the tissue, flesh, skin, membranes) was connected to make this beautiful snake. It was spiritual, in a way.”

“A lot of times fashion designers don’t have that kind of relationship with their material, they don’t have the privilege of knowing where this came from,” says Barbeito.

When she started posting her work on social media, there was love, but also some hate.

“People didn’t realize they were invasive, so they thought I was just butchering snakes. I would have so many people on my Instagram like, ‘You’re a monster! What are you doing? You’re just killing these snakes to make accessories!’ I get it. But once I explained it, they were like, ‘Oh, all right, I’ll shut up now.’”

Grandma’s house

Barbeito does her designing and sewing at her grandmother’s house in Kendall, a few miles from the Everglades, where she and her father catch snakes.

The house is a bit of menagerie, with three little dogs barking, a big parrot whistling, a taxidermied alligator head next to the sewing machine and 8-foot pythons’ skins pinned to a board.

All of her pieces are sold online, directly to customers and she makes them to order. Top sellers include the bikini tops ($525) and bustiers ($2,500) as nightlife items, as well as the unisex belts ($575) and the bootstraps ($375), which can go on any boot.

“When people buy pieces from me, they say it’s the best conversation starter — there’s a whole story that comes along with it. It’s really cool, because it’s a way to educate people.”

Her latest collection, Florida Girls, is an homage to girls and women who make Florida unique. “There are a lot of people moving here without understanding what makes Florida what it is. Everybody is like, ‘Florida man this, Florida man that,’ and I was like, ‘Okay but what about Florida girls?’”

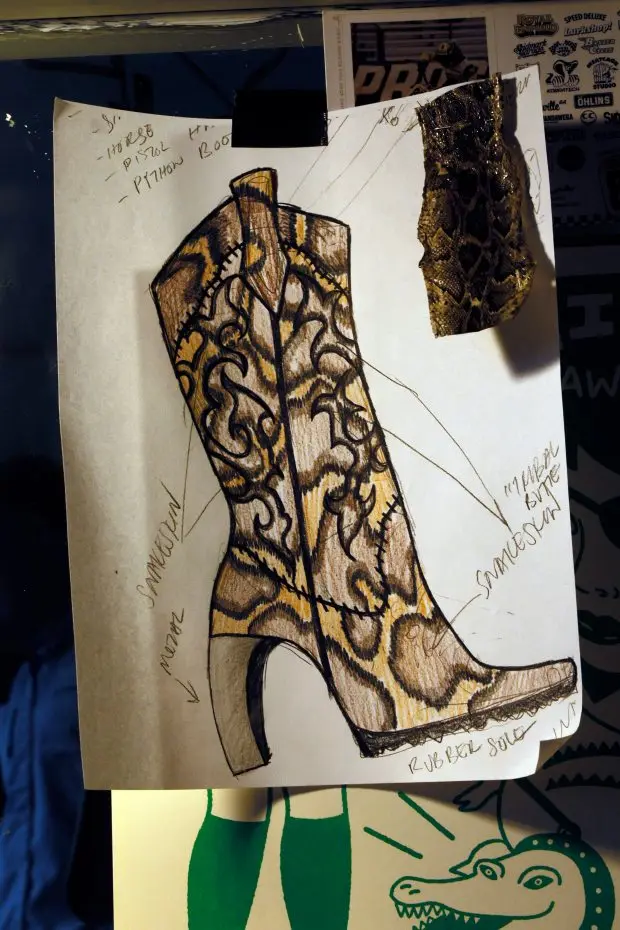

She met female cattle ranchers in their 70s (“the toughest women I had ever met,” she says), a woman who races flat track motorcycles, and two teenage cowgirls in Homestead who compete in barrel racing at rodeos. Each has inspired pieces in the collection, including a python jumpsuit, and boots that are a little bit cowgirl, a little bit rock ‘n’ roll.

Florida Girls will also be a documentary film about the women who inspired the collection. Last year she won funding from Oolite Arts to produce it, and illuminate “the complex relationships between people, place and progress as the state faces additional development and growth.”

Barbeito is not cranking out thousands of pieces and selling them retail. Her work is the opposite of fast fashion. “I am very concerned with sustainability to the point where it stops me from making things,” she says. “I was trying to find a way to make this where it’s solving a problem rather than adding to a problem.

Some might say her small-scale operation can’t be making a difference. “To me it makes a difference. It’s my whole life. And it’s not my responsibility to save the whole world. … As long as I’m doing my part, and if more people were doing their part, then it would be part of a greater solution.”

Bill Kearney covers the environment, the outdoors and tropical weather. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Instagram @billkearney or on X @billkearney6.