Scientists need skills in visual analysis and critical thinking, but these skills aren’t being taught or practised nearly enough in our university classrooms.

(Lee Nachtigal/Flickr), CC BY

One reason why science is hard to learn is because it relies on visuals and simulations for things we cannot see with the naked eye. In topics like chemistry, students struggle to translate complicated symbols to the atoms and molecules they are meant to represent.

Surprisingly, most university chemistry classrooms are not helping students with these tasks. Students spend lectures passively viewing slides packed with images without engaging with them or generating their own. Relying on innate ability, rather than teaching visual thinking and analysis skills, leaves many students feeling lost in the symbols and resorting to arduous and unproductive memorization tactics.

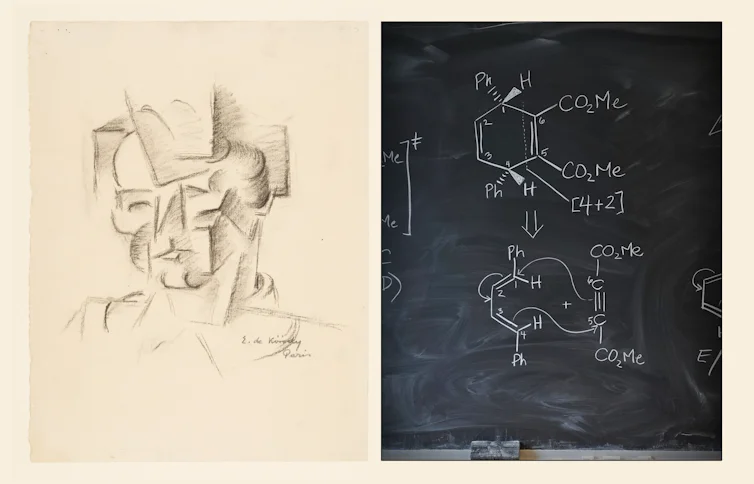

What can we do to help students analyze and learn from scientific visuals? Fortunately, we can look to the arts for inspiration. There are parallels between the skills learned in art history and those needed in science classrooms.

Developing a trained eye

Feeling baffled by a work of art is similar to the experience of many chemistry learners. In both scenarios, viewers might ask themselves: What am I looking at, where should I look and what does it mean?

And while a portrait or landscape may seem straightforward in its message, these works of art are filled with information and messages hidden to the untrained eye.

The longer a viewer takes to look at each image, the more information can be uncovered, and the viewer can ask more questions and explore further.

For example, in the 18th-century painting Still Life with Flowers on a Marble Tabletop by Dutch painter Rachel Ruysch, looking beyond the flowers painted in full bloom reveals a swarm of insects, which art historians regard in a wider context of spiritual meditations upon mortality.

(Rijksmuseum)

The field of art history is dedicated to exploring works of art, and emphasizes visual analysis and critical thinking skills. When an art historian studies a work of art, they explore what information may be contained within the work, why it was presented in that manner and what this means in a broader context.

Read more:

Mike Pence’s fly: From Renaissance portraits to Salvador Dalí, artists used flies to make a point about appearances

Process of looking, asking questions

This process of looking and asking questions about what you are looking at is needed at all levels of science, and is a useful general skill.

The non-profit organization Visual Thinking Strategies has created resources and programs to support educators, from kindergarten to high school, in using art for discussion in their classrooms.

These discussions about art help young learners develop skills for reasoning, communicating and coping with uncertainty. Another resource, “Thinking Routines” from Harvard’s Project Zero, includes more suggestions for leading engagement with art and objects to help students cultivate observation, interpretation and questioning.

Critical viewing means slowing down

Such approaches have also been embraced in medical education, where medical students learn critical viewing through close-looking activities with art, and explore themes of empathy, power and care.

(Shutterstock)

Medical humanities programs also help young professionals to respond to ambiguity. Learning how to analyze art changes how people describe medical images, such as photos of clinical interactions, and has been shown to improve their empathy scores.

The skills needed for visual analysis of art works require us to slow down and let our eyes wander and brains think. Slow and deep looking involves taking four or five minutes to silently view a work of art, allowing surprising details and connections to surface. Students training in medical imaging in the field of radiology can learn this slow and critical viewing process by interacting with art.

Students in classrooms

Now imagine the difference between a leisurely setting like a gallery to a classroom, with the pressure to listen, look, copy and learn from visuals and prepare for exams.

How long are students spending analyzing these complex chemistry diagrams? Research that colleagues and I conducted suggests very little.

(Mikhail Nilov/pexels)

When we observed chemistry classrooms, we found that students either passively viewed images while the instructor discussed them, or copied visuals as the instructor drew them. In both cases, they are not engaging with the visuals or generating their own.

When teaching chemistry, Amanda, the lead author of this story, has seen students feel pressure to find a “correct” answer quickly when solving chemistry problems, causing them to overlook important but less obvious information.

Visual analysis in chemistry education

Our team of artists, art historians, arts educators, chemistry teachers and students is working to bring arts-inspired visual analysis into university chemistry classrooms.

Through mock lectures followed by in-depth discussions, our preliminary research has found intersections between the practices and teachings of the visual arts skills and the skills needed for chemistry education, and we’ve designed activities for teaching students these skills.

A focus group with university science educators helped us refine the activities to work for educators’ classrooms and goals. Through this process, we’ve identified new ways of thinking about and engaging with visuals and as our research evolves, so may these activities.

Many students in university science classrooms will not pursue a traditional career in science, and their programs rarely lead to a specific job, yet visual thinking skills are essential in the wide skill sets needed for their future careers.

Visual analysis and critical thinking are becoming even more important in daily life now with the rise of AI-generated images and videos.

Developing skills to slow down and look

Integrating the arts into other disciplines can support critical thinking and introduce learners to new perspectives. We argue that the arts can help science students develop essential visual analysis skills by teaching them to slow down and simply look.

“Thinking like a scientist” has come to mean asking questions about what you see, but this could easily be framed as thinking like an art historian:

-

Look closely for details;

-

Consider details together and in context (for example, by asking: “Who created this and why?”);

-

Recognize the need for broad technical and fundamental knowledge to see the less obvious, and;

-

Accept uncertainty. There may be more than one answer, and we may never know for sure!