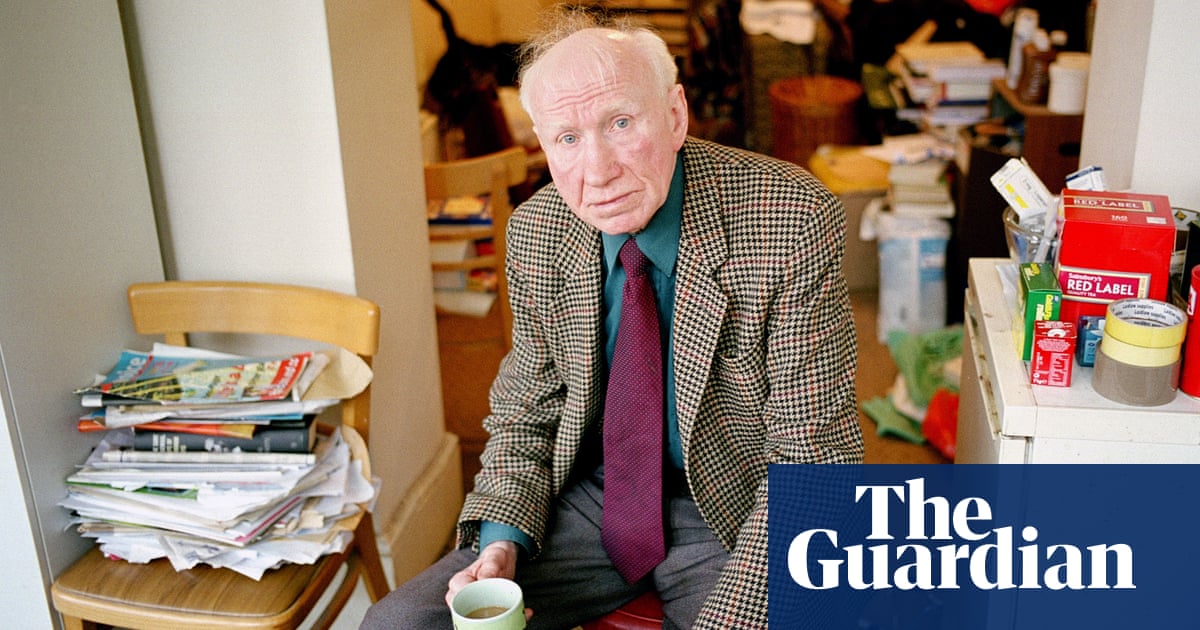

Eddie Linden, who has died aged 88, was the editor of the poetry magazine Aquarius, the author of two books of poems, and the subject of a biography. Yet there has seldom been a less likely literary figure.

Abandonment stalked Eddie throughout his life, together with Catholic guilt – not least over his homosexuality – and the challenge of semi-literacy. In spite of being rejected at birth by his unmarried mother in Northern Ireland, and the cruelty of those charged with his care in Scotland, he retained an intrinsic decency, which he held to as a precious possession. In the mid- 1960s, by which time he had settled in London, he began to forge a path in the literary world.

The first issue of Aquarius appeared in 1969 and after that Eddie could travel further in this new land, requesting and receiving poems from writers such as Seamus Heaney and Derek Mahon, establishing friendships as he went.

Aquarius endured for 18 years, helpfully supported by figures such as George Barker and John Heath-Stubbs. The issues were often overseen by a guest editor, but the top line was “Editor: Eddie S Linden”. No actor seeing their name in lights ever felt more proud. His first collection, City of Razors, was published in 1980. The title poem became something of a classic. It was followed in 2011 by a selected poems, A Thorn in the Flesh.

He was born Sean Edward Glackin, in Coalisland, County Tyrone. To avoid disgrace, his mother placed him in the care of relatives in Bellshill, Lanarkshire. He took the name of his foster father, Eddie Linden, later the subject of the poem The Miner, which was one of Eddie’s favourites at public recitals. His poems were stored in memory and spoken aloud in bardic manner, with eyes closed and chin raised, while pacing the floor. The effect was mesmerising.

When the mood took him, he could describe his early childhood as happy, but the bare facts are grim. His foster mother died when he was nine and, as Eddie told me some years ago in the preparation of a profile for the Guardian: “In 1945 my father remarried and from then on my life became hell. His new wife didn’t want me.”

An experimental reunion with his birth mother, now living in Glasgow, resulted in further rejection – he had been left on her doorstep by the new wife – and the next four years were spent in an orphanage in Lanark run by the Sisters of Charity. Eddie carried many bleak memories in his head, but few worse than that of “the big black car that came to take me away”.

The biography by Sebastian Barker, son of George, was published in 1979 under the title Who Is Eddie Linden. (The omission of a question mark became a topic of debate: a simple error or a stylistic device with existential undertones?) Eddie did not agree with everything said about him in the book, but it is only fair to the younger Barker to say that Eddie had a habit of finding things to disagree about.

Alcohol played a part in these tantrums, which often resulted in remorse. When he related the tale of how he insulted the wife of the Scottish poet Sydney Goodsir Smith in an Edinburgh pub, and that “she hit me over the head with her handbag”, it was easy to laugh but impossible not to notice the profound mortification – even though the incident had taken place 40 years earlier.

Eventually, he got the better of the bottle, and while his actions could still be unpredictable, his raw, childlike nature was more likely to show through, into his seventies and beyond. As Sebastian Barker once said: “Eddie notices everything.”

There were staging posts along the route to a different world. One was the Young Communist League, which he joined in Scotland while in his teens. “At that time, the Communist party had education classes,” he said. “Not just in Marxism, but in Dickens, in Shakespeare – and that was a discovery for me. Then there was the Workers’ Educational Association. This was my way of getting away from that life.” Receipt of a bursary enabled a year’s residence at Plater College, a Catholic establishment in Oxford.

Aquarius was the greatest event of all. It was launched with £70 saved up from his job as a library porter. With his ability to be completely himself in the presence of talent and social standing – condescension was the one reaction he could not forgive – Eddie endeared himself to some of the leading figures of the period. Not only Barker and Heaney, but Peter Porter, WS Graham – who liked to have Eddie shave him – Norman MacCaig and Goodsir Smith, whose wife had wielded the handbag. The great Glaswegian all-rounder Alasdair Gray was one of many who made portraits.

All contributed to Aquarius, as did Margaret Atwood, Elizabeth Smart and Douglas Dunn. Scottish, Irish and Australian poetry got special issues, along with women’s writing and the literature of the 40s. Ralph Steadman designed the cover of one issue of the magazine and portrayed Eddie in an abject pose on the jacket of Who Is Eddie Linden.

In 1995, a play inspired by Barker’s biography was staged at the Old Red Lion theatre in Islington, north London, with Michael Deacon in the role of the poet and editor. “It’s an exaggerated version of me,” Eddie told me after the show. Exaggerated? Impossible. I had thought it was an understatement.

It did not show what I thought of as the essential Eddie: a redeeming figure, battling with life on our behalf, confronting struggles most of us never have to face, emerging concussed but semi-victorious. The times when he came closest to answering the question Who Is Eddie Linden? were when a new issue of Aquarius had just come off the press.

He is survived by his cousins Julie and Geraldine.