Our findings showed that nutrition knowledge score was only significantly increased among girls (mean ± SD: 66.14% ± 14.13) at baseline to 68.43% ± 14.85 after 6 months in the intervention group while there was no significant different for the overall, gender, ethnicity and location without controlling the nutrition knowledge score at the baseline, ethnicity, gender and location. This finding which showed girls had significantly higher nutrition knowledge scores than boys, consistent with other studies [17, 18]. In the Malaysian context and culture, this could be due to girls being more concerned about nutrition and food selection. The findings of our study are also consistent with the findings of other studies which suggested that nutrition education programs were effective in improving adolescents’ nutrition knowledge [19,20,21,22]. However, after controlling for the nutrition knowledge score at baseline, ethnicity, location and gender as well as taking into consideration the cluster effects, the findings of our study showed that among these older schoolchildren, the NEI incorporated into the MyBFF@school intervention had no significant increase on the AMD of nutrition knowledge score in the overall, girls, urban, rural and Malays. In addition, there was no significant reduction of AMD of nutrition knowledge score for boys and non-Malays.

Similarly, after controlling for the nutrition attitude score at baseline, ethnicity, location and gender taking into account the cluster effects, there was no significant difference on the increase of AMD between the intervention and control group of nutrition attitude score in the overall, girls, location (urban vs rural) and Malays. There was also no significant reduction of AMD in the nutrition attitude score among boys and non-Malays although there was a significant reduction of AMD for nutrition attitude score among boys prior to controlling for the nutrition attitude score at baseline, gender, ethnicity and location. Although our NEI was undertaken for 24 weeks with relatively short contact hours, with a total of 12 contact hours of NEI, its positive effects on the nutrition attitude of the respondents may have been limited. This was noted in our findings, whereby we observed no significant increase in the AMD in the overall nutrition attitude of the children in the intervention group as compared to the control group. This might be attributed to the lack of extensive and continuous intervention, since intervention was conducted only once every two weeks for 45–60 min per session on alternate weeks for 24 weeks. Our findings are also consistent with those of a school-based nutrition education program among junior high school students in China, which suggested that no significant change of attitude in the students was due to the fact that continuous intervention was lacking [21].

Nevertheless, other studies have shown that even short durations of nutrition intervention, if conducted often (e.g., once a week for six weeks), can have positive effects on the attitude of schoolchildren [22]. Another study by Sharif Ishak et al. among adolescents aged 13 and 14 years old showed that although there were significant improvements in the nutrition knowledge of the intervention group, improvements in the attitude were not significantly difference between the intervention and control group [23]. These two studies however did not control the nutrition knowledge and attitude score at the baseline. In this respect, it seems that the more frequent the reinforcement, the more likely that it will bring positive results in nutrition attitude. Another study by Jha et al. among school children aged between 12 and 16 years old in India also showed no statistically significant difference in the mean score of attitude for healthy diet practices in both intervention and control groups [24]. The reduction of positive nutrition attitudes could, however, result from stigmatization, since the obesity intervention in our study only involved overweight and obesity adolescents and not children of normal weight. As reported by previous study, stigmatization of obese individuals can generate health disparities and interfere with obesity intervention efforts [25].

The by-item assessment of nutrition knowledge of the adolescents showed that, despite being in the category of older adolescents attending secondary schools, a high percentage of individuals experienced difficulty in calculating their BMI. There was only a slight increase in those able to correctly answer the BMI calculation in the intervention group (from 10.5% at baseline to 13.6% after 6 months). Therefore, more practical approaches toward understanding and applying the BMI concept should be given greater emphasis, since this forms the basis of self-monitoring of body weight.

The findings of our study also showed that the majority of older school children or adolescents knew that regular intake of vegetables can help in controlling body weight, that plain water should be consumed daily, and that the intake of carbonated drinks should be reduced because of their sugar content. The findings concerning the overall attitude toward eating vegetables ranged from 3.5 to 3.7 out of a maximum of 5 points on the Likert scale. Slightly higher values in the control group indicated that they did not like to consume vegetables. A similar study conducted on middle school students in Michigan showed that students involved in a nutrition education program were more likely to report increased fruit and vegetable consumption relative to students in a control group [26]. Findings from Malaysia National and Health Morbidity Survey 2017 showed that only 9.1% of overweight adolescents and 6.0% of obese adolescents consumed an adequate amount of vegetables [5]. A similar trend was observed for those who dislike plain water, which noted a higher scale score of 4.12 to 4.20 on a 5 point Likert scale. Although the majority of the children knew the effects of consuming carbonated drink, they did not deny that they liked carbonated drinks. Various studies have shown that excessive intake of sugar from soft drinks increases energy intake, thus increasing the risk of becoming overweight or obese [27, 28]. The WHO guideline for sugar intake recommends the reduction of free sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake in both adults and children [29]. Therefore, concerted efforts have been made to reduce the intake of carbonated drinks, especially among adolescents, whereby the current Malaysian School Management Canteen Guidelines has banned the sale of carbonated drinks in school canteens.

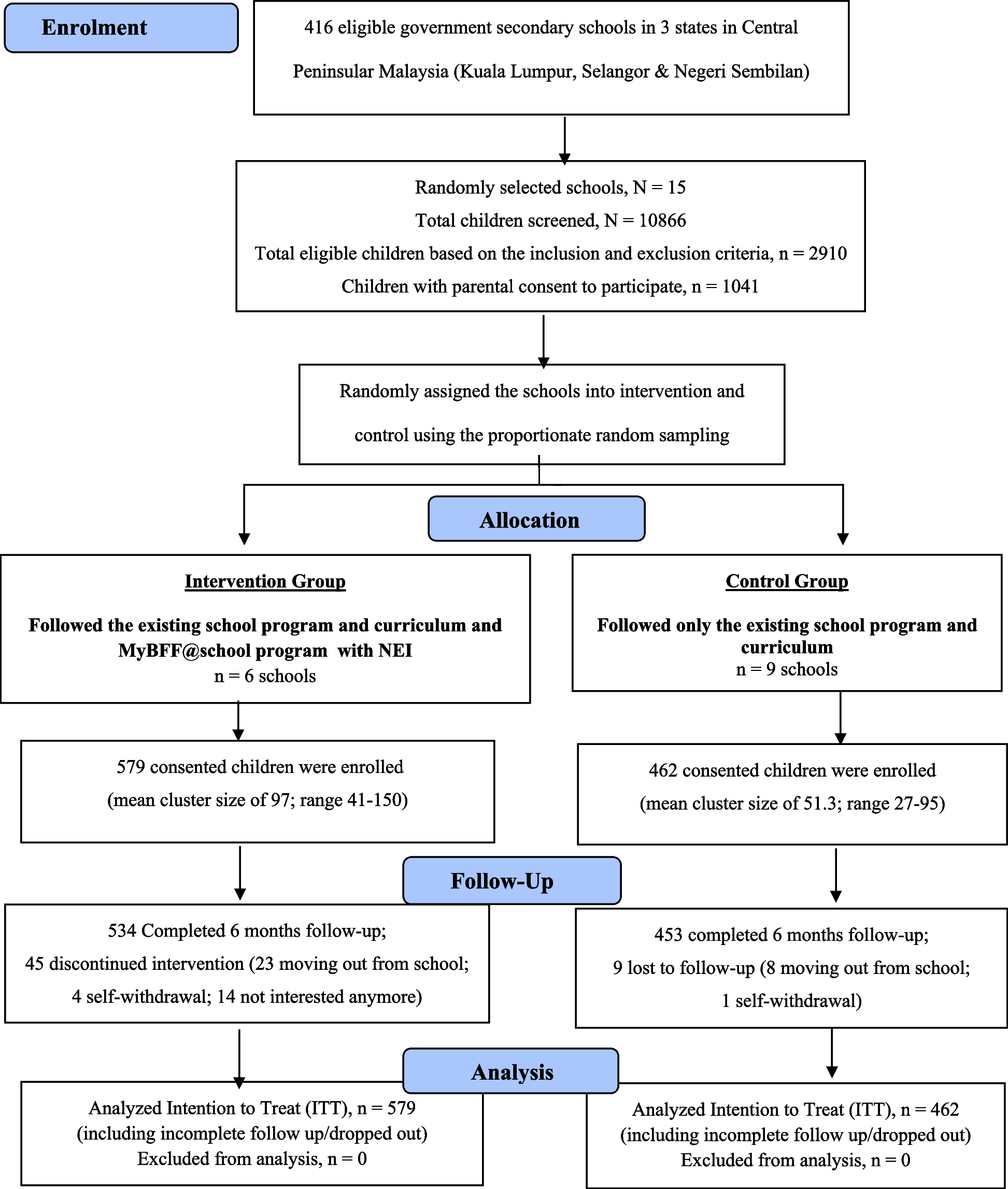

One of the strengths of our study was this was designed as a Randomised Cluster Control Trial taking into consideration the cluster effects, location (urban vs rural) as well as the ethnicity. Therefore, the findings that could be generalized and adopted to the population. On the other hand, one of the limitations of the present study was the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for nutrition knowledge and attitude were rather low which could possibly affect the overall consistency of the nutrition knowledge and attitude. Another limitation of the study was the MyBFF@school was lacking of direct parental involvement despite these schoolchildren had obtained the parental consent to participate in the study. Besides that, since the nutrition education intervention was conducted after school hours, full participation of these children was rather a challenge.