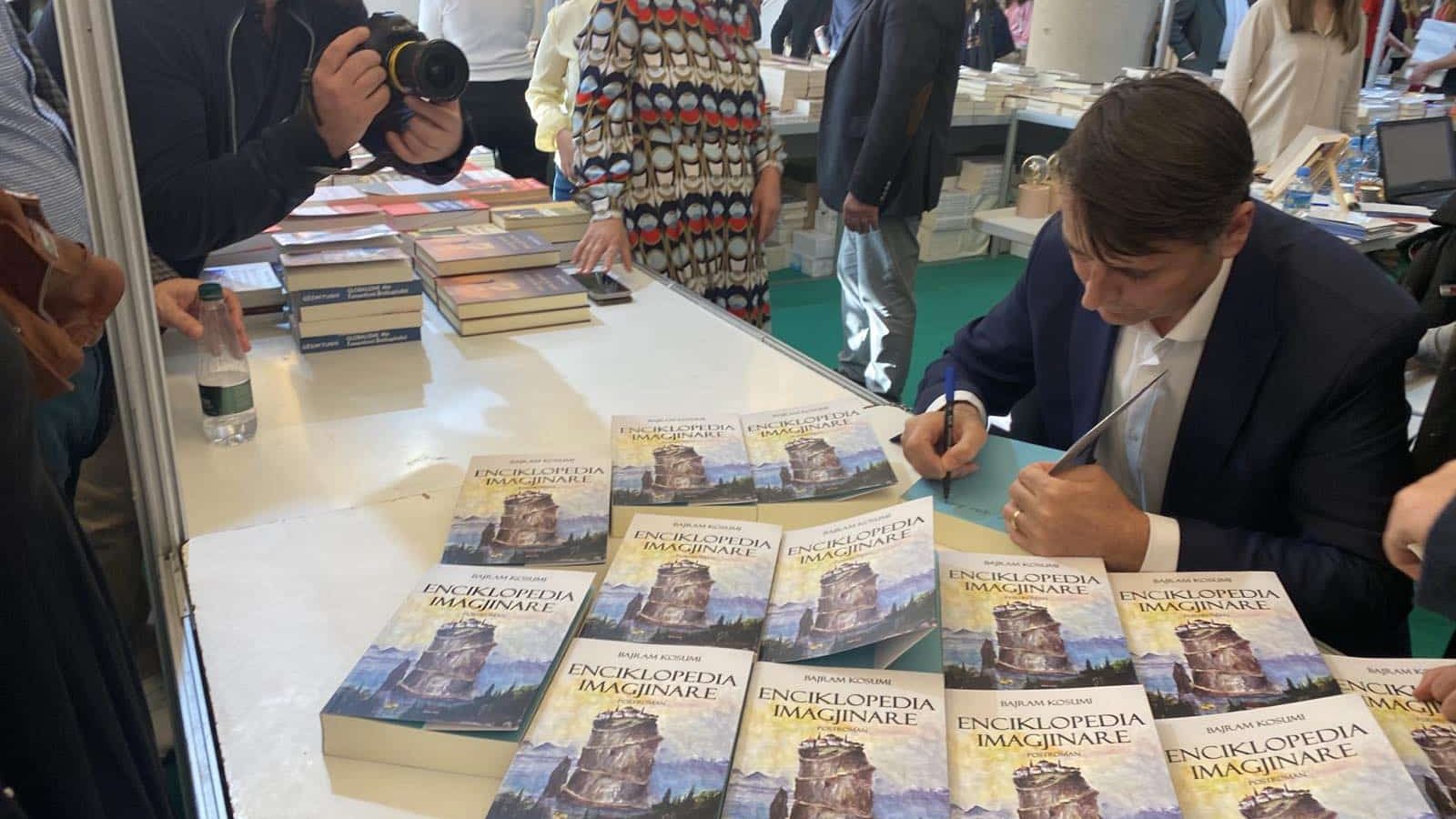

Kosumi describes his new book Imaginary Encyclopaedia as a “post-novel”, a work of literary imagination whose stories and characters come from several different time periods, start from a historical background and end up in an imaginary reality.

He explained that he chose to write the book as an encyclopaedia because the classic novelistic form is going through a crisis.

“Virtual life has changed people’s lives to such an extent that no reader now can spare two months to sit and read, for example, Tolstoy’s War and Peace,” he said.

“Therefore I used this form of an encyclopaedia, in which does it not matter how voluminous it is. You can start reading it today, finish a part or two or three… then one week later you can reopen the book and continue. All the parts of the book are independent from the others,” he added.

He said he experimented with using elements of the novel, story and essay, and that the book has more than 500 characters and no single line of continuity running through it.

“The book is not about a single event or story. This is not a novel, it’s beyond the novel,” he asserted.

He said that he has worked on the book everywhere he has worked or travelled to since he was in prison in the 1980s and never stopped adding to it until it was published last month.

For Kosumi, the book exemplifies the idea of freedom that he could only imagine when he was behind bars.

“Imagination has no boundaries. If I didn’t have imagination and an ideal of freedom, maybe I wouldn’t have been in Nis prison in 1985. That generation [of student protesters] imagined freedom, they had Kosovo’s freedom as a vision,” he said.

“Maybe they didn’t have that vision in detail; I didn’t have that either. But we were certain that the truth will prevail, freedom will win out over ultra-nationalist and fascist-dominated theories. I’ve always believed that.”