It is a moment for quiet art in London: Hiroshige’s floating world at the British Museum, Victor Hugo’s shadowy drawings at the Royal Academy, the National Gallery’s Sienese devotional paintings, and now a pair of meditative, beguiling sculpture shows where in unexpected materials — rubbed graphite, coloured thread and polyester, soot and smoke — two lesser-known artists seek visual equivalents for the haze of memory and the absences of dislocation. These are common enough contemporary themes, but Do Ho Suh: Walk the House at Tate Modern and the Estorick Collection’s Claudio Parmiggiani are original, hushed and lovely small exhibitions, at once making the familiar strange and transporting you to strange, silent places.

A tremulously graceful paper house, a life-size model of the traditional Korean timber hanok with tiled curved roof, is the charming opening to Do Ho Suh’s exhibition. It represents — or, more accurately, carries the traces of — Suh’s childhood home: the artist wrapped the exterior in mulberry paper, laboriously rubbed it over with graphite to reveal surfaces and textures — wood panelling, latticework doors, decorative scrolls, intricate carving — and left it for nine months, then peeled off the paper frame and erected it on aluminium posts.

Alluding to its intimacy, this is called “Rubbing/Loving: Seoul Home” (2013-22) and is the most perfect example of Suh’s method of recreating architecture as a ghostly imprint. He compares getting the right touch — too soft and you don’t get an impression, too hard and you obliterate it — to caressing a body; there is also a connection to his initial training in eastern ink painting where, he says, “each mark is like the equivalent of a breath”.

The hanok is the image which has filled Suh’s mind since, as a homesick student in Providence, Rhode Island, in the 1990s, he dreamt that such a house flew across the Pacific, trailing a parachute, and crashed into the 19th-century American apartment building where he was lodging. Walk the House refers to an old Korean practice of deconstructing and reassembling the hanok in a new site, literally making it walk, and to this particular building’s march through Suh’s art.

In “Home Within Home” (2015), the dream is made material in a 1:9 scale resin replica of the hanok, transplanted within the American building; Suh measured and scanned the dwellings in 3D, then shrank and combined them. In the large work on paper “Haunting Home” (2019) the hanok levitates mid-air, attached like a kite to cascades of multicoloured threads held by a man running on the ground. So nostalgia pulls Suh along.

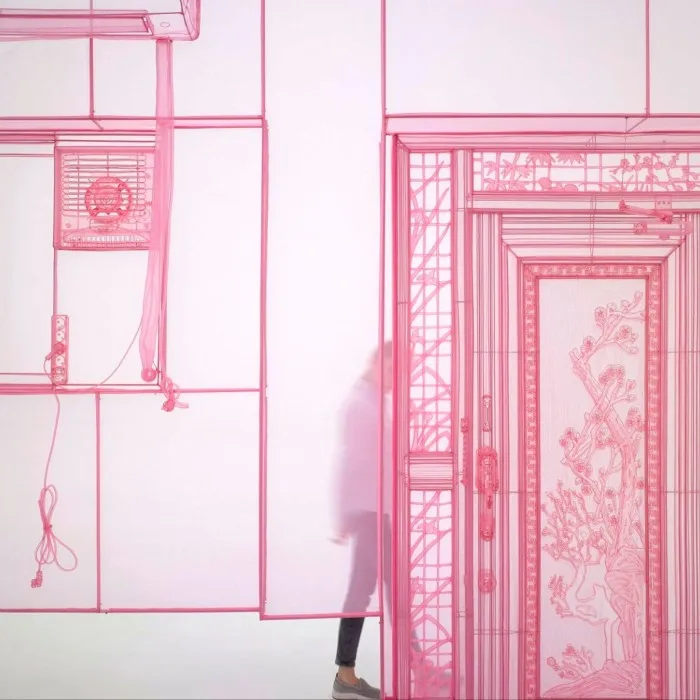

The hanok was an echo of the past even when Suh’s father had one built, based on a 19th-century example in the imperial palace, for his family in the 1970s — a time of massive postwar expansion in Seoul, when sleek high rises began to soar. Today, tiny hanok villages are tourist attractions nestled among Seoul’s geometric glass and metal cityscape; Suh conveys something of that incongruity by placing his paper house alongside the bright, modern “Nest/s” (2024), a long rectangular space recreating in translucent multicoloured polyester fabric some of the thresholds, corridors and doorways from Suh’s former homes in New York, London, Berlin and Seoul.

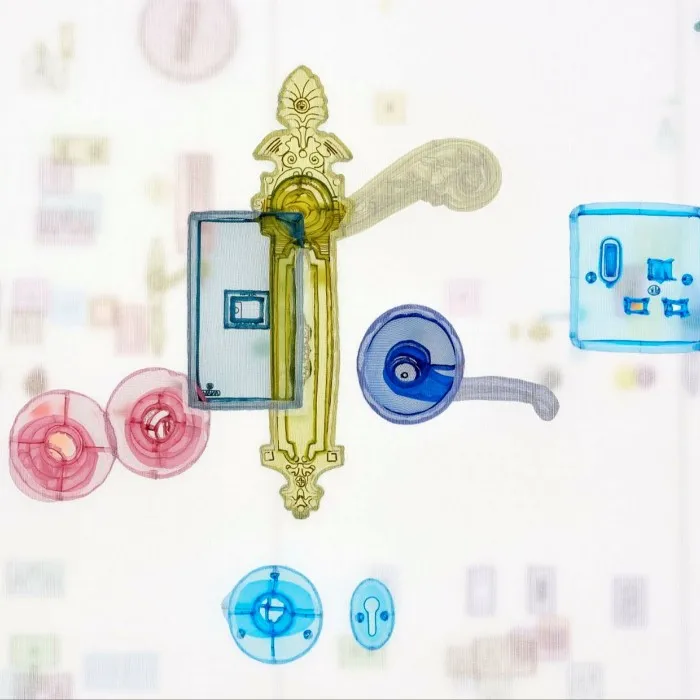

Linking separate places and times, these transitional spaces form a continuous passage, the flimsy diaphanous material according with the instability of stream-of-consciousness recollection. You enter to discover meticulously stitched, eerily exact fabric versions of extractor fans, dangling wires, fire extinguishers, a Korean ink-painted panel. The walk-in white cube of “Perfect Home” (2024), its interior sewn with light switches, doorknobs, electric plugs, colour-coded according to their remembered location from Suh’s peripatetic life, is a minimalist variant.

Suh is on the one hand so simple, making us all think how we carry the stamp of past homes, and on the other a romantic conceptualist, considering ruins and displacement, pushing towards dissolution. “I’ve literally dreamt, of making something out of smoke — out of nothingness,” he says.

This is what Claudio Parmiggiani has been doing since 1970 in his “Delocazione” series: white shadows of everyday objects created by arranging the items against wooden panels which are exposed to fire from burning tyres for days; when cooled, with the soot settled, phantoms of the originals remain in the traces drawn by the smoke.

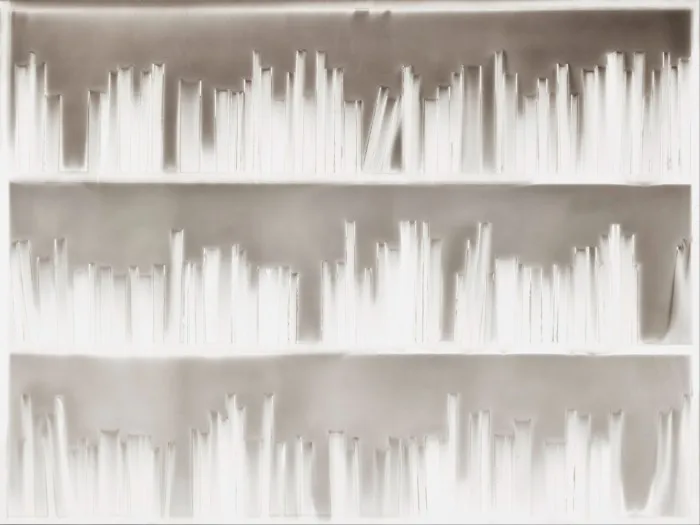

In the Estorick’s first gallery, two mirage-like reliefs formed as grids face each other: bottles and vases of varying decorative shapes and dimensions — as a teenager Parmiggiani was an assistant to Giorgio Morandi — and rows of books, each lined up on layers of shelves, their remnants evoking vanished libraries, disappearing civilisations. Standing between these evocations of negative space in blistering white light feels like being absorbed into a photogram.

Parmiggiani’s inspiration was the instant when, in the basement of Modena’s Galleria Civica, he moved a painting and ladder and discovered their silhouettes as dust outlines on the wall. He set out to show presence as absence, “the imprint on the walls of everything that had been there, shadows of the things that these places had contained”. His images are delicate and vulnerable, charged with the heat and violence of their making, as if Morandi’s stillness is crossed with Alberto Burri’s torched canvases.

Jagged shards of broken glass in window panes create elegant abstract patterns, a tiny spiral fossil of a nautilus shell is crystalline yet spectral, and in “Shadow Sculpture” (1999), a stone statue abandoned to fire becomes a forlorn distorted human silhouette, “like an extinguished light that lights a soul in the dark,” says Parmiggiani. The chance of soot contours here left the illusion of smoky grey wings, suggesting a fallen angel.

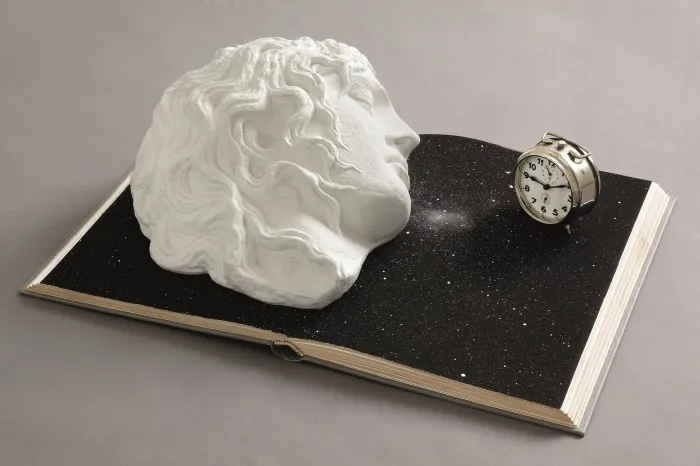

Three-dimensional pieces swell the elegiac theme: the pigment-splattered plaster cast and unlit oil lamp “With Extinguished Light” (1985); a mise-en-scène of a clock, white plaster head and black book (2009); a knife plunged into a lead cast of an ear and a paperback by philosopher Elémire Zolla entitled “What is Tradition?” (1997). Shipwrecks — a charred model boat with soot-marked sails, jutting out to collide with us as we approach (1971); the upended wooden fragment of a vessel (2019) — are recurring motifs.

This is Parmiggiani’s first institutional British show and an ideal introduction: the artist, born in Luzzara in 1943, connects in his humble materials to his Arte Povera contemporaries, but also to the earlier 20th-century Italian metaphysical tradition embraced by artists prominent in the Estorick’s marvellous collection, including Giorgio de Chirico, Ardengo Soffici, Marino Marini. In his own economical language, Parmiggiani continues their themes of transience, the fragility and endurance of memory, asking what remains of cultures, stories, ourselves, in the beauty of traces left by dust and time.

Tate Modern to October 19, tate.org.uk; Estorick Collection to August 31, estorickcollection.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning