While naturalists have a symmetry view on health and disease, they in general hold that neither of the concepts have any moral appeal. Normativists on the other hand agree that both concepts are value laden and have a moral appeal, but they cannot agree on whether the appeal is symmetrical or not. For all parties, it is difficult to demonstrate what it is with health and disease that makes them similar or different (and how) in order to spur a difference in moral appeal. From a pluralist point of view, the arguments for an asymmetry view appear more compelling than the symmetry view. There are many more (and different) arguments for the difference in health and disease being morally relevant for a moral appeal. Without confusing quantity with quality, there are several good reasons to claim that there is a stronger moral appeal from people’s disease than from their health.

It is important to underscore that this is a general claim, as I have not investigated whether there is a difference in a specific type of moral appeal from a particular conception of health and a certain conception of disease. Specific studies of particular kinds of moral appeal (such as moral imperative) from certain conceptions of health and disease are of course needed and welcome but are beyond the scope of this study.

One highly justified objection is that the study addresses disease and not illness (in terms of negative first-person experience) as illness is more directly related to pain and suffering. There are two main reasons for this. First, illness does not have a clear counterpart, as health is much broader than the absence of illness. Second, illness is much broader than what we can expect to be morally responsible for. We cannot be responsible for all people’s negative first-person experiences — especially not in the health care or health policy setting.

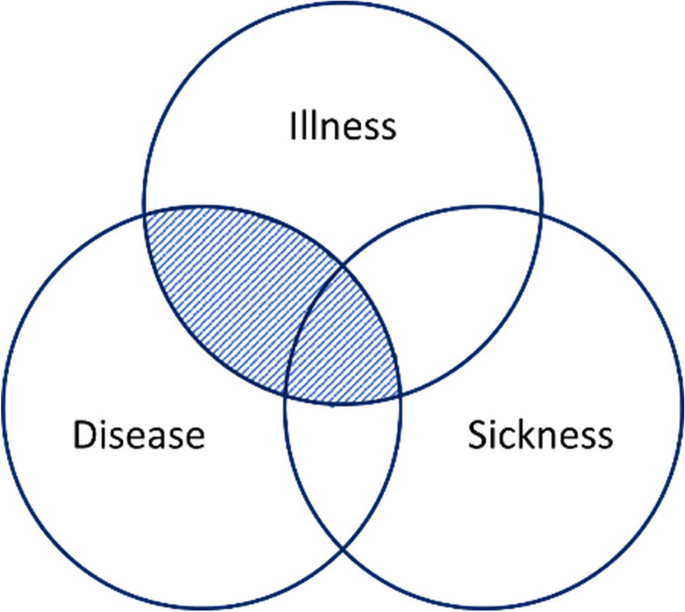

In the context of health professionals, healthcare systems, and health policy, we can only be expected to have moral obligations towards those parts of people’s negative first-person experiences that are related to disease. A person may suffer from a wide range of external factors, such as poverty. However, these types of suffering are beyond the subject matter of healthcare. Healthcare can only be responsible for those parts of suffering (and illness) that fall under its subject matter, i.e., where one can provide physical, biochemical, biomolecular, or mental characteristics of the condition that is thought to cause or make up the suffering (disease) and potentially can reduce the suffering. Ought implies can [47]. Figure 2 tries to illustrate the area that is addressed in this study. The reason why the area of disease, but not illness or sickness, is not included, is that it is not directly related to pain or suffering.

The area of human malady (disease, illness, sickness) that is discussed in this article. See also [48]

Moreover, if one defines health as the absence of disease and conversely, the moral appeal should be symmetrical. However, this ideal model is difficult to defend [42]. While health and disease are interdependent, they are neither mutually exclusive nor exhaustive. You can be both healthy and diseased as well as neither healthy nor diseased. For details, see [42]. Moreover, it may be argued that it is more fruitful to discuss the (a)symmetry of wellbeing and suffering than that of health and disease. However, as we classify and attribute rights to disease and not suffering, it seems warranted to focus on health and disease.

In general, if there is a stronger moral appeal from disease than from health, this has substantial implications, both for patients, professionals, health policy makers, and society at large.

Implications

First, it has implications for the ethos of medicine, i.e., its values and goals. It means that health professionals, health policy makers, as well as society at large have to give priority to disease demotion over health promotion. Treating persons suffering from malaria or cancer here and now should have priority before screening healthy persons for (vague) indicators of potential future disease and before enhancing the health and wellbeing of people. While radical, the moral primacy of disease is not new for defining the goals of medicine and health care [13, 49, 50].

Second, it specifically implies that there is a stronger personal, professional, and social obligation towards persons with a disease than persons in (good) health. Within a healthcare setting, both treatment and palliation of manifest disease should then have higher priority than disease prevention, which in turn should have higher priority than health promotion. This radically opposes the maxim that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” [5, 7].

Third, the asymmetry in moral appeal also has implications for which medical providers (specialties), which patient groups, and which countries/regions deserve more resources and attention. Those patient groups, specialties, or countries/regions with the highest burden of disease should have the most resources.

Fourth, the asymmetry has implications for the enhancement-treatment debate [51], where it implies that the treatment of disease has priority before the enhancement of health. However, first and foremost, it challenges the general assumption of symmetries between wellbeing and suffering as well as between health and disease.

Fifth, healthcare (or more precisely, disease care) should have priority over other services directed at improving people’s health and wellbeing. That is of course not to say that such services should have no priority. So far, nothing has been said about the strength of moral appeal or the extent of asymmetry. This is the topic of one or more separate studies. However, some preliminary notes can be made.

The various theories and positions studied above give different answers to the relationship in the moral appeal from health and disease. Figure 3 illustrates the relationship for some of the discussed perspectives.

Relationship between severity of disease versus strength of health and the strength of moral appeal. a Utilitarian (symmetrical) account, b negative utilitarian (asymmetrical) account, c one example of an eliminativist account (where health has no moral appeal as it does not exist)

Limitations

There are certainly many limitations to this study.

First, it may be argued that medicine has a wide range of activities beyond the categories of health and disease that then are not covered by this analysis, e.g., vasectomy and tubal ligation. However, health and disease are basic concepts of medicine’s goal related to its basic moral appeal.

Second, the asymmetry in moral appeal could as well be discussed in terms of prioritarianism, where those suffering are worse off than those who are well. However, this is a slightly different study.

Third, as noted at the outset, the study has not scrutinized specific conceptions of health and disease. Only general normativistic and naturalistic conceptions have been investigated. Further and more detailed studies are surely most welcomed.

Classical utilitarians may argue that it is not the number of arguments for an (a)symmetry in moral appeal that counts, but the quality of the argument for symmetry. However, both sides of the (a)symmetry divide have problems in explaining what with health and disease that provides a (difference in) moral appeal. There may of course be differences in how compelling one finds that arguments on both sides.

Fifth, there are certainly many perspectives that have not been addressed. For example one can argue for an (a)symmetry from a rights-based perspective: “disease and disability become the object of concern in Western society because they are seen as a threat to equal opportunity, and in turn to the moral foundation of economic life” [52]. Or from a pragmatic point of view that it is much more resource demanding to improve a person’s health than to reduce a person’s disease. Moreover, various biases may also account for the moral relevance of health and disease, e.g., loss aversion according to which a loss is considered as more negative than an equivalent gain (of wellbeing).

Sixth, it can be argued that health and disease are constituted by other phenomena than wellbeing and suffering, for example by disability or harm [53,54,55]. While this is true, wellbeing is widely used to define the concept of health as an expressed goal of healthcare [56,57,58,59]. The same goes for suffering [60,61,62,63,64,65].

Seventh, it may be argued that suffering and wellbeing can be defined and measured in many ways [66,67,68,69], that they are implicit negations, or that suffering is not bad or wellbeing or happiness is not good [70]. This is clearly true, and as pointed out, it must be studied in relation to explicit conceptions of health and disease.

Eight, this study has not differentiated between different categories of moral appeal, for example between types of moral actions and obligations, such as (a) perfect obligations, which require compliance without exception; (b) imperfect obligations, which allow for discretion with respect to their fulfillment; and (c) supererogatory actions, which are very highly regarded from a moral point of view but not morally required [71, 72]. Again, this needs much more elaboration than allowed within the scope of this study.

Ninth, due to limited space and scope the study has not taken important temporal aspects into account. For example, consequentialism (and other presented positions) have developed over time which can provide important nuances. However, I have referred to “classical consequentialism” and other specific positions. More detailed elaborations on the development of the various positions are warranted and welcomed. Moreover, the important trade-off between disease treatment here and now having consequences in the far future versus health-promoting measures having consequences in the near future [73] have not been addressed either, as this warrants a separate study. Such a study would need to take into account both present and future (potential) harms and benefits related to present and future resource allocation related both to health and disease.