REPORTS OF GRASSROOTS outrage have been greatly exaggerated. Bankrolled anger is a big business, often weaponized for money, power, or both, and “cancel culture,” as it is often described, has become an increasingly complicated political football in the digital age. However, there is one area where outrage culture has always been a potent force—popular culture. Kliph Nesteroff’s new book, Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars, details the evolution concept within, and levied against, film, television, radio, music, and comedy. Nesteroff shows us the importance of sharing the history of fear and intimidation surrounding popular culture so that we can be more informed when we see it today, as the issues facing the moral crusaders of yesteryear are not unlike what we find in 2023.

In the class that I teach on censorship, I regularly welcome our campus librarian to discuss book banning. Her relationship with popular culture outrage became terrifying when she was a small-town librarian and the pushback against certain books led to death threats targeting members of her occupation. Understandably, several resignations followed. Stories like hers show the real life, local impact of defending literacy (not to mention those pesky First Amendment rights) in some communities.

Last semester, she brought a stack of regularly banned children’s books from the local library for our students to analyze. In Mary Hoffman and Ros Asquith’s The Great Big Book of Families (2010), for example, one of my students found the line “Some children have two mummies or two daddies” carefully taped over. These college-age digital natives, who rarely bat an eye at viral outrage, were appalled and surprised to see this poorly implemented real-world example. These local instances are products of national debates and controversies. In 2009, religious fanatics near University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s West Bend campus wanted Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower (1999) removed and replaced by books written by “ex-gays.” This same community just got rid of Orson Scott Card’s 1985 novel Ender’s Game for eighth graders. Even more confusing is the case of the Texas teacher who was recently fired for instructing her students to read from an illustrated adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary.

¤

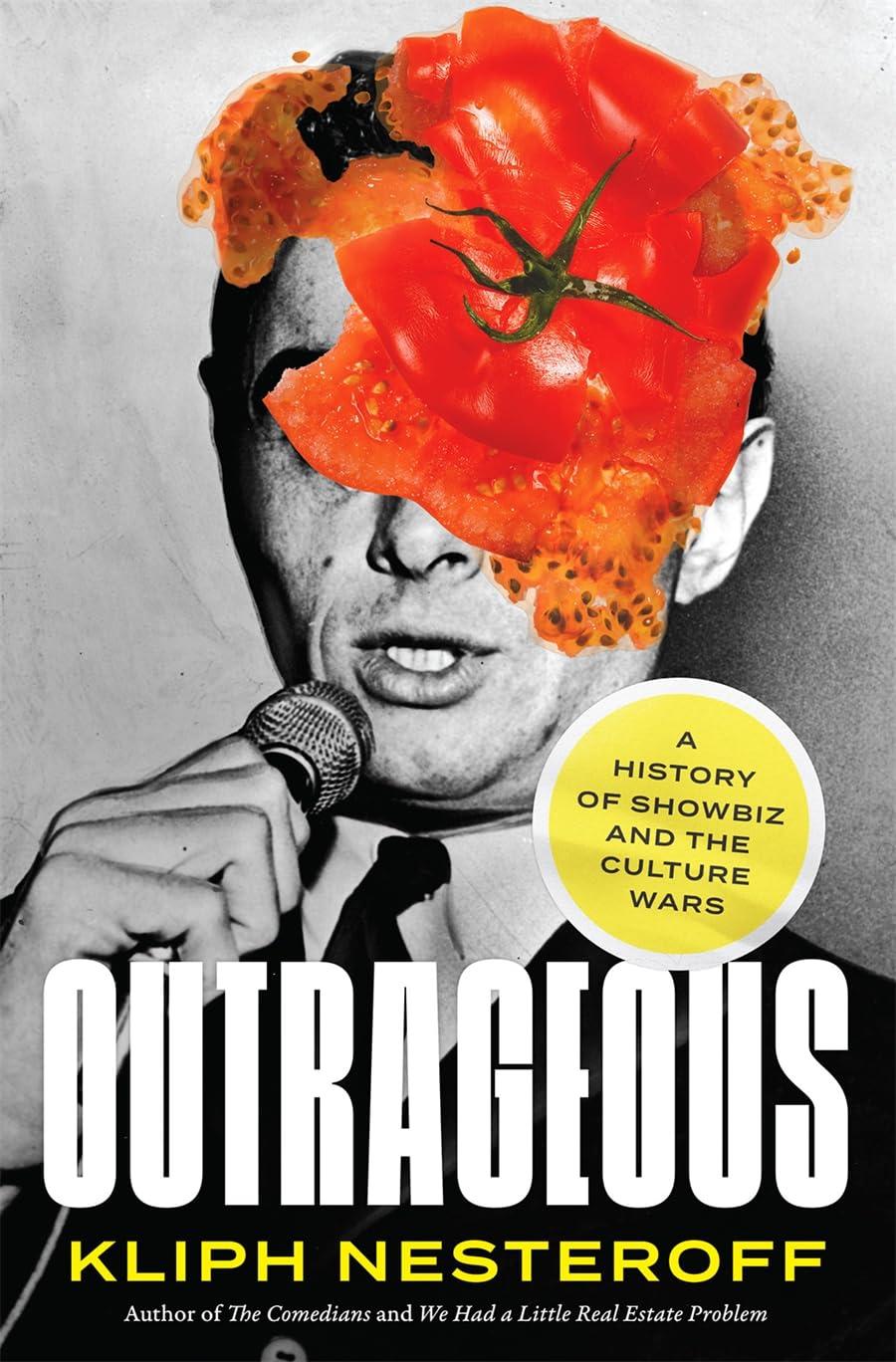

Every time we come across viral anger about popular culture, it can feel like “[w]e are engaged in a battle for the soul of the nation,” writes Nesteroff, a pop culture historian, in his new book. Having cut his teeth as a stand-up comic, Nesteroff is best known as a welcome talking head in numerous documentaries about the history of comedy, as well as the author of The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels, and the History of American Comedy (2015) and We Had a Little Real Estate Problem: The Unheralded Story of Native Americans and Comedy (2021). Purposefully avoiding comment on today’s debates, Nesteroff’s goal is to show us that the old refrain that “you can’t joke about anything anymore” is just that—an outdated chorus. “The purpose of this book is to provide context for showbiz controversies as they arise—and how to make sense of them,” he writes.

Comedy (and the larger scope of popular culture) has always pushed boundaries and, therefore, has been designed to offend. Though Nesteroff is careful to avoid any showbiz controversy in the 21st century, he recognizes that so many national conversations are “intentionally composed to incite and manipulate the reader.” While this may feel like a new phenomenon to some, sadly it is not. Nesteroff quotes historian Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 The Paranoid Style in American Politics to establish continuities with the present: “The paranoid spokesperson sees the fate of this conspiracy [to upend a specific way of life] in apocalyptic terms […] [H]e constantly lives at a turning point: it is now or never in organizing resistance.” This paranoid style of outrage and fearmongering has been at work in our society for well over a century.

Outrageous starts by showing us that “American show business essentially begins in the 1830s with the blackface minstrel show.” “Ever since that time,” writes Nesteroff, “audiences have complained.” Though Outrageous makes very minimal connections to today, these minstrel controversies persist, most commonly relating to “digital blackface” and white people’s use of GIFs featuring African Americans. However, as Nesteroff chronicles, not all outrage has aged as well. Many people disapprove of blackface today—though perhaps not as many as you’d think. There was also a time when the Twist sent shock waves through the nation’s prudes, but today the dance raises very few eyebrows. Same goes for the Beatles—what was once the Devil’s music is now classic rock playing at your local department store.

Attacks on mass popular culture first peaked with outrage over the nascent art of cinema. Fearing federal censorship, the film industry decided to self-censor. Outrageous includes some history of film controversy, featuring the technologically influential but socially reprehensible Birth of a Nation (1915). Its director, D. W. Griffith, was raised in the postbellum South, his childhood draped in the Lost Cause legends that plagued the region and circulated throughout the country via films like his. (Importantly, Birth of a Nation, controversial then as now, brought a fledgling NAACP to national attention.)

Nesteroff also highlights the Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle scandal, as it lit a fire for anti–pop culture crusaders looking to paint Hollywood as a sanctuary of vice and debauchery. When sound movies came in, Mae West had an all-too-brief peak of fame for her sexually suggestive comic roles; when censorship strictures were tightened in 1934, West’s career took a major hit. Even with the decline of the Motion Picture Production Code and the rise of the ratings system in the United States, fear and intimidation over movies have persisted.

During the rise of television, the continued backlash against Amos ’n’ Andy produced enough pressure to end the medium’s use of blackface altogether. Predictably, comments flew regarding the death of comedy. “Taboos have killed off most sources of American humor,” complained one newspaper column at the time. Nesteroff shows how, as public taste changed, previous generations of comics—including West and the legendary Lucille Ball—scoffed at television’s increasing inclusion of profanity. Organizations of moral crusaders came out of the woodwork. Conservative activist group Morality in Media—which, as Nesteroff shows, was funded by the Coors fortune—fought to get Playboy magazine banned from stores and went after screenings of The Godfather (1972) and anything else that was going to push the United States into “barbarism.” The irony of a beer company funding the morality police may have been lost on this group.

One of the book’s greatest strengths is how it outlines the origins of outrage, tracking its evolution (and stasis) historically. What was once anger expressed by religious groups became lavishly funded outrage machines stemming from the Cold War–era John Birch Society, an organization which continues to impact the nation. Among the founders was candy and conspiracy solicitor Robert W. Welch Jr. One of the Society’s bookstores was operated by Charles Koch (whose last name should ring a few bells). The Society propagated anti-integration views, held book burnings, and kept pressure on Hollywood and the media for liberalizing the country. Some members of Hollywood were recruited by the Society, such as screenwriter Morrie Ryskind, who authored some marvelous comedies of the 1930s, including Animal Crackers (1930) and My Man Godfrey (1936). Ryskind’s son Allan, it is worth noting, published Hollywood Traitors: Blacklisted Screenwriters; Agents of Stalin, Allies of Hitler in 2015, a book carrying evaporated water and decrying Hollywood’s communist-infiltrated Golden Age. The John Birch Society was lampooned by comedians in every medium. Original Tonight Show host Steve Allen received death threats for his jokes about the Birchers.

Later profiled is Paul Weyrich, co-founder of the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank funded by a multimillion-dollar donation by Joseph Coors. The name of the foundation may sound scholarly, but all it did on its founding in 1973 was provide a new veneer for Bircher beliefs. The organization sparked a growth of other similar groups, all Christian-affiliated, working toward the dismantling of popular culture. By the 1980s, such groups attracted televangelists like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, and stoked public fears around music and entertainment, resulting in the burning of hip-hop and heavy metal records.

Enter the Parents Music Resource Center, or PMRC, the heart and soul of moral crusading against music in the 1980s. Spearheaded by Tipper Gore and a string of other government-affiliated spouses, the PMRC sought to silence musicians whose music they didn’t like. The PMRC, like previous “outrage” organizations, was endorsed by radical religious groups like Focus on the Family, which “endorsed conversion therapy, and rejected the theory of evolution.” Such outrage led to the Moral Majority, a collective of Christian conservative groups that regularly stuck their neck into the culture wars. Though not mentioned in the book, the only thing to come out of the PMRC is the often-ignored “Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics” label still found on some albums. Some stores, including Wal-Mart, refused to stock albums featuring the advisory.

Just about all fearmongering over popular culture is justified as a means of “protecting the children.” Nesteroff argues that this is “a constant reminder that concern for children was [and is] a cover for bigotry.” History shows how kids are used as an excuse to attack any popular culture phenomenon that has aided social and racial integration. The John Birch Society insisted they were just looking out for the kids—a very specific subset of kids, it was clear—as they fought desegregation in schools.

And today, the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), with which Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett and Senator Josh Hawley are connected, works to fight abortion, ban contraceptives, and criminalize homosexuality—all to provide a hypocritical interpretation of family values about saving the children. In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis has cultivated an atmosphere of fear and judgment leading to nearly 1,500 book bans in the last year. Like nearly everything covered in Outrageous, book banning across the country is tied to groups like Moms for Liberty, yet another deceptively titled organization that hides behind an ostensible love of those most in need of protection.

Nesteroff covers an impressive amount of ground, but besides the opening chapter, in which he frames the history of outrage, his narrative stops short of our current moment. Nesteroff writes cogently on documentaries and on podcasts, and therefore about the present—evidently, he has the commentary chops to “go there.” Perhaps a reason for his hesitation is the fact that contemporary outrage passes so quickly that by the time he finished writing the discussion, his examples had moved on. The last thing any author wants is for their commentary to look stale, an adjective I don’t think could ever describe Nesteroff’s work.

¤

That said, the past is prologue, and previous culture wars still have a lot to teach us about the present. There is no question that what we are seeing today in terms of fear, intimidation, and outrage has roots that go back generations. And for those who want to dive deeper, Matthew Dallek’s Birchers: How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right, released this year, offers a larger history of the movement as well as its connections to today’s political sphere. Indeed, each chapter of Outrageous encourages the reader to seek out more detail on our historical era of indignation, and Nesteroff’s intervention is one of stringing these cases together to establish his broader claims.

Nesteroff doesn’t explicitly tell us what to do with the knowledge he’s shared, and maybe he doesn’t have to. But I would argue that one thing we need to do is continue sharing the history of the culture wars. It’s why I teach the aforementioned class and am considering my own book on the subject. We need to expand conversation outside of the social media black hole where algorithms privilege the most idiotic content, and books like Outrageous give us a tool to share with others. Information, especially good information, is an undervalued commodity in today’s data-driven economy. If we are going to cut through the fearmongering around so-called “dangerous” popular culture, we first need to show that we can fight the outrage machine by exposing the hypocrisy of save the children–type rhetoric.

This book should spark useful conversations, even debate, by offering a template for discussing the relevance and origins of historic outrage culture. Nesteroff argues that outrage against popular culture often comes from a place of religious bigotry, is a generously funded venture, and is usually launched purely out of the desire to exercise political power. The fact remains that outrage is often funded and organized from above, is rarely centered on the artifact in question rather than the feelings around it, and remains just as important now as it was 100 years ago.