A man tries to cool down during a heatwave in Mexico in 2023.Credit: Victor Medina/Reuters

The final numbers are in, and 2023 is officially the hottest year on record — shattering previous records, as well as the expectations of many climate scientists. And researchers say that 2024 could be even worse.

Global temperatures this month, particularly in the oceans, are well above average for the time of year. The ongoing El Niño weather pattern — in which warm water pushes into the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean — is also entering its second year, a time when it typically supercharges global warming. These and other factors suggest that 2024 could see even more extreme weather and climate impacts than 2023, as humans continue to pour heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

“We know 2024 will have heatwaves,” says Samantha Burgess, deputy director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in Reading, UK. But “when and where they occur we can’t predict”.

Overshooting a threshold

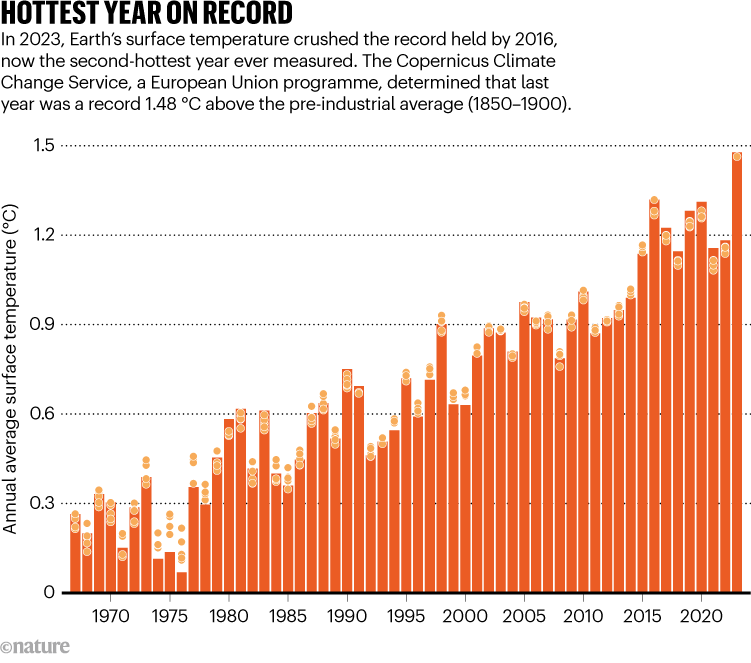

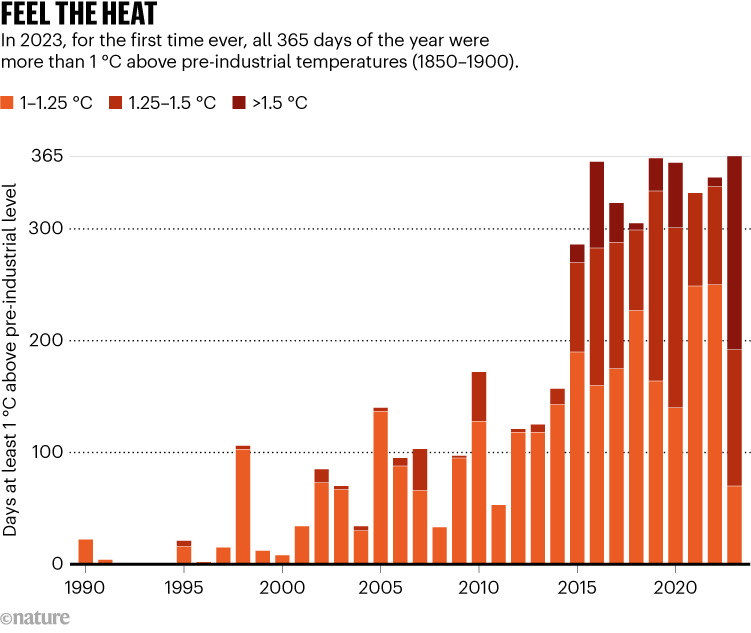

According to figures released this week by various services, global average surface temperatures in 2023 were 1.34–1.54 °C above the average for 1850–1900 — a ‘pre-industrial’ period before human activities kicked into high gear (see ‘Hottest year on record’). “The findings are astounding,” says Sarah Kapnick, chief scientist for the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Washington DC. According to the Copernicus service, every day last year was at least 1 °C warmer than the pre-industrial average, the first time that has ever been recorded.

Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service/European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

The precise estimates vary according to the data sets used, but all the analyses conclude that the global average annual temperature was near or above the 1.5 °C limit that countries pledged to try to avoid in the 2015 Paris climate accord, to help prevent the worst impacts of climate change. The world now seems poised to overshoot that threshold: nearly half of the days in 2023 were more than 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial average, according to the Copernicus data, and two days in November exceeded a 2 °C increase (see ‘Feel the heat’).

The Met Office, the United Kingdom’s national weather service based in Exeter, is predicting that, in 2024, there is a good chance of the global average surface temperature passing the 1.5 °C mark. (The Met Office analysis has 2023 as 1.46 °C above the pre-industrial average.) “It is the first time we are forecasting” this, says Nick Dunstone, a climate scientist at the Met Office who led the work. Passing 1.5 °C for one year does not mean that the Paris agreement has officially been violated, however: researchers say that the threshold needs to be surpassed for one or more decades to have formally breached the limit.

But the extreme climate and weather impacts of 2023 underscore how humanity has fundamentally altered the planet. “This is only a preview of what is to come if we do not act now,” says Ruth Cerezo Mota, a climate scientist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mérida, Mexico.

Shattering records

Various climate data services agree that 2023 saw the hottest day on record (6 July), the hottest month on record (July) and the hottest-ever June, July, August, September, October, November and December on record. When researchers combine modern temperature records with palaeoclimatic proxies of past temperatures, they find that 2023 is probably the hottest in at least 100,000 years.

Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service/European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

Many factors contributed to the 2023 extremes, Burgess says. These include the greenhouse gases humanity has been releasing into the atmosphere — 2023 saw all-time high emissions of 36.8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels — as well as unusually warm oceans. The 2022 eruption of a volcano in Tonga, which injected heat-trapping water vapour into the atmosphere, was also a factor. And changes to maritime shipping regulations in 2020 that cut the amount of sulfur dioxide pollution emitted into the atmosphere played a part; although sulfur dioxide particles harm human health, they can also have a cooling effect on the climate.

Is it too late to keep global warming below 1.5 °C? The challenge in 7 charts

Another player is the El Niño, which arose unusually quickly in mid-2023. Modelling suggests that the planet is now at or near the peak of the El Niño. The current high heat content of the global ocean will probably feed marine heatwaves in the coming months, Burgess says.

Researchers are still working to determine whether the extreme temperatures of 2023 are a sign that global warming is accelerating, or are, in part, a fluctuation attributable to natural variability in the global climate system. Former NASA climate scientist Jim Hansen, who warned the world about the dangers of climate change in the 1980s, has suggested that an increase in trapped solar energy on Earth is leading to faster rates of global warming. But other researchers aren’t so sure. “Watching the climate for the next few years will tell us if we broke it or not,” says Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University in College Station.

The temperature surge that began in June 2023, before the El Niño took hold, was fuelled partly by natural variability in the North Atlantic Ocean and other regions, according to Berkeley Earth, a non-profit research organization in Berkeley, California. That team predicts a 58% chance that this year will be warmer than last year, and that 2024 will almost certainly be the hottest or second-hottest year on record.

The future is already here

However this year plays out, it will certainly come with more of the “heartbreaking” impacts seen in 2023, Cerezo Mota says.

Spurred by climate change, the extreme weather of 2023 included category-5 Hurricane Otis, which slammed into the Mexican city of Acapulco, killing dozens of people. Wildfires in Quebec, Canada, in June and July poured smoke across major cities, including many in the midwestern and northeastern United States. Blazes raged across Greece in July and August, incinerating forests and killing a number of people. And on the Hawaiian island of Maui in August, a wildfire driven by high winds and invasive grasses killed at least 100 people.

Record wildfires ravaged Quebec in Canada last year.Credit: Frederic Chouinard/SOPFEU/Anadolu Agency via Getty

Heatwaves also baked many parts of the world, with China recording its highest temperature ever and Phoenix, Arizona, experiencing 31 consecutive days at 43 °C (110 °F) or above. In Mexico, more than 200 people died in a heatwave in July, and a three-year drought in East Africa, exacerbated by climate change, has led to food insecurity and refugee movements.

By the end of the year, global leaders at COP28, the United Nations climate summit held in Dubai, had agreed for the first time to transition away from using fossil fuels for energy — a move that many say is too little, too late.

“The future scenarios of climate change are already here,” says Tereza Cavazos, a climate scientist at the Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education of Ensenada in Mexico. “We do not need to wait 15 or 20 years more to see the changes and impacts that were expected far into the future.”