SEDRO-WOOLLEY — More than a dozen shoppers mill around the Trader Joe’s-style shopping floor at Helping Hands Food Bank in Skagit County, filling up their carts with eggs, milk and locally grown produce.

In the attached warehouse, which occupies most of the 10,000 square-foot, barn-style building, volunteers in bright green t-shirts sift through piles of local produce. Each apple, each lemon, each head of lettuce is hand checked and crated for distribution. Items that don’t make the cut are set aside and given to local pig farmers for their hogs.

Powered by an about $500,000 grant, the food bank is reimagining the impact it can have in Skagit County, going beyond the traditional role of providing food to the community to also injecting funds into the agriculture sector by buying food directly from farmers.

Historically, food banks just take donations and redistribute to those in need, but Helping Hands wants to do more than that — it wants to be a “multiplier of good,” said CEO Rebecca Skrinde.

“The goal is to intentionally spend money locally,” Skrinde said. “Really showing the food banks as an economic development organization and not just a charity.”

The paradigm for food banks needed to shift as they are no longer able to rely on meeting increased demand through food donations and grocery rescue programs, Skrinde said.

“We have to purchase food,” Skrinde said, noting that Helping Hands now purchases about 50% of the food it gives away. “And if we’re going to purchase food, I want to do it in a way that can also show that we’re important to the economy of the county.”

In 2023, the food bank was awarded the We Feed Washington grant for its Skagit Human Investment Project, which commits the nonprofit to spending grant money on locally produced foods in 2024 and 2025 — the final years of the program.

We Feed Washington, administered by the state’s Department of Agriculture, was a pilot program launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; the goal was to bring emergency food from Washington-based producers to socially disadvantaged people experiencing hunger. The $35 million in biennial grants awarded in 2023 marks the end of funding.

Previously, money was directed to large food hubs that would then send boxes of produce to Helping Hands and other organizations fighting food insecurity in the state.

Money can now go directly to these organizations, allowing them to purchase locally-produced food —essentially keeping the food and money within the county, explained Skrinde.

The project allocates 70% of the grant’s funds toward local produce and about 30% of the money toward other foods from ranchers, dairies, fishermen and even local grain mills.

Working with Skagit farmers

Farmer Matt Steinman crouches down in his greenhouse to show off a flat of sprouting greens likely to be among the produce he supplies to the food bank this year.

Steinman — a first generation commercial farmer — took over his grandparents’ homestead farm more than a decade ago, quickly scaling it up to a production farm that feeds more than his family.

“We’re really lucky and blessed Helping Hands Food Bank is in the new location,” Steinman said, noting that the custom-designed building is less than a mile away.

The relationship between the food bank and farm started with Steinman donating any leftover produce, specifically lettuce, on his way back from one of the several farmer’s markets where he had a booth.

“That led to them wanting to buy more,” Steinman said.

Helping Hands started to buy radishes, squash, lettuce and other produce at a standard wholesale price, becoming a client that Steinman knew he could count on.

“We have a weekly, consistent, schedule,” Steinman said. “We know when they need food a couple days a week and so we have that ready for them.”

The purchased food arriving at the food bank is usually picked that day or the day before making it “restaurant quality,” Steinman said.

While Skrinde has often looked for opportunities to buy local, the reality is that when she has made significant purchases in the past, that produce has come from Chicago or Arkansas or somewhere else outside the state. The costs of buying local produce were prohibitive, she explained.

“But now, I have the ability to buy and tell the farmer, ‘I’m not looking for a cheap deal. I’m looking for what works for you,” Skrinde said.

She sees the food bank as an untapped market for the agriculture industry, as well as a way for farmers to mitigate risks knowing that Helping Hands will be there to purchase food when the market crashes around a crop, or if there is a bumper crop.

One example is a dairy producer just down the road from Helping Hands, who was being forced to dump milk because he couldn’t find a market for it, Skrinde said.

She sent a team member to see how they could help. The nonprofit agreed to pay the dairy for a set amount of milk every week, creating the type of consistency he could build a market around.

“What this grant does is it allows us to aggressively go out there and aggressively find them [farmers],” said Erik Larsen, the operations manager at Helping Hands, in charge of food procurement.

Steinman said some older, generational farmers have had their perception of the food bank challenged as it shifts from asking for handouts to being a market. Newer farmers have been much quicker to seize the opportunity.

A growing need for food

Helping Hands Food Bank saw a 40% increase in visits from 2022 to 2023, according to the nonprofit’s annual impact report.

“Last year alone, we saw 274,000 individuals come to one of our distribution (centers) or get food from us in one way or another,” said Larsen, noting that the food bank has six distribution points, as well as a mobile food service and other programs.

In many ways the food bank is able to fill the gap in social services between those who receive food stamps because they are at or below the poverty line, and those who are economically stable enough to cover the rising costs of living.

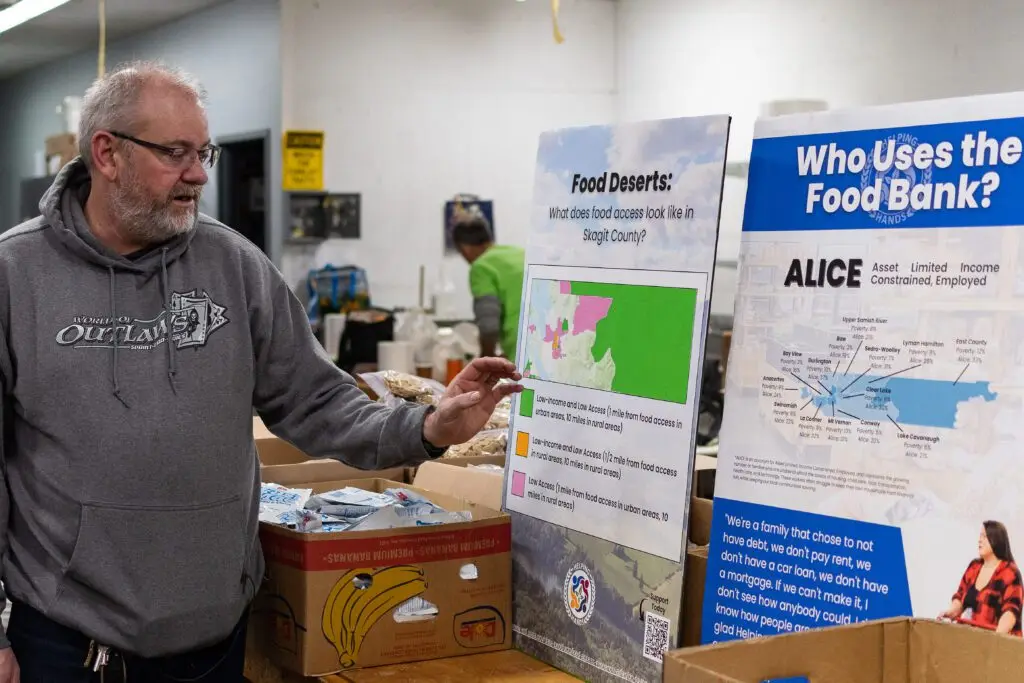

The residents who exist in this gap are often referred to as “Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed” (ALICE), which, unlike the national poverty line, factors in local costs of living.

“Our customer is someone who really doesn’t qualify for any kind of other help,” Skrinde said. “There’s no other parachute for them … So they are kind of forced to turn to food banks.”

Households in Washington are spending, on average, about $287 a week on groceries, according to an analysis of the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey data by HelpAdvisor.

A survey of more than 5,000 residents published in 2023 found that more than half of the respondents “used at least one type of food assistance in the past month.”

“Food price increases were felt by everyone, but households with food insecurity reported greater worry about price increases, as well as worse overall financial outlooks and more financial stress,” stated the survey report by WAFOOD4, a joint effort between the University of Washington and Washington State University.

Skrinde pointed out that people who have never navigated the food bank system before can feel completely adrift when they realize that their money won’t stretch far enough to put food in the cupboard.

“I hate to say that it’s because everything’s going up in price but in reality, everything is going up in price,” Skrinde said. “We just had a senior tell us last week that she feels like she’s starving in her house.”

Nearly 15,500 households in Skagit County were below the ALICE Threshold in 2019. That number rose to nearly 20,900 in 2021, according to the recent available data from United Way. The percent of ALICE households (29%) and households in poverty (11%) in Skagit County are both above the state’s average as of 2021.

The shopping floor of Helping Hands sees a wide variety of people seeking assistance, including Ukrainian refugees, migrant workers and so many others who are struggling to put food on the table.

“We have no barriers to access any of our services at Helping Hands,” Larsen said. “When they come in here, we treat them with dignity and respect.”

Isaac Stone Simonelli is CDN’s enterprise/investigations reporter; reach him at [email protected]; 360-922-3090 ext. 127.