Abstract

There is little research on anemia and vitamin D deficiency in HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) children. This study was aimed to describe and compare the prevalence of anemia and vitamin D inadequacy in HEU children and HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) children, and to examine the associations of HIV exposure with anemia and vitamin D inadequacy. This was a hospital-based descriptive cross-sectional study nested within the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV program in Hunan Province during July and September 2022. The HEU children aged 6 to 24 months were recruited from the PMTCT outpatient clinics located in five Municipal Maternal and Child Health Care Hospitals. The HUU children were recruited from routine child health examination clinics in the same five Hospitals. Questionnaires about children’s characteristics and maternal gestational conditions were collected from children’s caregivers, and blood samples were collected from all children. Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test, non-parametric rank sum test, and logistic regression were used for analysis. The study population included 336 HEU children and 334 HUU children. The overall prevalence of anemia in the HEU and HUU children was 10.4% and 8.1%, respectively. The median hemoglobin concentrations were 120 (115–126) g/L in the HEU children and 122 (116–129) g/L in the HUU children. Neither prevalence of anemia nor hemoglobin concentration was significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05). The prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in the HEU children (19.6% for deficiency and 25.0% for insufficiency) was significantly higher than that of the HUU children (11.4% for deficiency and 16.2% for insufficiency) (P < 0.001). The median 25(OH)D concentration in the HEU children was significantly lower than that of the HUU children (23.80 (13.50–34.08) vs. 32.08 (18.60–39.32) ng/ml) (P < 0.001). HIV exposure in HEU children was significantly associated with an increased risk of vitamin D deficiency (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.72, 95% CI: 1.13–2.61) and vitamin D insufficiency (AOR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.01–2.34), but not with anemia (AOR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.32–2.01). The PMTCT program shall strengthen vitamin D supplementation in HEU children and caregivers shall appropriately extend the outdoor activity time of HEU children to reduce the occurrence of vitamin D inadequacy.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus-exposed uninfected (HEU) children are HIV-negative children born to HIV-positive mothers1. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS demonstrates that more than 1 million HEU infants are born every year globally, with 90% in Africa, and 4% in Asia and the Pacific region2. China is located in eastern Asia and on the west coast of the Pacific Ocean. Despite the low HIV epidemic in China, the HIV prevalence among pregnant women remains at 0.1% or below3,4, lower than the global level (2.9%)5. However, as a populous country, more than 5000 HEU infants are born every year in China6. Hunan is a large province in central and southern China, and has an annual number of HEU infants higher than the average level of all 34 provinces7. Since 2011, the national program on Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV has been available freely in all counties of China with the support of National Health Committee, and integrates comprehensive measures for HIV screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up to enhance mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) prevention and control and improve the quality of new births8. As the national program of PMTCT of HIV was successfully implemented across China, the MTCT rate was gradually declining from 7.4% in 2011 to 3.6% in 20208.

The health problems of HEU children have attracted growing attention from researchers. Compared with the HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) children born to HIV-uninfected pregnant women, HEU children suffer from higher risks of development delay9,10, growth impairments11,12,13, undernutrition14,15 and death16. Nevertheless, there is little research on anemia and vitamin D deficiency in this subpopulation group. Anemia is a condition in which the number of red blood cells or the hemoglobin concentration in peripheral blood is lower than the normal level17. Anemia occurs when there is no enough hemoglobin in the body to carry oxygen to organs and tissues. World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia in children aged 6–59 months as a hemoglobin (Hb) concentration < 110 g/L at sea level18. Vitamin D is a fat-soluble essential vitamin obtained primarily through ultraviolent rays and plays a critical role in regulating bone metabolism, cell growth, immune and neuromuscular function. Vitamin D deficiency is defined as the 25-hydroxyvitamin-D (25(OH)D) concentration < 12 ng/ml19. Anemia and vitamin D deficiency are common health problems for children under 5 years of age, particularly infants and children under 2 years of age. Data from WHO showed that the global anemia prevalence among children aged 6–59 months was 39.8% in 2019, and maximized in Africa (60.2%)20. A systematic review showed that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among children under 5 years of age in South-East Asia ranged from 4.3–57.3%21. The anemia and vitamin D deficiency prevalence among children under 5 years of age in China were 21.2% and 10.8%, respectively22,23.

Anemia and vitamin D deficiency, as common nutritional diseases among children, will restrict child growth and development, and can cause irreversible damages to motional, cognitional and behavioral development24,25,26. At present, most related studies on anemia and vitamin D nutritional status in HIV-exposed children focus on HIV-infected children27,28,29, with HEU children as a socially comparator group30,31,32. Several cross-sectional studies have shown that anemia and vitamin D deficiency are common in HEU children, with the prevalence of anemia and vitamin D inadequacy (< 20 ng/ml) up to 14.4–53.6%30,32,33 and 34.6%34, respectively, but HUU children were not included as controls.

This study was aimed to describe and compare the prevalence of anemia and vitamin D inadequacy in HEU children and HUU children, and to examine the associations of HIV exposure with anemia and vitamin D inadequacy.

Methods

Study area

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study nested within the PMTCT of HIV program in Hunan Province. Since 2011, the PMTCT program supported by National Health Commission has been implemented in Hunan Province, and provides free comprehensive interventions for HIV-infected pregnant women and their children. It includes HIV testing and counseling, antiretroviral therapy, safe delivery for pregnant women, and prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, infection monitoring, scientific feeding guidance, growth and development monitoring for their children35. All HIV-infected pregnant women are given an antiretroviral therapy of AZT (azidothymidine) + 3TC (lamivudine) + LPV/RTV (lopinavir/ritonavir) or TDF (tenofovir) + 3TC + EFV (efavirenz) or TDF + 3TC + LPV/RTV during pregnancy. Those infants born by HIV-infected mothers are offered one daily dose of AZT up to 4 weeks postpartum for prophylactic antiretroviral therapy. All HEU children are fed with formula milk, and reasonably introduced with complementary food since 4–6 months of age according to Chinese Technical Specifications for Child Feeding and Nutrition Guidance36. In China, one province consists of several cities. Every city has a Municipal Maternal and Child Healthcare Hospital (MMCHH) established and maintained by the government. All HIV-infected pregnant women and their children are specially managed by local MMCHHs. Pregnant women are followed up from the confirmed HIV infection to 42 days after delivery, and their children are followed up from birth to 24 months of age. At the age of 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months, the children born to HIV-infected mothers are followed up by child health care doctors from local MMCHHs. Specifically, HIV infection status monitoring by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or HIV rapid antibody tests are done to timely determine the HIV infection status of children. Children are provided with scientific feeding guidance according to their growth and development conditions to ensure their healthy diet and adequate nutrition. Anthropometric measurements and nutritional status assessments for children are performed to find nutritional abnormalities and intervene in a timely manner. Hunan Province is composed of 14 cities, and thus has 14 MMCHHs. Given factors such as HIV epidemic among pregnant women, economic development level, and geographical location, five representative cities (Changsha, Hengyang, Loudi, Chenzhou, Huaihua) in Hunan were selected as the study area.

Study design and population

The subjects were HEU children and HUU children aged 6–24 months and their caregivers. The HEU children and their caregivers were recruited from the PMTCT outpatient clinics located in the MMCHHs in the above 5 cities during July and September 2022. These five MMCHHs were Changsha MMCHH, Hengyang MMCHH, Loudi MMCHH, Chenzhou MMCHH, and Huaihua MMCHH. The HUU children and their caregivers were recruited from routine child health examination clinics in the same five MMCHHs. The sample size was determined according to relevant equations for control studies based on an equal number of samples from the HEU children group and the HUU children group37. The equation for calculating sample size is as follows:

The prevalence rates of vitamin D deficiency in HEU children and HUU children were estimated to be 20% and 10% in the pilot survey, respectively. Together with the size of a test α (0.05), the size of a test β (0.10), and the non-response rate (20%), the final sample size for each group was determined to be 320 (= 266 × 1.2).

The inclusion criteria for children were as follows: (1) age 6 to 24 months; (2) non-infection with HIV; (3) single birth; (4) living in the local area for at least 6 months. The exclusion criteria for children were as follows: (1) HIV-infection or uncertain status of HIV infection; (2) congenital anomalies; (3) suffering from fever or diarrhea two weeks before enrolment; (4) multiple births; (5) lack of hemoglobin and 25(OH)D data; (6) refusal of children’s caregivers to participate in this study.

Data collection

The questionnaire survey was completed by child health care doctors who were selected from the five local MMCHHs. Prior to the survey, all the child health care doctors were trained unifiedly on study objectives, ethics, and data collection procedures, and only the qualified ones were allowed to take part in the questionnaire survey. All children’s caregivers participated in a standardized face-to-face interview conducted by child health care doctors. The questionnaire derived from the Chinese Work Specification for Prevention of HIV/AIDS, Syphilis and Hepatitis B Mother-to-Child Transmission was used to collect data from three aspects35: characteristics of children, characteristics of caregivers, and maternal gestational conditions. The characteristics of children included age, gender, ethnicity, birth gestational weeks, birth weight, and vitamin D supplementation. The characteristics of caregivers included type of caregivers, education level, and occupation. Maternal gestational conditions included moderate/ severe anemia and pregnancy comorbidity. A sample of peripheral blood from each child was taken at enrolment to evaluate hemoglobin (Hb) and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin-D (25(OH)D) concentrations.

Definitions of variables

Ethnic groups were divided into Han and minorities. Birth at < 37 gestational weeks was regarded as premature birth. The birth weight < 2500 g, 2500–3999 g, and ≥ 4000 g were considered as low birth weight, normal birth weight, and macrosomia, respectively. Vitamin D supplementation referred to the supplement of vitamin AD or vitamin D within the last month. Caregivers of children were those taking care of the diets, living and personal security of children and were divided into two types: parents, and grandparents/others. The education level of caregivers was classified into primary school or below (illiterate and semiliterate), junior high school, senior high school, and college or above. The occupation of caregivers was divided into houseworkers, government agency staff, business service staff and others. The hemoglobin concentrations in pregnant mothers with moderate anemia and with severe anemia were 70–99 g/L, and < 70 g/L respectively18. The maternal hemoglobin concentration referred to the third trimester of pregnancy and was obtained from the clinical medical records of maternal health handbook. Maternal pregnancy comorbidities included gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational hypertension, pregnancy associated with cardiac diseases, gestational liver diseases, and thyroid dysfunction.

Blood sampling and detection

About 2 ml of venous blood was collected from each child. Then 200 µl of the blood was put into an EDTA-K2 anticoagulant tube, which was gently inverted to make the blood uniform. Then 10 µl of anticoagulant whole blood was sucked using a capillary tube exclusive for hemoglobin, and sent to hemoglobin detection. Hemoglobin concentration was detected using a cyanide methemoglobin method. The remaining blood was placed indoor for 30 min and then centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 10 min to obtain the serum. The centrifugation radius was 200 px. Serum 25(OH)D was measured with an electrochemiluminescence method using a Roche Cobas e 601 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd., Germany)38.

Anemia and vitamin D nutrition status evaluation criteria

Anemia diagnostic criteria in children

According to WHO criteria, for children aged 6–59 months, anemia was defined at Hb < 110 g/L (100–109, 70–99, and < 70 g/L correspond to mild, moderate and severe anemia respectively)18. The hemoglobin levels in children living in different altitudes were calibrated according to Chinese anemia screening standard39, and cases from altitudes < 1000 m needed no calibration. Hunan is located at altitudes of 24–2042 m, and the corresponding maximum hemoglobin calibration level is 8 g/L40.

Vitamin D nutrition status evaluation criteria in children

The nutrition status of vitamin D was evaluated according to serum 25(OH)D concentration. The Chinese standard was adopted19: 25(OH)D concentration < 12 ng/ml, 12 ng/ml ≤ 25(OH)D concentration < 20 ng/ml, and 25(OH)D concentration ≥ 20 ng/ml were defined as vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency, respectively. Vitamin D inadequacy included vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted on SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data were statistically described as proportion or rate. The basic characteristics and prevalence of anemia were compared between groups using χ2 test. The nutrition status of vitamin D (deficiency, insufficiency, sufficiency) was compared using nonparametric rank sum test. The hemoglobin and 25(OH)D concentrations in children, which did not obey normal distribution, were expressed using P50 (P25–P75). The hemoglobin and 25(OH)D concentrations between groups were compared by non-parametric rank sum test. The adjusted and non-adjusted ORs and 95% CI in children with anemia, vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency (vitamin D sufficiency was the control for the dependent variable) were computed using binary and multinomial logistic regressions. To control potential confounders, multivariable logistic regression models were used to adjust for factors such as children’s characteristics, caregivers’ characteristics, and maternal gestational conditions. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the significant level was P < 0.05.

Results

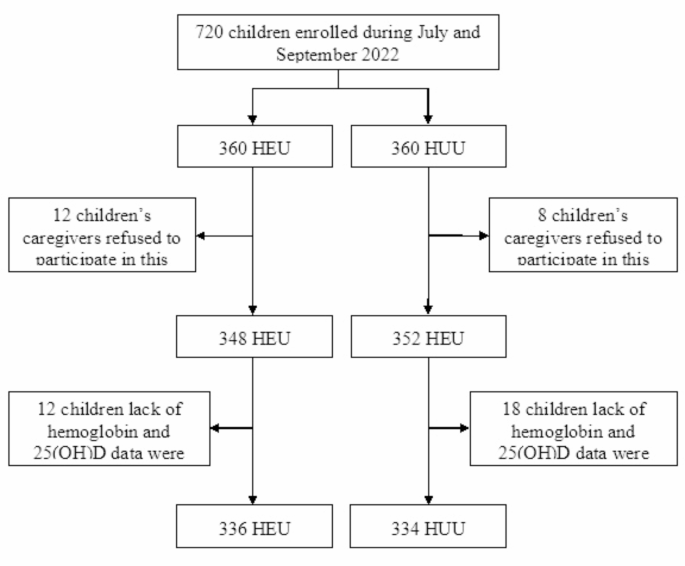

The recruitment of children is shown in Fig. 1. Initially, 720 children were enrolled during July and September 2022, including 360 HEU children and 360 HUU children. Of the HEU children, the response rate was 96.7% (348/360), and 12 children were excluded because their caregivers refused to participate in this study. Of the HUU children, the response rate was 97.8% (352/360), and 8 children were excluded duo to the same reason. Twelve HEU children and 18 HUU children were excluded from the study duo to lack of hemoglobin and 25(OH)D data. Finally, 670 children were included in the final analysis, including 336 HEU and 334 HUU children.

Flowchart of children recruitment.

Characteristics of participants

Comparison of characteristics between HEU and HUU children is summarized in Table 1. The two groups were significantly different in children’s ethnicity, birth gestational weeks, caregivers’ education level, occupation, and maternal pregnancy comorbidity, but not in children’s age, gender, birth weight, vitamin D supplementation, caregivers’ type, or maternal moderate/ severe anemia.

Anemia and vitamin D status

Table 2 shows the prevalence of anima and vitamin D inadequacy in the two groups. Table 3 shows the hemoglobin and 25(OH)D concentrations for the HEU and HUU children. The overall prevalence rates of anemia in the HEU and HUU children were 10.4% (all for mild) and 8.1% (7.5% for mild and 0.6% for moderate), respectively. The median hemoglobin concentrations were 120 (115–126) g/L in the HEU children and 122 (116–129) g/L in the HUU children. No significant difference between groups was found in prevalence or severity of anemia or hemoglobin concentrations. The prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in the HEU children (19.6% for deficiency and 25.0% for insufficiency) was significantly higher than that of HUU children (11.4% for deficiency and 16.2% for insufficiency). The median 25(OH)D concentration in the HEU children was 23.80 (13.50–34.08) ng/ml, which was significantly lower than that of the HUU children (32.08 (18.60–39.32) ng/ml).

HIV exposure for anemia and vitamin D status

After adjustment for the potential confounders, HIV exposure was significantly associated with an increased risk of vitamin D deficiency (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.72, 95% CI: 1.13–2.61) and vitamin D insufficiency (AOR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.01–2.34), but not with anemia (AOR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.32–2.01) (Table 4).

Discussion

The prevalence of anemia among the HUU children was 8.1%, which was similar to the rate among health children in Hunan in 2020 (8.8%)40, but was lower than that of the children under 5 years of age in Africa (60.2%) or Asia (India 53.4%, Thailand 24.9%, Indonesia 38.4%, Japan 16.7%) in 201920. The prevalence of anemia among the HEU children was 10.4%, which was obviously lower than that of HIV-infected children in Africa (38.8–61.1%)28,29,30or India (47.1%)41, and was slightly lower than that of HEU children under 2 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa (14.4%)32. The present study showed the prevalence of anemia among the HEU children was slightly larger than that among the HUU children, but not significantly. This finding is inconsistent with the results in Guangxi, China33, and is consistent with the results in Kenya30. A cross-sectional study in Guangxi showed the prevalence of anemia in HEU children aged 1–6 years was 18.2%, evidently higher than that in HUU children (5.1%), and maternal HIV infection was an independent risk factor for anemia in their children33. Another cross-sectional study in Kenya found that the prevalence of anemia among HEU children aged 18 to 36 months was higher than among HUU children (53.6% vs. 36.7%), but not differ statistically across groups30. In the present study, both HEU children and HUU children mainly suffered mild anemia, the HEU children had no moderate or severe anemia, and only 2 HUU children suffered from moderate anemia, which were different from the severity of anemia among HIV-infected children. Two studies in Ethiopia and one study in sub-Saharan Africa have shown that more than 40% of HIV-infected children have moderate or severe anemia27,28,29.

All HIV-infected mothers received antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy, and their children had access to be exposed to antiretroviral drugs at the embryo stage, and some antiretroviral therapy regimens included AZT. Moreover, these children received 4 weeks of AZT as a preventive therapy after birth. Previous studies have demonstrated that AZT evidently inhibited marrow and decreased hemoglobin levels in vivo42,43. In the present study, the prevalence of anemia among the HEU children was not higher than that of the HUU children, and the anemia was milder. The possible reason was that the HEU children aged above 6 months were not infected with HIV, the marrow inhibition effect of AZT had been eliminated, and the hemopoiesis function of marrow was recovered.

In addition, the prevalence of anemia among HEU children and HUU children in the present study were lower compared with children in Africa and South Asia, which may be related to the local socio-economic condition, medical services levels, and the implementation of children nutrition improvement projects. Hunan has implemented children nutrition improvement projects since 2012 and provided all children aged 6–24 months for free with 1 bag/day complementary food supplement (Yingyangbao for short) containing 6 vitamins (vitamin A, B1, B2, B12, D3, folate) and 3 minerals (iron, zinc, calcium) so as to improve children’s nutrition status and reduce the anemia prevalence44. In addition, in the PMTCT of HIV program, all HEU children were involved into special management, and were followed up by local child health care doctors from birth to 24 months of age, including HIV infection status monitoring, scientific feeding guidance, anthropometric measurements and nutritional status assessments. The child health care doctors gave parents scientific feeding guidance according to children’s growth and development conditions, so as to ensure children had healthy diet and adequate nutrition35.

Currently, the existing studies on vitamin D nutritional status mostly focus on HIV-infected children. Several cross-sectional studies show that vitamin D deficiency is ubiquitous among HIV-infected children, and the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is up to 40–75%45,46,47. Although some studies in Botswana and Tanzania focused on the vitamin D nutritional status among HEU children, they did not include HUU children as controls31,34,48. In our study, the prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy among HUU children was 27.6%, which was slightly lower than that of children aged 6 months in Guangzhou in Guangdong Province (35.1%)23 and obviously higher than that of children aged 1–3 years in Suzhou in Jiangsu Province (10.4%)49. The serum 25(OH)D concentration among HEU children was 23.80 ng/ml, which was evidently higher than that of HEU children aged 5–7 weeks in Tanzania (18.1 ng/ml)48. The prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy among HEU children was 44.6%, which was obviously higher than in HEU children aged 6 months in Tanzania (34.6%)34. The prevalence rates of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency among HEU children were 19.6% and 25.0%, respectively, which were obviously higher than in HUU children (11.4% and 16.2%, respectively). After the factors about children’s characteristics, caregivers’ characteristics, and maternal gestational conditions were adjusted, HIV exposure still increased the risk of vitamin D inadequacy among children. Specifically, the risk of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency among HEU children rose by 72% and 53%, respectively.

The increased risk of vitamin D deficiency among HEU children may be attributed to two reasons. First, the HIV virus and antiretroviral drugs (e.g., EFV, TDF) can interfere with the metabolism of vitamin D in the human body, leading to a decrease in 25(OH)D levels in HIV-infected mothers50,51,52. The maternal vitamin D insufficiency during pregnancy will directly affect the vitamin D concentrations of children. A positive correlation between maternal vitamin D levels during pregnancy and children vitamin D levels was reported53. Second, the risk of premature birth was increased among HIV-infected mothers, and their premature infants suffered from insufficient vitamin D reserves, resulting in a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in children born to HIV-infected mothers. The prevalence of premature birth in HEU children was 16.1%, which was obviously higher than that of HUU children (8.4%). Thus, it was recommended that HEU children be supplemented with 800 IU/D vitamin D (20 µg/d) after birth, and changed to 400 IU/D (10 µg/d) after three months until puberty. Meanwhile, appropriate outdoor activities were needed for HEU children to receive solar radiation for 1–2 h a day, and maximally expose their bodies to promote endogenous vitamin D formation.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has notable strengths, including the collection of hemoglobin and serum 25(OH)D from 336 HEU and 334 HUU children aged 6–24 months in five cities of Hunan Province, central and southern China, providing a substantial representativeness for the entire Hunan Province. Additionally, quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted on hemoglobin and 25(OH)D levels, respectively, providing valuable insights into the associations of HIV exposure with children’s anemia and vitamin D nutritional status. However, this study has some limitations. First, owing to the inherent characteristics of cross-sectional studies, the relationships of HIV exposure with anemia and vitamin D nutritional status identified in our study were statistical associations, rather than causality. Second, anemia diagnosis was based on hemoglobin level alone, but was not etiological diagnosis. Therefore, the etiological diagnosis of children’s anemia was unclear (e.g., iron deficiency anemia, nutritional megaloblastic anemia, thalassemia). Third, due to limitation in data collection, some potential confounders were not controlled, such as complementary food introduction, dietary patterns, and outdoor activity time, which led to certain confounding bias in our results. Fourth, although the sample size met the needs of this study, the age range of children was narrow and limited to 6–24 months old. Further large-scale cohort studies were needed to determine whether HIV exposure will have long-term effects on anemia and vitamin D nutritional status in children over 2 years old.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicated that HIV exposure in HEU children was associated with significantly increased risk of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency among children, but not anemia. The PMTCT program shall strengthen vitamin D supplementation in HEU children, and caregivers shall appropriately extend the HEU children’s outdoor activity time to reduce the occurrence of vitamin D inadequacy.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Duffy, C. et al. Multiple concurrent illnesses associated with anemia in HIV-infected and HIV-exposed uninfected children aged 6–59 months, hospitalized in Mozambique. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 605–612. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.19-0424 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

UNAIDS. HIV-exposed children who are uninfected. http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ (accessed 29 Aug 2024).

-

Zhong, S. et al. Prevalence trends and risk factors associated with HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis C virus among pregnant women in Southwest China, 2009–2018. AIDS Res. Ther. 19, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-022-00450-7 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Lou, H., Ge, X., Xu, B., Liu, W. & Zhou, Y. H. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: data analysis based on pregnant women population from 2012 to 2018, in Nantong City, China. Curr. HIV Res. 18, 458–465. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570162X18666200810134025 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Wu, S. et al. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C virus infections in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 29, 1000–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2023.03.002 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Gao, Y. et al. Analysis of loss to follow-up status and influencing factors of children born to pregnant women with HIV infection in China in 2019. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 45, 833–838. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20240105-00005 (2024). (in Chinese).

Google Scholar

-

Wang, A. H., Xiong, L. L., Xie, D. H. & Xie, Z. Q. Effect of mother-to-child HIV transmission prevention service in Hunan Province from 2011 to 2020. Chin. J. AIDS STD. 28, 1436–1439. https://doi.org/10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2022.12.20 (2022). (in Chinese).

Google Scholar

-

Wang, X. et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV—China, 2011–2020. China CDC Wkly. 3, 1018–1021. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2021.248 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Xia, W. et al. Neuropsychological development of human immunodeficiency virus-exposed uninfected infants/young children. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 24, 967–972. https://doi.org/10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2203037 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Wedderburn, C. J. et al. Early neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected children in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 6, 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00071-2 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Nyemba, D. C. et al. Growth patterns of infants with in- utero HIV and ARV exposure in Cape Town, South Africa and Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Public Health. 22, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12476-z (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bengtson, A. M. et al. In-utero HIV exposure and cardiometabolic health among children 5–8 years: findings from a prospective birth cohort in South Africa. AIDS 37, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003412 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Nyemba, D. C. et al. Lower birth weight-for-age and length-for-age z-scores in infants with in-utero HIV and ART exposure: a prospective study in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03836-z (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Mabaya, L., Matarira, H. T., Tanyanyiwa, D. M., Musarurwa, C. & Mukwembi, J. Growth trajectories of HIV exposed and HIV unexposed infants. A prospective study in Gweru, Zimbabwe. Glob. Pediatr. Health 8, 2333794X21990338. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X21990338 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Nyofane, M. et al. Early childhood growth parameters in South African children with exposure to maternal HIV infection and placental insufficiency. Viruses 14, 2745. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14122745 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Locks, L. M. et al. High burden of morbidity and mortality but not growth failure in infants exposed to but uninfected with human immunodeficiency virus in Tanzania. J. Pediatr. 180, 191–199e192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.040 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

World Health Organization. Anaemia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ANAEMIA (accessed 1 May 2023).

-

World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. https://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf (2011, accessed 29 Mar 2015).

-

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. WS/T677-2020 Method for Vitamin D Deficiency Screening (China Standard Press, 2020) (in Chinese).

-

World Health Organization. Prevalence of anaemia in children aged 6–59 months (%). https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/prevalence-of-anaemia-in-children-under-5-years-(-) (accessed 31 Mar 2021).

-

Oktaria, V. et al. Vitamin D deficiency in South-East Asian children: a systematic review. Arch. Dis. Child. 107, 980–987. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-323765 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

National Disease Control and Prevention Administration & National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Report on the Nutrition and Chronic Disease Status of Chinese Residents (2020) (People’s Medical Publishing House, 2021) (in Chinese).

-

Guo, Y. et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency among children in southern China: a cross-sectional survey. Medicine (Baltim). 97, e11030. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011030 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Ocansey, M. E. et al. The association of early linear growth and haemoglobin concentration with later cognitive, motor, and social-emotional development at preschool age in Ghana. Matern. Child. Nutr. 15, e12834. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12834 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Tavakolizadeh, R., Ardalani, M., Shariatpanahi, G., Mojtahedi, S. Y. & Sayarifard, A. Is there any relationship between vitamin D deficiency and gross motor development in 12-month-old children? Iran. J. Child. Neurol. 13, 55–60 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

De Marzio, M. et al. The metabolic role of vitamin D in children’s neurodevelopment: a network study. Sci. Rep. 14, 16929. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67835-8 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Tesfay, F. et al. Anemia among children living with HIV/AIDS on HAART in Mekelle Hospital, Tigray regional state of northern Ethiopia—a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 21, 480. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02960-1 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Fentaw Mulaw, G., Ahmed Yesuf, F. & Temesgen Abebe, H. Magnitude of anemia and associated factors among HIV-infected children receiving antiretroviral therapy in Pastoral community, Ethiopia: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Adv. Hematol. 2020, 9643901. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9643901 (2020).

-

Lubega, J. et al. Risk factors and prognostic significance of anemia in children with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 36, 2139–2146. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003374 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Oyungu, E. et al. Anemia and iron-deficiency anemia in children born to mothers with HIV in Western Kenya. Glob. Pediatr. Health 8, 2333794X21991035. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X21991035 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Tindall, A. M. et al. Vitamin D status, nutrition and growth in HIV-infected mothers and HIV-exposed infants and children in Botswana. PLoS One. 15, e0236510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236510 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Odhiambo, C. et al. Anemia and red blood cell abnormalities in HIV-infected and HIV-exposed breastfed infants: a secondary analysis of the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study. PLoS One 10, e0141599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141599 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Guo, X. F. et al. Anemia status and risk factors of HIV-negative children born to HIV-positive mothers in Guangxi from 1 to 6 years old. Guangxi Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 34, 854–856. https://doi.org/10.16190/j.cnki.45-1211/r.2017.06.015 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Rwebembera, A. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for vitamin D deficiency among Tanzanian HIV-exposed uninfected infants. J. Trop. Pediatr. 59, 426–429. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmt028 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Work specification for the prevention of HIV/AIDS, syphilis and hepatitis B mother-to-child transmission (. (2020). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fys/s3581/202011/fc7b46b2b48b45a69bd390ae3a62d065.shtml (accessed 12 Nov 2020) (in Chinese).

-

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Technical specifications for child feeding and nutrition guidance. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/cmsresources/mohfybjysqwss/cmsrsdocument/doc14756.doc (2012, accessed 20 Apr 2012) (in Chinese).

-

Zhan, S. Y. Epidemiology, 8th edition. (People’s Medical Publishing House, 2017) (in Chinese).

-

Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. módulo cobas e 601 para inmunoensayos. https://diagnostics.roche.com/es/es/products/instruments/cobas-e-601-ins-461.html (accessed 9 Aug 2023).

-

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. WS/T 441–2013 Method for Anemia Screen (China Standard Press, 2013) (in Chinese).

-

Li, H. et al. Anemia prevalence, severity and associated factors among children aged 6–71 months in rural Hunan Province, China: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 20, 989. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09129-y (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Shet, A. et al. Anemia, diet and therapeutic iron among children living with HIV: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 15, 164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0484-7 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Singh, A., Hemal, A., Agarwal, S., Dubey, N. K. & Buxi, G. A prospective study of haematological changes after switching from stavudine to zidovudine-based antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected children. Int. J. STD AIDS. 27, 1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462414522986 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Smith, C. et al. Serious adverse events are uncommon with combination neonatal antiretroviral prophylaxis: a retrospective case review. PLoS One. 10, e0127062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127062 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Huo, J. Ying Yang Bao: improving complementary feeding for Chinese infants in poor regions. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser. 87, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1159/000448962 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Meyzer, C. et al. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in HIV-infected children and young adults. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 32, 1240–1244. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e3182a735ed (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Mirza, A. et al. Vitamin D deficiency in HIV-infected children. South. Med. J. 109, 683–687. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000556 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Aurpibul, L. et al. Vitamin D status in perinatally HIV-infected Thai children receiving antiretroviral therapy. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 29, 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2015-0203 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Sudfeld, C. R. et al. Vitamin D status is associated with mortality, morbidity, and growth failure among a prospective cohort of HIV-infected and HIV-exposed Tanzanian infants. J. Nutr. 145, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.201566 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Zhang, Y., Ren, Z. L., Zhang, Y., Qiu, H. & Wang, W. Assessment of serum vitamin D levels in children aged 0–17 years old in a Chinese population: a comprehensive study. Sci. Rep. 14, 12562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62305-7 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Bergløv, A. et al. Prevalence and association with birth outcomes of low vitamin D levels among pregnant women living with HIV. AIDS 35, 1491–1496. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002899 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Wohl, D. A. et al. Change in vitamin D levels and risk of severe vitamin D deficiency over 48 weeks among HIV-1-infected, treatment-naive adults receiving rilpivirine or efavirenz in a phase III trial (ECHO). Antivir Ther. 19, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP2721 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Almeida-Afonso, R. et al. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation among persons living with HIV/AIDS in São Paulo city, Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 25, 101598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101598 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Özdemir, A. A. et al. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women and their infants. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 10, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.4706 (2018).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the five Municipal Maternal and Child Health Care Hospitals in Hunan Province (Changsha Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Hengyang Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Loudi Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Chenzhou Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, and Huaihua Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital).

Funding

This study was funded by the project of Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No.2020JJ5285).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. designed the study, wrote and revised the paper. M.L., S.T, L.W, Y.T. and M.Y. collected the data. H.L., J.Z. and J.G. conducted the statistical analysis and interpretation. S.Y., M.L. and S.T revised the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Provincial Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital (No.2019-S029). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained from all the caregivers of the included children.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Yuan, S., Liao, M. et al. Effects of HIV exposure on anemia and vitamin D nutritional status in children aged 6–24 months: a hospital-based cross-sectional study.

Sci Rep 15, 2839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87101-9

-

Received: 11 August 2023

-

Accepted: 16 January 2025

-

Published: 22 January 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87101-9

Keywords

- HIV

- Anemia

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Children

- China