On Sept. 30, 300 community members along with UB students, faculty and staff gathered for the sixth annual “Igniting Hope” conference. The gathering has matured into what organizers describe as a movement aimed at bringing lasting change to the region by ending race-based disparities and their devastating impacts on the health of Black people, Hispanic people and other underrepresented groups.

The movement and the conference clearly benefit from the “UB-supported institute, which indicates the university’s strong support of our work with the community, providing critical longevity to the movement,” said organizer Timothy F. Murphy, SUNY Distinguished Professor and director of UB’s Community Health Equity Research Institute and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

President Satish K. Tripathi made welcoming remarks in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, noting that health inequity is a problem that will take the entire university community to address, “regardless of specialty.”

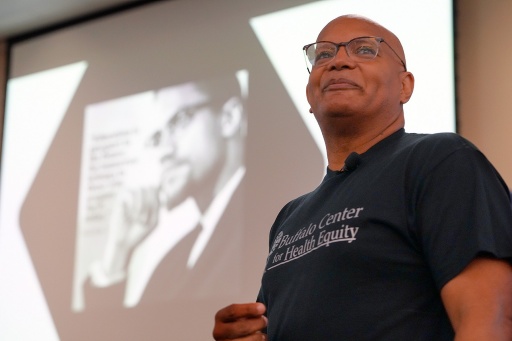

But doing so will require the clear demonstration that change is possible, said Rev. George Nicholas, pastor of the Lincoln Memorial United Methodist Church, CEO of the Buffalo Center for Health Equity and a conference organizer.

Quoting Malcolm X, who famously said “Education is the passport to the future,” Nicholas noted that three-quarters of third-graders in the Buffalo Public Schools are not reading at grade level.

“If they’re already behind in third grade, how can they ever dream of getting ahead?” he asked. Nicholas said it is critical that demonstration projects start be implemented.

“What if we do a demonstration project on the East Side where we find a neighborhood or two and commit to bringing every child up to grade level, bringing every home up to code, and improving primary care access,” he said. Success in one neighborhood will demonstrate that it is possible to do it in others.

A community’s access to primary care, for one thing, improves outcomes and lowers costs. “We know this stuff!” he declared. “We know the barriers.”

One often underappreciated barrier is difficulty in accessing dental care, according to Marcelo Araujo, dean of the School of Dental Medicine. He introduced the first keynote speaker, Natalia Chalmers, chief dental officer of the Office of the Administrator, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Chalmers informed the audience that when people without dental insurance have dental pain or issues, they go to the emergency room, where a visit can cost anywhere from hundreds to thousands of dollars. “And they don’t even get an extraction,” she said. “Instead, they get an opioid prescription and they’re told they should go to a dentist. So don’t go to the ER for a toothache — you won’t get better.”

When the system fails, she said, tragedies can happen. In 2007, a 12-year-old Black boy living in Maryland developed a tooth abscess. Without adequate insurance, he lacked regular dental care. It developed into a severe brain infection that killed him. That tragedy spurred outrage, she said, and almost overnight the state boosted Medicaid reimbursement for dental care.

Chalmers said that remote area medical clinics are often the only way that underinsured families get access to any dental care; these RAMs, as they are known, are temporary medical and dental clinics where volunteer providers provide care to hundreds of patients, typically during a weekend.

“They are a great point of access,” she said, “but do you really want to wake up at 4 a.m. so you can get a number and wait in line for hours for dental care? Is this equitable access to care?” Chalmers looks forward to a day when there is no need for RAMs to exist.

The afternoon keynote topic delved into issues at the core of medical research, such as informed consent and medical mistrust. Moderated by Jamal Williams, assistant professor of psychiatry in the Jacobs School, the session featured David Lacks and Veronica Robinson, the grandson and great granddaughter, respectively, of Henrietta Lacks.

Lacks was the young, African American mother whose cancerous cell tissue has become, since her untimely death in 1951, one of the most important medical research tools ever discovered. Without her knowledge or consent, tissue was removed during a biopsy she underwent at John Hopkins Medicine and shared with the hospital’s tissue lab.

Unlike all other cells, hers (now named HeLa cells after her) didn’t die in the lab. Instead, they rapidly divided over and over, a phenomenon that to this day remains a unique medical mystery. HeLa cells have played a major role in the development of major medical advances, from new cancer treatments to the invention of vaccines that protect against polio and COVID-19 to in vitro fertilization.

Today, Lacks family members are active in the National Institutes of Health’s HeLa Genome Committee, but for decades they had no idea of the extraordinary role Henrietta played in modern medicine. Neither she nor her family was ever given the opportunity to provide informed consent. Only after a tenacious science writer named Rebecca Skloot started researching the story, which eventually became “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” did the family learn about their ancestor’s incredible legacy.

“Had they asked her, she would have probably given consent,” said Veronica. “We have been unwilling participants, which keeps us from being a part of science,” she said of her family and the African American community as a whole. “It starts with saying we can’t be silenced anymore.”

“The Henrietta Lacks story is a story of science at its best and at its worst,” said Williams.

“We are now at another critical juncture,” he said, “which is the intersection of having to reckon with past exploitation in biomedical research and the need for historically marginalized groups to be included in studies that pertain to their long-term health.”

Understandably, the Lacks family was skeptical when Skloot began her research.

“When we were introduced to her, I thought, ‘is this just another white woman who wants something from us?’” said Veronica. “That was a big fear of the family, but Rebecca was very persistent. It has opened up a lot of conversations.”

David noted, “She took but she also gave back. The biggest thing to come out of this is communication. Even if you don’t monetize it, let people know what’s going on!”

Veronica agreed, noting, “One of the worst things you can take from a person is their right to know; then you can’t make informed decisions. If it comes from me, then it’s not medical waste, it’s mine. There’s a difference between something that’s given and something that’s taken. We have to change that narrative.”

In addition to the keynote speeches, breakout sessions took place on topics including Black Lungs Matter, food and elders, neighborhood restoration and medical mistrust.

More information about Henrietta Lacks, the Igniting Hope conference and the issues discussed at it is available in the Sept. 26 WBFO conversation with Pastor George Nicholas.