Hypertension is a major global risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and mortality, with a high proportion of premature CVD deaths occurring in Asia [1]. Sodium (Na) and potassium (K) intake are key modifiable factors influencing blood pressure (BP) [2]. Excess Na intake exacerbates hypertension through fluid retention and impaired vascular function, while dietary K lowers BP by enhancing Na excretion and promoting vasodilation. Recent research emphasizes dietary pattern analysis, considering overall diet quality and interrelationships between foods and nutrients [3]. Traditional Asian diets, rich in plant-based foods and low in processed additives, highlight the need for region-specific dietary indices to address hypertension effectively.

As highlighted in the article by Wei et al. [4], dietary pattern analysis focuses on the overall health impact of diet rather than individual nutrients or foods. While specific nutrients and foods have been studied in relation to hypertension in Asian populations [5,6,7], there is still a gap in understanding the role of dietary diversity and food group intake in hypertension risk among Asian adults. The authors utilized data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) to explore the relationship between dietary diversity, food group intake, and the risk of new-onset hypertension among Chinese adults. The final sample included 11,118 participants (mean age: 41.3 years), with data from seven CHNS datasets spanning from 1997 to 2015. During a median follow-up period of 6 years, 3,867 individuals (34.8%) developed new-onset hypertension. The study outcome was new-onset hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg or diagnosed hypertension by physician or under antihypertensive treatment during the follow-up. The study aimed to evaluate the relationship between dietary diversity (measured by dietary diversity scores) and the quantity of food group intake with the incidence of hypertension in adults.

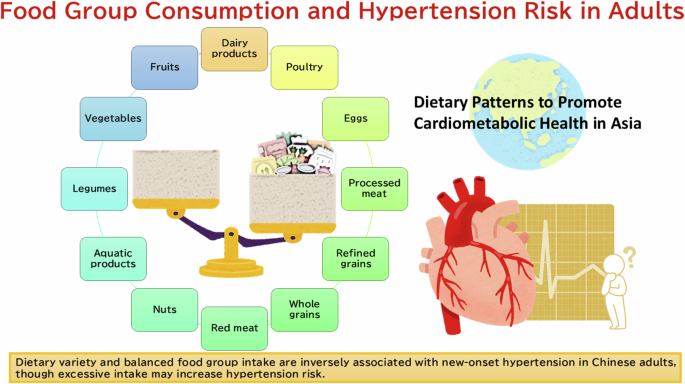

The study found a negative correlation between the cumulative average dietary diversity scores and new-onset hypertension. Specifically, participants with higher dietary diversity scores had a significantly lower risk of developing hypertension. An L-shaped association was observed between dietary diversity scores and hypertension risk. Participants in the second to fourth quartiles of dietary diversity scores had a lower risk of developing hypertension compared to those in the first quartile (HR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.59–0.69). Furthermore, the study identified the optimal intake ranges for various food groups, such as refined grains (346.7–375.0 g/day), vegetables (225.4–375.3 g/day), dairy products (16.7–60.0 g/day), and aquatic products (2.8–8.3 g/day), which were associated with a lower risk of hypertension. A plateau effect was observed for fruit, beans, and eggs, where consumption above certain thresholds (12.7 g of fruits, 16.1 g of legumes, and 8.3 g of eggs per day) did not further reduce the risk of hypertension.

The study used a large dataset of 11,118 adults with 6 years of follow-up, providing a robust basis for examining the long-term impact of dietary diversity on hypertension risk. The data spans several regions in China, capturing the diversity of dietary patterns across the country. The study provides concrete recommendations for the optimal intake of various food groups to minimize hypertension risk. This level of detail is a strength, offering actionable insights for public health policies and individual dietary adjustments. The study is the first to demonstrate the link between greater dietary diversity and a lower risk of developing hypertension. By focusing on the broader dietary pattern rather than isolated nutrients, the research supports the idea that a varied diet may be crucial for hypertension prevention. By supporting the concept of “dietary diversity,” the findings align with current dietary guidelines and provide evidence to inform public health strategies aimed at reducing hypertension [8].

However, there are some limitations. The dietary data was self-reported, which can lead to misclassification and recall bias. The accuracy of food intake reporting is often limited, which could affect the reliability of the findings, particularly if participants underreport or overreport their intake. As an observational study, it cannot establish causality. While the study shows an association between dietary diversity and reduced hypertension risk, it does not prove that higher dietary diversity directly causes lower hypertension risk. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm this causal relationship.

The study was conducted on a Chinese population, and its results may not be directly applicable to other countries with different dietary patterns and cultural contexts. For example, dietary habits in Western countries, where food types and processing methods differ, might not exhibit the same relationships with hypertension. The median follow-up period of 6 years is relatively short for studying chronic conditions like hypertension. Longer-term studies would provide more comprehensive insights into the lasting effects of dietary diversity on hypertension risk.

This study is the first to show that greater diversity in food group intake is significantly associated with a lower risk of new-onset hypertension in general Chinese adults. It supports the idea that promoting dietary diversity can be an effective strategy for hypertension prevention. The study also identified optimal intake ranges for various food groups, offering practical guidance for dietary modifications. The 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health by the American Heart Association emphasizes the strong link between poor diet quality and the elevated risk of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality [9]. It advocates for focusing on dietary patterns rather than individual foods or nutrients, recognizing the importance of nutrition from early life. The statement outlines key elements of heart-healthy dietary patterns and identifies structural challenges that hinder adherence to these patterns. Key recommendations for promoting cardiometabolic health include: (1) adjust energy intake and expenditure to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight; (2) eat plenty and a variety of fruits and vegetables; (3) choose whole grain foods and products; (4) choose healthy sources of protein (mostly plants; regular intake of fish and seafood; low-fat or fat-free dairy products; and if meat or poultry is desired, choose lean cuts and unprocessed forms); (5) use liquid plant oils rather than tropical oils and partially hydrogenated fats; (6) choose minimally processed foods instead of ultra-processed foods; (7) minimize the intake of beverages and foods with added sugars; (8) choose and prepare foods with little or no salt; (9) if you do not drink alcohol, do not start; if you choose to drink alcohol, limit intake; and (10) adhere to this guidance regardless of where food is prepared or consumed. The statement also highlights challenges like marketing unhealthy foods, food insecurity, and structural racism that hinder adherence to heart-healthy diets. It calls for public health efforts to create environments that make it easier for individuals to follow these dietary patterns. Additionally, studies in other populations with different dietary patterns and longer follow-up periods would help determine whether these findings can be generalized beyond the Chinese context.

References

-

Zhao D. Epidemiological features of cardiovascular disease in Asia. JACC. Asia. 2021;15:1–13.

-

Hisamatsu T, Kogure M, Tabara Y, Hozawa A, Sakima A, Tsuchihashi T, et al. Practical use and target value of urine sodium-to-potassium ratio in assessment of hypertension risk for Japanese: Consensus Statement by the Japanese Society of Hypertension Working Group on Urine Sodium-to-Potassium Ratio. Hypertens Res. 2024;47:3288–302.

Google Scholar

-

Lim GH, Neelakantan N, Lee YQ, Park SH, Kor ZH, van Dam RM, et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular diseases in asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2024;15:100249.

Google Scholar

-

Wei Y, Su X, Wang G, Zu C, Meng Q, Zhang Y, et al. Quantity and variety of food groups consumption and the risk of hypertension in adults: a prospective cohort study. Hypertens Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-02036-4. Online ahead of print.

-

Liu M, Zhou C, Zhang Z, Li Q, He P, Zhang Y, et al. Inverse association between riboflavin intake and new-onset hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76:1709–16.

Google Scholar

-

Zhang Z, Liu M, Zhou C, He P, Zhang Y, Li H, et al. Evaluation of dietary niacin and new-onset hypertension among Chinese adults. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:e2031669.

Google Scholar

-

He P, Li H, Liu C, Liu M, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, et al. U-shaped association between dietary copper intake and new-onset hypertension. Clinical Nutrition. 2022;41:536–42.

Google Scholar

-

2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, Dietary Patterns Subcommittee. Dietary patterns and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020.

-

Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Vadiveloo M, Hu FB, Kris-Etherton PM, Rebholz CM, et al. 2021 Dietary guidance to improve cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144:e472–e487.

Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Minegishi, S. Dietary diversity and its association with hypertension risk: insights from the China health and nutrition survey.

Hypertens Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-025-02119-w

-

Received: 24 December 2024

-

Revised: 30 December 2024

-

Accepted: 30 December 2024

-

Published: 16 January 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-025-02119-w

Keywords

- Dietary variety

- Quantity

- Food groups

- Hypertension