Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Books

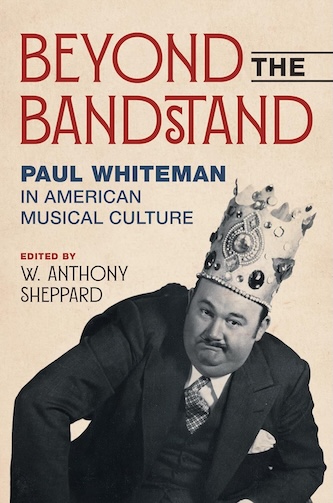

Raise your hands if you know who bandleader Paul Whiteman is. I see the hands of early jazz fans and probably no one else. But Whiteman was so well known between about 1920 and 1950 that, in 2072, it would be as if few recognized the names of Prince or Beyonce. For about 15 years, more people associated this musician with “jazz” than with any other person, including Duke Ellington or Count Basie. And therein lay the problem for jazz historians, who have not been kind to Whiteman.

Raise your hands if you know who bandleader Paul Whiteman is. I see the hands of early jazz fans and probably no one else. But Whiteman was so well known between about 1920 and 1950 that, in 2072, it would be as if few recognized the names of Prince or Beyonce. For about 15 years, more people associated this musician with “jazz” than with any other person, including Duke Ellington or Count Basie. And therein lay the problem for jazz historians, who have not been kind to Whiteman.

It’s very easy to make him a poster boy for cultural appropriation. His name itself for one thing. There is the fact that he never integrated his orchestras. And that Whiteman insisted that he was going to “make a lady out of jazz.” Still, his orchestras were admired by Louis Armstrong and Ellington. He used Black arrangers and never denigrated Black music or musicians. But Whiteman was tone deaf to the subtleties of race — a demerit in a figure who took up a considerable amount of cultural space.

Beyond the Bandstand: Paul Whiteman in American Musical Culture, edited by W. Anthony Sheppard (University of Illinois Press) addresses Whiteman’s career and status in eight essays and an afterword, all written by different people, almost all of whom are academics. The merits of the volume’s contributions range widely. One discusses how Whiteman’s large girth mapped onto race in the ’20s-’30s. The author’s premise: Whiteman appearance made it possible for white people to listen to music that would otherwise be associated with the hyper-sexualized image of Black people.

Another piece examines how the key Black music critic Dave Peyton saw Whiteman’s music. One essay, which includes musical examples, explores how Whiteman helped to codify “orientalism” in American music. Another addresses Whiteman’s time in Britain and Europe.

For me, the most striking contributions include one that placed Whiteman’s music in the continuum of “Modern American Music (MAM)” and one that addressed Whiteman’s role in the struggle to garner radio royalties for musicians. I hadn’t known of the important part that Whiteman played in the history of copyright and royalties.

Bottom line: some of the writers stretch a point too thin, but there’s also a lot of useful, interesting facts and ideas.

— Steve Provizer

In 1988, entertainer and dancer Jennifer Jones, a biracial woman, born and raised in Belleville, New Jersey, became the first African-American to perform with The Radio City Rockettes. (She debuted as a RCMH Rockette during Super Bowl XXII’s halftime show. She had a fifteen-year career with the troupe.) Her new memoir, Becoming Spectacular: The Rhythm of Resilience from the First African American Rockette (Harper Collins), is a straightforward chronicle of the effort it took to break through the prejudice of the RCMH Rockette management and join this most famous of lineups. Jones writes that her success was propelled by “preparation plus opportunity.” Ironically, what makes Jones’ narrative so compelling is just how matter-of-fact it is. Jones is a cultural trailblazer, but there is no preening about it. She does not see herself as a Civil Rights icon or even classify herself as a particularly noteworthy representative of Black culture. Jones is content to portray herself as a hard-worker, a dancer who persevered and sacrificed to perfect her craft and establish a career.

In 1988, entertainer and dancer Jennifer Jones, a biracial woman, born and raised in Belleville, New Jersey, became the first African-American to perform with The Radio City Rockettes. (She debuted as a RCMH Rockette during Super Bowl XXII’s halftime show. She had a fifteen-year career with the troupe.) Her new memoir, Becoming Spectacular: The Rhythm of Resilience from the First African American Rockette (Harper Collins), is a straightforward chronicle of the effort it took to break through the prejudice of the RCMH Rockette management and join this most famous of lineups. Jones writes that her success was propelled by “preparation plus opportunity.” Ironically, what makes Jones’ narrative so compelling is just how matter-of-fact it is. Jones is a cultural trailblazer, but there is no preening about it. She does not see herself as a Civil Rights icon or even classify herself as a particularly noteworthy representative of Black culture. Jones is content to portray herself as a hard-worker, a dancer who persevered and sacrificed to perfect her craft and establish a career.

Jones poignantly depicts her average, middle-class upbringing. Her mother and father, an interracial couple during the age of Loving vs. Virginia, encouraged their daughter’s dream of becoming an artist. While in school, Jones performed in a dance recital that supercharged her love of performing. She went on to attend the Phil Garcia Dance School, where she excelled. She saw the 1974 all-Black production of The Wiz on Broadway and the experience proved to be pivotal. Professionally and personally, she experienced racism (even when she was a Rockette, there were moments), but these outrages are not as much of a focal point in the book as is her life as a performer.

Her post-Rockettes career has been busy. Despite being a vegetarian, Jones became an advocate for health education in the Black community after she was diagnosed with stage 3 colorectal cancer in 2018. In 2023 she penned a children’s book, On the Line: My Story of Becoming the First African American Rockette. Her reminiscences in Becoming Spectacular underline the dancer’s admirable determination; through all of the dancer’s ups and downs, Jones has remained a consummate trouper.

— Douglas C. MacLeod

Few places on earth have become so deeply associated with a single architect as has Barcelona with its brilliant native son, Antoni Gaudi. The bunched spires of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia basilica are now the most recognizable symbol of the city and the architect’s major works there— the Casa Milla apartment building, the facade of the Casa Battlo on the Passeig de Gracia, the lavish Palau Guelph, and the fantasy kingdom of the Park Guell, are obligatory stops in the now overwhelming tourist traffic to this unparalleled city.

Michael Eaude’s Antoni Gaudi is a short (190 pages), small format book (Reaktion Books) intended for general audiences: non-specialists who want to know more about the man who so shaped his city’s distinctive image. Engagingly written, it is no coffee table tome; the illustrations are small and black-and-white. Yet Eaude’s treatment seems complete and thorough, tracing the architect’s youthful sense of self to the medieval Counts of Barcelona. He is particularly good on Gaudi’s relationship to his patrons, most of them drawn from the city’s india class— entrepreneurs who fled the economic constraints they faced in Spain to make their fortunes on slave plantations in the West Indies. Returning home, they invested that money in Catalan industries, especially textiles, showing off their wealth with Gaudi’s strikingly original town houses and estates.

In his youth, Gaudi had anarchist sympathies. He remained fiercely devoted to the cause of Catalan rights. As he aged and grew famous, he became increasingly conservative and religious. When other work stalled, he focused on his lifelong obsession, the Sagrada Familia. People crossed the street to avoid his appeals for construction funds. When he was struck down by a tram in June 1926, his clothes were so ragged he was taken to a charity ward. He died three days later.

— Peter Walsh

Artist Edward ‘Ted” Gorey (1925-2000) was a dream of a pen pal. When he and his friend Tom Fitzharris exchanged letters over the course of 1974 and 1975, Gorey decorated the exteriors of his 50 envelopes with his trademark cobwebby ink drawings, their playfully macabre or fantastical scenarios often featuring two dogs gamboling, each with a T tattooed on his body. The missives included typewritten letters detailing the artist’s amusing if cranky news or gossipy views (we are given excerpts) along with handwritten note cards containing memorable/odd quotations from the famous (Wallace Stevens, Ezra Pound, Borges) and the obscure (Trumbull Stickney, Sandys Wason). Also in the epistolary mix: limericks, color postcards, and choice bits of antique paper flotsam, such as a nineteenth century pew ticket.

From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey, edited and with an introduction by Fitzharris (New York Review Books, 248 pages) is chockablock with eccentric delights, from Gorey’s surreal, Victorian-tainted illustrations (the dogs stand on swings, perform circus acts, balance on the sun, cruise in balloons) to his self-deflating humor, which is often aimed at his lethargic condition:

There was some subject of high import I meant to deal with this morning but I do not recollect what it was. I still haven’t done the envelope. Time is passing. None of us is/was getting any younger. What does it all mean? We are temporarily out of oreos. Oh God.

The literary quotations are a blast. Some are for real (“Our own journey is entirely imaginative. Therein lies its strength” — Céline). Some are misattributed: Ezra Pound didn’t write “Toujours les tripes” — it was Paul Valéry. Fitzharris writes in his Introduction that Gorey read widely throughout 19th century literature (he explains some of the correspondence’s inside jokes in a Notes section). That appetite is obvious: there are two quotations from a relatively obscure favorite novel of mine — George Gissing’s The Nether World, his 1889 saga about the misery of London’s poor and the limits of well-meaning altruism.

— Bill Marx

Anyone starved for old-fashioned storytelling rather than trendy gimmicks (peek-a-boo autofiction, chapterettes) will pounce on A Walker in the Evening (Ruby Violet Publishers, 264 pp), from seasoned book commentator Nick Owchar (L.A.Times et al.).

The Walker is Mikaylo, or Michael, or — Yuri when he sets out in June, 1909, a gouty farmer carrying a devilishly grinning carved totem, on his annual nightwatch duty in a Galician village. Mikaylo when born in England to immigrants, Michael in the priesthood, Yuri as we meet him.

Who am I? Where do I belong? Universal questions rendered more urgent by the immigrant experience. Secrets from Yuri’s past surface, piecemeal, in his internal monologue, while the present night teems with worries over his wife, malevolent rowdies, and hallucinated ghouls his totem must disperse — or are they all imaginary?

The parallel structure allows for riveting period drama. A craze for table-tipping and spiritualism rubs shoulders with the restoration of English Catholicism. Father Michael plays fast and loose with ritual and terminology and theological borderlands. Fictional characters mingle in Mayfair with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Swinburne, and a revisionist theory of Dante. Owchar, while authoritative, is the opposite of pedantic. Yuri is warm-hearted, and a properly self-doubting Catholic. Despite some motivational stumbles along the way (was so much guilty secrecy really necessary?) Walker fulfills its promise.

One might call A Walker in the Evening, inspired by Owchar’s own family history, an historical novel with a Gothic twist — or, a period speculative novel with a long reach. Yuri’s village is within the Austro-Hungarian Empire and populated by Ruthenians, members of an ethnic group with a language of its own, already used to being pushed around by Poles, Russians, and Hungarians. In other words, the people of today’s Ukraine: “The dream we have of a country of our own, of Ruthenia, can’t be far away. It’s coming. I can feel it.”

— Kai Maristed

Young French journalist Louisa Yousfi hasn’t the eloquence of the James Baldwin who wrote The Fire Next Time, but her pugilistic essay collection, In Defense of Barbarism: Non-Whites Against the Empire (Verso, 112 pages, translated by Andy Bliss), shares his fury at the delusive promises of integration. She points to the agonizing plight of Blacks and Arabs in France, ‘barbarians’ made to feel ashamed of their culture by white society’s demands that they ‘fit in’. She dares to ask — who are the real savages in this arrangement? Like Baldwin, she flips the script, arguing that the brokers of Empire wield assimilation as tool to homogenize, criminalize, and deaden the Other: “… deep down, what they are afraid of is not that we might lack humanity, culture, or a moral sense, but the precise opposite. They are afraid of that part of us that cannot be assimilated, which is to say our history, our culture, our souls.” How should the oppressed respond to the dangers of civilization? Nurture the affronted saintliness that resists acculturation: “the Baldwinian fire within us, which threatens to burn down everything, has to be kept under control without ever being allowed to go out. It has to remain a private barbarian spark that gives us courage for the struggle, sometimes against the fire itself.”

Young French journalist Louisa Yousfi hasn’t the eloquence of the James Baldwin who wrote The Fire Next Time, but her pugilistic essay collection, In Defense of Barbarism: Non-Whites Against the Empire (Verso, 112 pages, translated by Andy Bliss), shares his fury at the delusive promises of integration. She points to the agonizing plight of Blacks and Arabs in France, ‘barbarians’ made to feel ashamed of their culture by white society’s demands that they ‘fit in’. She dares to ask — who are the real savages in this arrangement? Like Baldwin, she flips the script, arguing that the brokers of Empire wield assimilation as tool to homogenize, criminalize, and deaden the Other: “… deep down, what they are afraid of is not that we might lack humanity, culture, or a moral sense, but the precise opposite. They are afraid of that part of us that cannot be assimilated, which is to say our history, our culture, our souls.” How should the oppressed respond to the dangers of civilization? Nurture the affronted saintliness that resists acculturation: “the Baldwinian fire within us, which threatens to burn down everything, has to be kept under control without ever being allowed to go out. It has to remain a private barbarian spark that gives us courage for the struggle, sometimes against the fire itself.”

Alongside the political analysis there is cultural criticism, some of it meant to goad. The End of the Primitive, Chester Himes’ censored 1956 novel about a Black man who kills his white lover, is praised for its incendiary inversion of “the conventional hierarchy of values.” An essay on the French rapper Booba, however, ends up idealizing the artist — “an impenetrable power from the limbo of civilization.” We were told earlier in the book that barbarism must be tempered, not automatically praised. Predictably, Yousfi is better on the articulate attack than positing concrete alternatives. By all means, critique a racist system that compels humiliation, but how will that fiery rage be modulated? And by who? Still, Yousfi is an enlivening combatant who lives by Ishmael Reed’s magisterial dictum: writin’ is fightin’.

— Bill Marx

Visual Art & Design

Studio IKD’s proposed public art project for Cambridge’s Tobin Montessori and Vassal Lane Upper Schools complex.

A living piece of public art will be growing in Cambridge for years to come. The memorial to a beloved apple tree previously removed at a public school will take a hybrid form: part children’s playscape, part tree. This thoughtfully functional piece of public art will be integrated into our natural environment. Yet the piece’s sense of play, rooted in a celebration of community history and joy, also embraces the design challenges posed by what we are collectively doing to the planet.

One of the aims of The Community Grafting Project, a public art/environmental healing strategy commissioned by Cambridge from the Somerville-based architectural and design studio IKD, is to give the original tree new life. The new apple tree will be surrounded by a wood playscape structure that cleverly symbolizes the curves of tree roots. Part of the structure will be fabricated from wood salvaged from trees that were cut during the school’s construction. An exhibit at Gallery 344 (344 Broadway, Cambridge, through February 7) illustrates what IKD is up to: public art that stresses the connections between science, art, and society. The show supplies a compelling overview of the creation of the project. Texts explain how grafted apple tree buds are nurtured, accompanied by photos, drawings, and wood samples that were studied for their aptness to become part of this playscape structure.

This public art project will restore a gathering place that was lost when the apple tree was removed while it also celebrates community and expands the notion of what is public art. Unlike many aspirational proposals, this plan to improve our shared environment, led by Yugon Kim and Tomomi Itakura, is going to become a reality. Combining functional public art with environmental stewardship, it is part of the City of Cambridge’s commitment to plant hundreds of new trees at the school. So, there will always be apples available to pick for teachers. Bravo!

— Mark Favermann

Popular Music

Nigerian producer Seo is restless. It’s evident from her hyper-productive pace — she turned out four EPs and albums in 2024. Seo been working this hard for the last 6 years, and that restiveness is apparent in her music. Although she has been described by critics as a practitioner of bedroom pop, Seo’s style defies easy labels. Her approach embraces sonic imperfections — Seo doesn’t believe in smoothing rough patches over. Her vocals can be read as pop — comparable to artists like Pink Pantheress — but she exploits tape hiss as if it were just another one of the instruments at hand. Harmonies and rhythms don’t line up the way they’re “supposed to.” Instead, the tunes tap into a helter-skelter maelstrom of churning feelings.

Nigerian producer Seo is restless. It’s evident from her hyper-productive pace — she turned out four EPs and albums in 2024. Seo been working this hard for the last 6 years, and that restiveness is apparent in her music. Although she has been described by critics as a practitioner of bedroom pop, Seo’s style defies easy labels. Her approach embraces sonic imperfections — Seo doesn’t believe in smoothing rough patches over. Her vocals can be read as pop — comparable to artists like Pink Pantheress — but she exploits tape hiss as if it were just another one of the instruments at hand. Harmonies and rhythms don’t line up the way they’re “supposed to.” Instead, the tunes tap into a helter-skelter maelstrom of churning feelings.

Seo’s latest album, Bloodberry, begins with a swing away from the electronic beats of her recent efforts. The unstructured guitar strumming that’s spotlighted in the 14-minute “The Freedom” lays down a gauntlet for the listener. The second song, “Bluebird,” takes a far more appealing tack, and that continues for the rest of the album. Her move from intimate singing to rapping — as a distant drum machine crackles — is exhilarating on “Bluebird”. “The Choire,” an atonal acapella instrumental, layers Seo’s voice to build a spectral dissonance. Other songs carve out murky yet catchy melodies. “Tumbleweed” taps into melancholy by contrasting Seo’s moody vocals with squelchy synthesizers.

Bloodberry’s energy stems from how it does not make everything line up neatly. Seo shuns Autotune and quantization; she flirts with pop and R&B while retaining the outlook of a skeptical outsider. (The title track’s piano chords and ticking drum machine could pass for a rough SZA demo.) “Paco Rabanne” fantasizes, ironically, about what it would be like to live the glamorous life: “Nollywood babes, Nigerian drapes/cash makes everywhere sweet escape.” But there is nothing artificial about Bloodberry — its strengths lie in its loyalty to the same personality across an eclectic approach to genre. As different as Bloodberry‘s songs are, they’re all recognizable as creative effusions of Seo.

— Steve Erickson

Classical Music

When you put Joshua Bell, Steven Isserlis, and Jeremy Denk in a room together, sparks are bound to fly. They certainly do –though not always as you’d expect — in the group’s traversal of Felix Mendelssohn’s two piano trios (Sony Classical).

Musically, these are impressively balanced performances, the musicality of the virtuosi far exceeding the sum of their individual parts (and, it would seem, egos). This comes out most captivatingly in the Trio’s respective scherzos. Those movements are as stereotypically Mendelssohn as you can get: brilliant, precise, full of rigorous but light-footed counterpoint.

Here the collective delivers those sections with all the fleetness one expects of them. But their discreet turns to the shadows within them highlight the subtle relationships these seemingly carefree sections have with their neighbors on either side. As a result, these are compellingly full-bodied scherzos, cathartic and playful to be sure, but also expressively three-dimensional and offering more than the usual dash or two of acid.

The works’ remaining movements are a picture of exquisite collaboration, Bell and Isserlis trading off the music’s mix of lyricism and fragmentation with aplomb; their unison episodes — like the refrains of the big tune in the D minor’s finale — always brilliantly matched.

Denk anchors the proceedings with understated precision. To be sure, he’s exactly the pianist you want to hear playing these involved parts. The flurries of accompanimental figures that bustle about in the background are just as meaningfully shaped as the Trios’ solo keyboard moments. In those (especially the beginnings of both Trio’s slow movements) you can just sit back and relax: throughout this set, you’re in very good hands.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Philadelphia is a major center of musical creativity. A new CD (Centaur CRC4103) brings us shortish works (averaging 7 minutes each) for string orchestra by seven area composers, beginning with the most famous, Richard Danielpour, and including three women. The works are performed by the ensemble that commissioned them: Chamber Orchestra First Editions, under its founding conductor James Freeman. (Freeman, an Emeritus Professor of Music at Swarthmore College, is perhaps best known for having conducted Philadelphia’s highly enterprising Orchestra 2001 for twenty-seven years. He is also a remarkable pianist, whose insightful recorded performances I have praised here, here, and here.)

Philadelphia is a major center of musical creativity. A new CD (Centaur CRC4103) brings us shortish works (averaging 7 minutes each) for string orchestra by seven area composers, beginning with the most famous, Richard Danielpour, and including three women. The works are performed by the ensemble that commissioned them: Chamber Orchestra First Editions, under its founding conductor James Freeman. (Freeman, an Emeritus Professor of Music at Swarthmore College, is perhaps best known for having conducted Philadelphia’s highly enterprising Orchestra 2001 for twenty-seven years. He is also a remarkable pianist, whose insightful recorded performances I have praised here, here, and here.)

The CD cannily arranges all seven pieces into a kind of arc, for people choosing to listen at a single sitting. “A Simple Prayer”, by the prolific Richard Danielpour, begins the voyage with melodious gentleness, reminiscent of some of the great English pieces for string orchestra by Elgar and Vaughan Williams. “Time Diverted”, by organist and choir director Jay Fluellen, explores a more energetic mood evoking neoclassical Stravinsky. Cynthia Folio’s “Pentaprism” then yanks us into more frankly modernist sounds, complete with Bartókian “snap” pizzicatos and a tight five-note motive that gets introduced, manipulated, and then gradually disappears, one note at a time.

Jan Krzywicki provides the CD’s “scherzo” in his engaging, ever-surprising “Capriccio”. Ingrid Arauco follows with the touching, sometimes yearning “Via cordis”, “inspired by Henri Nouwen’s short, elegant book The Way of the Heart, which explores the teachings of the Desert Fathers.” Heidi Jacob’s fresh-as-a-daisy “Many in One” displays and contrasts the many possibilities of a string ensemble: a solo violin, the second violins performing in unison, and so on. Robert Maggio brings things to a close, somewhat the way that Danielpour began it, with the life-affirming “Bright Elegy”, based on a Sicilian lullaby.

— Ralph P. Locke

Paavo Järvi’s recorded tenure in Zürich has already resulted in a series of invigorating albums showcasing the standard canon in new lights. Here it continues into the 20th century with a fresh approach to Carl Orff’s popular Carmina Burana.

Clarity and energy are the names of the game, with little details emerging all over, like the crisply present (and audible!) bass drum grace notes in “O Fortuna” and the wonderful sense of space in “Olim lacus.” Also, the music’s debts to Stravinsky (especially Les Noces) come out strongly in the reading’s pristine delivery of Orff’s writing for percussion instruments.

But Järvi, the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Zürcher Singakademie, and Zürcher Sängerknaben don’t just settle for surface charms here. Rather, they dig into the score’s larger plays of contrast with brio. The choirs’ diction is precise and clean, their shaping of phrases gamely highlighting the meanings of texts, be they playful (“Floret silva”), erotic (“Tempus est iocundum”), or tipsy (“In taberna”).

Soprano Alina Wundelrin is the star of the disc’s three soloists, effortlessly floating her stratospheric moments — “Dulcissime” gleams — and blending beautifully with the pure-toned children’s chorus in “Amor volat undique.” Countertenor Max Emauel Cencic intones the lament of the roasting swan with warmth, though a bit less intensity than one typically gets from a tenor straining through the role. For that experience, you’ve got to wait a few tracks for baritone Russell Braun’s wonderfully exacting traversal of “Dies, nox et omnia.”

Alpha’s sonics are bright and sometimes a bit resonant. But everything is balanced well and the excitement of Järvi’s reading is palpable. Who knew we needed another recording of Carmina Burana? This one fully justifies itself.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

It’s back to Brahms — and even further back to Schubert — for pianist Alexandre Kantorow, whose new solo album (BIS) pairs the former’s Fantasy in C with the latter’s Sonata No. 1, while bridging the gap by way of five of Franz Liszt’s arrangements of Schubert songs. If that sounds like a lot, it is, and not just in terms of notes, technical and expressive demands, or style.

It’s back to Brahms — and even further back to Schubert — for pianist Alexandre Kantorow, whose new solo album (BIS) pairs the former’s Fantasy in C with the latter’s Sonata No. 1, while bridging the gap by way of five of Franz Liszt’s arrangements of Schubert songs. If that sounds like a lot, it is, and not just in terms of notes, technical and expressive demands, or style.

The Brahms and Schubert numbers share more than a few characteristics, both in terms of mood and musical content. The French pianist ably teases all of those out. His sense of rhythm in the Fantasy is ever secure and taut and, while his phrasings can border on the rhetorical, the music’s contrapuntal dialogues never lack for tension. What’s more, parts of his reading—like the first movement’s development—build to winningly blustery apexes.

Though the Brahms Sonata was published as his opus 1, there’s little about it that sounds youthful or inexperienced, at least in Kantorow’s hands. Rich-toned, well-balanced, and poetic, the pianist sometimes takes his time—the Andante feels a touch spacious—but never at the expense of character or drama. Instead, his exceptional musicianship illuminates Brahms’s sometimes ferocious part-writing from within.

Meanwhile, the Liszt selections — “Der Wanderer,” “Der Müller und der Bach,” “Frühlingsglaube,” “Der Stadt,” and “Am Meer” — remind that Schubert wasn’t just the domain of the 19th-century’s conservative musical factions. As goes for the bigger works, each of these are grippingly played, especially “Der Wanderer,” the bass line of which takes on a life all its own.

— Jonathan Blumhofer