A Canadian woman has spoken for the first time about her marriage to one of the IS “Beatles” and her time living with him in Syria.

Despite global news coverage of savagery by the Islamic State (IS) group, Dure Ahmed claims she was “oblivious to what was going on” while her then-British husband El Shafee Elsheikh was committing atrocities.

He was part of a murderous IS cell linked to the abduction, torture and beheading of Western hostages.

The mother of two claims she wasn’t radicalised, but was just “a dumb girl in love”.

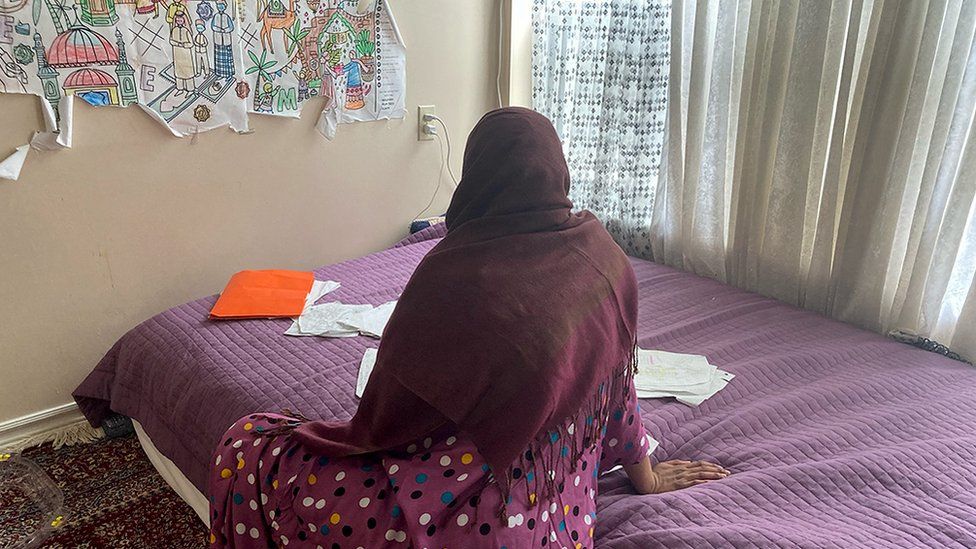

She agreed to answer questions from the BBC and Canadian broadcaster, CBC. “I’m not looking for sympathy or pity,” she explained.

Ahmed expects a backlash for speaking publicly, she says, but wants to highlight the plight of the women and children of suspected IS fighters still stuck in Syrian camps. She was held in such a camp for more than three years.

She says she now needs to accept that her time with Elsheikh was part of her life “whether I like it or not”.

Ahmed claims Elsheikh had not told her he had joined IS before she left to be with him. She insists she was unaware of the group’s jihadist ideology when she travelled from Canada to Syria in 2014. She claims she barely recognised the controlling and violent figure her now ex-husband had become.

Elsheikh and the others in his IS cell were nicknamed the “Beatles” by their captives because of their British accents. The men were responsible for the deaths of several hostages – most of whom were beheaded – with the deaths filmed and posted on social media.

At his 2022 trial in the US, prosecutors said Elsheikh’s actions resulted in the deaths of four Americans – journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and aid workers Kayla Mueller and Peter Kassig. They said he also conspired in the deaths of two British aid workers, David Haines and Alan Henning – as well as Japanese journalists Haruna Yukawa and Kenji Goto.

The bodies have never been found.

Elsheikh – from west London – is now serving eight life sentences in a US supermax prison.The UK stripped him of his citizenship before his conviction.

But, while he is in jail, questions remain about how much others – such as his wife Ahmed – knew about what IS were doing.

Ahmed joined Elsheikh in Syria two months after the murders carried out by his IS cell had caused outrage around the world. It was also just after IS had committed numerous atrocities while seizing the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, and started a genocide against Iraq’s Yazidi religious minority.

During Ahmed’s time out there, she gave birth to two sons. She and her boys were among a group of women and children repatriated to Canada in April.

The 33-year-old was arrested upon arrival on a “terrorism peace bond,” and later granted bail with conditions. On Monday, those conditions were reviewed in a court in Brampton, Ontario.

The Crown lawyer argued that Ahmed had been “steeped” in IS ideology and it would have been “likely” that she knew of her husband’s role with the group before leaving Canada in 2014.

The Crown and Ahmed’s legal team put forward a joint proposal with conditions that would include her being monitored by GPS – and being subjected to a curfew between the hours of 22:00 and 06:00. The judge said he would deliver his ruling on 19 October.

We interviewed Dure Ahmed twice – most recently in Toronto last week, where she spoke more freely. But our first meeting was in the detention camp in Syria last November. There, she had offered to speak to us about a missing British child we were searching for, as part of an upcoming BBC-CBC podcast series – Bloodlines.

At first, we had no idea of her husband’s identity – but, after investigating further we learned about the connection. We then wanted to know about Elsheikh’s radicalisation, his victims and his fellow IS “Beatles”.

Ahmed and Elsheikh met in Toronto in 2007. She was 17, he was 19. We asked how they had first connected as teenagers in Canada.

“Smoking weed,” she laughed. “He didn’t care about God, it was nothing to do with IS.”

The pair kept in touch when Elsheikh – the son of Sudanese refugees – returned to London. In 2010, they were married in an Islamic ceremony – but the relationship remained largely long distance, as Ahmed stayed in Toronto where she was studying for an English degree.

In London, Elsheikh became drawn to extremism and met the men who would become his fellow IS militants.

“He wasn’t a social person. He’s such an introvert. So he had all the qualities that can lead somebody into that dark path of radicalisation,” she explains.

In 2012, Elsheikh travelled to Syria to fight in the country’s civil war – he then joined IS. He was constantly encouraging his wife to join him.

“‘Come check it out. You could go back.’ As if it was so simple,” she told us.

Elsheikh refused to give her details of what he was doing in Syria – she claims – and says she didn’t even know which city he was living in.

“For the most part, I thought that not knowing was better than knowing.”

But, as she pondered making the trip, she claims members of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service – CSIS – questioned her about her husband.

“They [CSIS] did explain in Syria that there are things happening where it’s not as black and white as I thought it was. [But] they didn’t show me video.”

Ahmed claims she had nothing to tell CSIS and that she told Elsheikh that agents had contacted her. CSIS told the BBC it was not able to comment on the specifics of any case.

Bloodlines

As Islamic State group fell, what became of the children of its fighters?

Listen now on BBC Sounds

Ahmed was 24 and a jobless graduate when she did finally travel. She claims she had not seen the horrors of the IS beheadings which were being reported widely at the time. “It might be really hard to think, but it’s honestly the truth.”

We put to her that she was a smart woman who had been on a Middle Eastern studies course – surely she would have been aware of what was happening to Muslims across the world at that time?

“I distanced myself from what was happening in Syria,” she replied. Her study topics included the hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt, she told us, not current affairs.

According to Ahmed, Elsheikh arranged everything – all she had to do was “hop on a plane” to Turkey.

“I just carried a carry-on. Three pairs of pants and two T-shirts.”

In our years of reporting on IS, we’ve both found that most women don’t want to talk about why or how they got involved with the group. Everyone’s got their own story.

Some were victims of domestic abuse, some were duped or trafficked. Some came willingly as adventure seekers. Some followed their husbands and children. Some were children themselves.

And then, of course, there were all those women, who were committed, hard-core adherents to the IS ideology.

Ahmed denies having supported IS. In her answers to us, she preferred to paint herself as a naive romantic. When we spoke to her in the Syrian detention camp, she condemned IS – even though it was risky to do so in such a place.

Elsheikh and Ahmed lived in Raqqa – Islamic State group’s de facto capital in Syria – where summary killings at a city centre roundabout became commonplace, with severed heads put on display afterwards.

During our interview in the Syrian camp, Ahmed told us daily life had involved doing normal things with female friends, including going to restaurants or taking children on ferris wheels.

When we talked again – in the safety of Toronto – about life under IS rule, she denied Elsheikh’s prominent role allowed them to have a lavish lifestyle. In fact, she claimed, her house in Raqqa had felt like a prison – they rarely went out. No phone or internet – just her, her children and Elsheikh’s other wife. Polygamy was common. We asked if they’d had Yazidi slaves in the home – she said they hadn’t.

Her husband was “so private”, she claimed. “We couldn’t even pull up the blinds.”

She told us she believes her children are lucky to be alive, given the violence Elsheikh inflicted on her while she was pregnant.

Ahmed claims she tried to run away many times but her only option was to return – there was no family or support system under IS. She eventually left after he divorced her, seeking refuge with her boys in a guest house for women.

We pointed out that she had disclosed additional information during our second interview – and asked if it was just convenient for her to say these things now because she was back in Canada and at risk of going to jail.

“If I’m going to be charged, I’m going to get charged regardless. So it doesn’t really make a difference,” she replied.

Being physically away from Syria “looking at it from the outside… I think it just gives me more clarity”.

Elsheikh was captured in early 2018 by Syrian Democratic Forces, a US-backed Kurdish-led militia alliance, but it would be another year before Ahmed surrendered with her boys in the village of Baghuz – not long before IS made its last stand there.

Canada is one of the nations which has repatriated some of the families of IS fighters. The US, Spain, Sweden, Germany and France are doing the same.

The UK, meanwhile, has stripped citizenship from people who travelled to live under IS.

These individuals include Shamima Begum, one of the schoolgirls who went to Syria in 2015. She went on to marry an IS fighter and now lives in the same camp in Syria that Ahmed was in.

Leaving women and children in the Syrian camps, claims Ahmed, won’t help conquer the “radical path a lot of people go down”.

She claims she isn’t simply seeking to smooth her public image – but rather, she is speaking publicly because she is grateful she and her children have been given a second chance.

Elsheikh was convicted, but he had pleaded not guilty in court. Ahmed says he needs to admit what he did for the sake of his children and the families of his victims.

“This is something he has to talk to my kids about. It can’t just stop at his sentence.”

She claims that when court restrictions allow, she will speak to her ex-husband in jail – having offered to ask him questions on behalf of the victims’ families including the locations of their loved ones’ bodies.