Welcome to Earth.Org’s in-depth exploration of the endangered Lankanectes pera, a species of corrugated frogs from Sri Lanka Frogs teetering on the brink of extinction. In this article, we delve into the fascinating world of these remarkable creatures, shedding light on their unique characteristics, ecological importance, and the urgent conservation efforts being undertaken to protect them.

—

Family: Nyctibatrachida

Genus: Lankanectes

Species: Lankanectes pera

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Population: Unknown

Between 2012 and 2016, researchers conducting field surveys for Lankanectes in the cloud forests of the Knuckles Mountain Range, Sri Lanka, made a surprising discovery: a new species of frog endemic to the region. Although Lankanectes was previously believed to be a monotypic genus represented by Lankanectes corrugatus, a species of frog found in submontane habitats across southern, western and central Sri Lanka, researchers determined that the newly discovered frog belonged to a morphologically and genetically distinct species. The undescribed frog was named Lankanectes pera in honour of the University of Peradeniya, affectionately referred to as “Pera” by its alumni. The two Lankanectes species were further given the common name of Corrugated Frogs, referring to the numerous and prominent traverse skin folds found on the bodies of both. Although only recently discovered, Lankanectes pera has been evaluated as a Critically Endangered species due to its small population size and limited predicted distribution, as it is believed to be a montane isolate adapted to high-altitude bioclimatic conditions that are currently threatened by climate change and anthropogenic activity.

Discovery & Evolution

Although numerous endemic anuran lineages exist in mainland India, such as Nasikabatrachus, Micrixalus and Nyctixalus, the only Sri Lankan amphibian lineage that survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event (66 million years ago) is Lankanectes. Molecular studies of the genus have confirmed its distinctiveness and ancientness among South Asian anuran lineages, and its closest extant relatives are representatives of the Nyctibatrachidae family. Prior to 2018, Lankanectes was believed to be a monotypic genus represented by a single, widely-distributed species, Lankanectes corrugatus.

While conducting field work in the Knuckles Mountain region, specifically on streams found within cloud forests (unique tropical mountainous regions where rainfall is heavy and condensation is persistent, causing a layer of clouds at canopy level), researchers discovered a small population of frogs that appeared to be morphologically different from Lankanectes corrugatus. Noting that a substantial number of Nyctibatrachus species are montane endemics, researchers recognised that the existence of an undescribed species of Lankanectes within Sri Lanka was possible.

By examining the external morphology, genetics and climatic niche of the unfamiliar frog population, researchers ultimately determined that they had discovered a new species of frog, Lankanectes pera, and described their findings in a paper published in 2018 in the journal Zootaxa. With reference to genetic testing, researchers found that the genetic distance observed between the two species of Lankanectes (3.5−3.7% uncorrected genetic distances for 16S rRNA) was consistent with the range of species-level genetic distances commonly founding amphibian sister taxa.

The two species differed in 16 mutational steps (whereas only one to four mutational steps are seen within populations of Lankanectes corrugatus), indicating that they descended from a common ancestor and went their separate evolutionary ways.

Morphologically, the two species can be distinguished on several subtle but consistent differences. Nevertheless, the primary distinguishing feature between the two species is their habitat range. Lankanectes pera has a much smaller predicted distribution than Lankanectes corrugatus, as the former has only been located in pristine, isolated montane habitat with clear-water streams, sand, rock and canopy cover. In contrast, Lankanectes corrugatus typically occurs in habitats with muddy substrate, such as marshes and rice paddies, where they burrow in mud and plant litter. Researchers believe that the niche endemic habitat of Lankanectes pera, and the specialisations that the species has developed to thrive in such an environment, have prevented it from spreading.

Appearance & Morphology

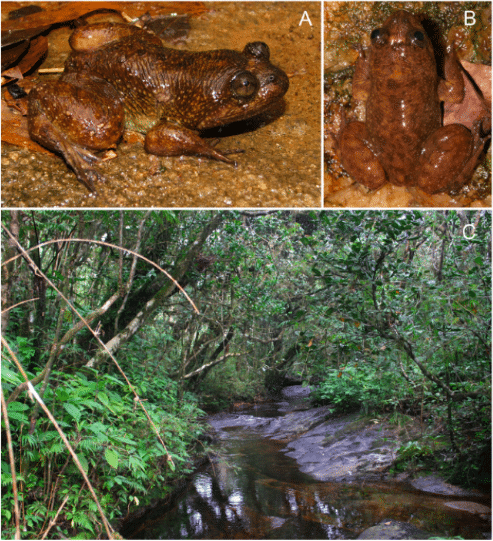

In their paper, researchers described Lankanectes pera as having a stout body, a dorsally flat and wide head, a large tongue, short but strong forearms, and strong legs. Their fingers and toes are thin, with large, rounded tips, and only their toes are webbed. They do not possess a tympanum, which is a membrane that typically separates a frog’s outer and inner ear allowing the animal to hear in the air and below water. They have tusk-like vomerine teeth, which are present in most species of frogs and are utilised to capture and hold prey. The skin on the head of Lankanectes pera is not co-ossified (in some species of frog, the connective tissue of the dermis ossifies with underlying dermal bones, which may reduce evaporative water loss), while corrugations (prominent dermal folds) and glandular warts are present on dorsal surface of the species’ head, body, forelimbs and thighs. The dorsal side of Lankanectes pera is chocolate brown with irregular dark brown patches, while its chest, belly and ventral sides are white or light brown.

Habitat and Ecology

The predicted geographic distribution of Lankanectes pera is extremely limited, estimated to be approximately 360km2. According to the IUCN, the extent of occurrence of the species is around 89km2 and it is believed to have a small population size that occurs in a single, threat-defined location. In fact, Lankanectes pera has been described as a micro-endemic species. In contrast, Lankanectes corragatus has a predicted distribution of 14,120km2 and a large population size.

So far, Lankanectes pera has only been observed inhabiting pristine streams that flow through closed-canopy montane forests on the highest peaks of the Knuckles Mountain range (located in the Dothalugala, Bambarella and Riverstone regions of Sri Lanka), at altitudes of 1,250 to 1,600 metres above sea level. These streams are typically characterised by clear, shallow, slow-flowing water with sand and rock substrates. Males are typically found under rock crevices in flowing water, vocalising in chorus at night, but are occasionally heard calling during the day. Lankanectes pera tadpoles are large and inhabit deeper regions of streams where decaying vegetation tends to gather, indicating resource partitioning between adults and tadpoles. The species does not tolerate habitat disturbance.

Ecological niche models have suggested that Lankanectes pera is a montane isolate, adapted to high-altitude bioclimatic conditions. Although it is predicted that suitable climatic conditions are also present in the northern region of the central mountains, this area is climatically and ecologically remote from the current range of the species.

Ecological Importance

Although the ecological background of Lankanectes pera has not been studied comprehensively, frogs play a critical role in their respective ecosystems as part of the food chain. Amphibians also play an important part in environmental conservation as an indicator species. When environmental degradation, climatic shifts and pollution affect a habitat, frogs are often among the first casualties and thus provide an early warning signal for ecosystems under threat.

Threats

Since its discovery, Lankanectes pera has been listed as Critically Endangered under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The species has an extremely small population size and area of occupancy, which is increasingly threatened by climate change and anthropogenic activity. Having adapted to an exceptionally specific, pristine habitat, and intolerant to any form of degradation or disturbance, the continued decline in extent and quality of the Knuckles Mountain Range will ultimately result in the extinction of Lankanectes pera before this remarkable species is properly studied and understood. Cloud forests are an ecologically unique habitat, formed by a delicate combination of climatic and topographical conditions.

These high-altitude, tropical montane environments are characterised by high rainfall and humidity levels, and where, through a process of “lateral cloud filtration”, a layer of clouds or mist persist at canopy level. Air currents that travel inland and encounter high montane slopes gradually cool and form clouds as they rise, resulting in a shroud of fog at high altitudes. These clouds then filter through forest vegetation, condensing on leaves and saturating moss, thereby supporting an incredibly wide range of flora and fauna. The specificity of the conditions in cloud forests, including limited sunlight, cool temperatures, high altitudes, nutrient-depleted soil, high humidity, and the prevalence of dense vegetation, result in high levels of species endemism. Unfortunately, this specificity also renders cloud forests highly vulnerable to global warming and shifts in climate patterns.

In 2022, it was estimated that a mere 1% of global woodlands were categorised as cloud forests, compared with approximately 11% in the 1970s. Annual rainfall has been sharply declining across the Knuckles Mountain region, which has consequently become significantly drier and more seasonal.

From an annual average rainfall of approximately 2,500mm one century ago, the highlands of Sri Lanka now receive between 1,500 and 1,900mm of rain per year. In addition to significant changes in the spatial and temporal distribution of rainfall, global warming has had severe impacts on high-altitude montane environments and their ecosystems. An average annual temperature increase of 0.8C has been recorded across Sri Lanka over the past century, while average temperatures in the highlands have risen annually by approximately 1.1C. In addition to increasing the risk of forest fires, this prevalence of unusually warm temperatures and dry climatic conditions inevitably results in the reduction of moisture and condensation within cloud forests, disrupting the delicate climatic conditions necessary to sustain this unique habitat and the array of endemic and micro-endemic species that rely on it.

Species of flora and fauna that are adapted to inhabiting cooler regions are forced to move to higher altitudes in search of appropriate climatic conditions. This effectively reduces the distribution of sensitive species, isolating them to extremely high-altitude, potentially unsuitable environments. The complete loss of cloud forests, should adverse climate patterns persist, would inevitably result in the mass loss of biodiversity across ecosystems where highly specialised species can no longer find habitats with these unique conditions.

The Knuckles Mountain Forest Reserve (KNFR) is further threatened by the continuous expansion of agricultural practices, particularly illegal cardamom plantations, and the consequential pollution that accompanies deforestation and pesticide use. A significant portion of primary forest within the KMFR has being cleared to supply fuelwood and timber for surrounding villages, for the cultivation of cash-crops, such as tea, and for the processing of cardamom. Further anthropogenic threats include unregulated research work, the construction of resorts and infrastructure, uncontrolled tourism access, and deliberate forest fires.

Another potential threat to Lankanectes pera is forest dieback, which was first observed within Sri Lanka’s cloud forests in 1978. Although numerous studies have been conducted on the aetiology of forest dieback, it remains a poorly understood phenomenon, although some have expressed concern that a particular environmental stressor that kills extensive strands of woody vegetation may negatively impact amphibians. Research has shown that the acidity from mist and rainwater may threaten highland biota in Sri Lanka, however there is no direct evidence that amphibians are affected; it is believed to have deleterious effects on species that inhabit areas where mist persists for a long time, and that species that can be found in open habitats with aquatic life history stages in shallow, lentic habitats could be more susceptible to this threat. Nevertheless, further research is clearly needed on the subject.

You might also like: 41% of Amphibians Are Threatened with Extinction As Experts Blame Climate Change and Habitat Loss

Conservation

The discovery of Lankanectes pera and their perilous state within the cloud forests of Sri Lanka brought to light the urgent need for conservation measures for unique, climatically-delicate regions that harbour highly specialised species of flora and fauna. Apart from Lankanectes pera, the Knuckles Mountain Range is already known as a critical refuge for at least eight micro-endemic species that are categorised as Endangered or Critically Endangered. Since the habitat requirements of Lankanectes pera are different from those of other threatened micro-endemics, and bearing in mind current predicted global climatic warming models, the implementation of progressive, evidence-based conservation measures are desperately needed to prevent mass loss of biodiversity in the region.

In 2000, the Knuckles Mountain Range was declared as a conservation forest, effectively banning cardamom cultivation in the region for the protection of the incredible biodiversity found within the range. In 2010, the Knuckles Conservation Forest was further included in the UNESCO World Natural Heritage list. Nevertheless, the consequential socio-economic impacts of the ban on cardamom plantations caused significant hardship for local farmers, who had lost their primary source of livelihood. Subsequent studies on the effects of cardamom cultivation demonstrated that the practice altered forest structure, canopy openness, species composition, soil properties, watershed properties, natural regeneration and evolution processes of the Knuckles Mountain Range, resulting in various deleterious environmental effects.

Negative modifications of ecosystem services, such as the reduction of water quality, depletion of genetic resources, and soil erosion, rendered cardamom cultivation an unsustainable source of income for surrounding communities. Therefore, the ban was upheld and a holistic approach was suggested for creating alternative sustainable sources of income for villagers in the region, including engagement in the tourism industry to support and reap the benefits of the World Natural Heritage status of the range. While these initiatives are a positive step towards the sustainable protection of forest habitats, continued and strengthened management of protected areas, particularly where Lankanectes pera occurs, and additional protection of potentially suitable streams and forests elsewhere in the mountain range are crucial.

Nature-based solutions focusing on ecosystem services have also been widely discussed in relation to cloud forests. In approximately 25 countries where cloud forests are found, hydropower dams are used to produce electricity and over half of these rely on water from cloud forests.

You might also like: What Are Nature-Based Solutions And How Can They Help Tackle the Climate Crisis?

It has been suggested that implementing a tax on existing dams could cultivate a revenue stream for the protection of these sources of water, which would make the protection of forests a more prosperous choice when compared to clearing forests for agriculture and timber. This prospect is of particular interest in countries where environmental conservation measures are inadequate or often bypassed for economic reasons. While it is still unclear whether profit-motivated initiatives are a sustainable, ethical option of the protection of natural ecosystems, cloud forests are fundamentally important for the survival of an incredibly wide variety of flora and fauna, as well as for indigenous communities, and desperately require more attention from conservationists.

Lastly, and most importantly, Lankanectes pera requires a specific species conservation plan, supported by further research and monitoring initiatives. Given the multitude of threats that this species faces, and the limited knowledge on the behavioural patterns, breeding seasons, mating practices, ability to produce offspring, development, and ecology of Lankanectes pera, designing an effective conservation plan is difficult at present. Nevertheless, Peradeniya University is well equipped to lead the implementation of conservation measures, with some of the best academics in the fields of science and humanities within such close proximity of the habitat of Lankanectes pera. Although the present known habitat of Lankanectes pera is surrounded by Lankanectes corrugatus, effectively creating a genetic barrier for the spread of Lankanectes pera to further mountain ranges, authors of the 2018 study noted that relict populations that are genetically similar to Lankanectes pera could inhabit adjacent Central Highlands, indicating that there is still much to learn about the genus Lankanectes.

Featured image: Senevirathne et al (2018)

If you enjoyed this article about the endangered Lankanectes Pera, you might also like: Red Pandas: Endangered Animals Spotlight