Rebecca Flitcroft is on a quest. And she wants you to join her.

As a research fish biologist with the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, she cares about water a lot. Specifically, she wants to shine a light on the need for freshwater protection because biodiversity in freshwater is declining at an alarming rate. To address this critical issue, Flitcroft and her colleagues were recently published in Nature Sustainability for their article, “Making Global Targets Local for Freshwater Protection.”

Attention to freshwater is more vital now than ever to protect freshwater ecosystems worldwide. Global freshwater conservation needs to be addressed like sewing a quilt. Targets can only be achieved through a consistent local patchwork of freshwater protection efforts stitched together to compose a global network that blankets every continent on our planet.

But why should the public care? And why should they care now?

Flitcroft explains: “Diversity equals resiliency for ecosystems and people. Biodiversity is our resilience for climate change.”

To address this critical issue, Flitcroft and colleagues were recently published in Nature Sustainability for their article, “Making Global Targets Local for Freshwater Protection.”

Most of us turn the faucet and water bursts forth instantly—and that’s often as much as we think about freshwater. However, our tap is connected to diverse worlds of freshwater-dwelling creatures. These wonderous, innumerable creatures add to the fortitude of ecosystems, planetary health, and food supply diversity.

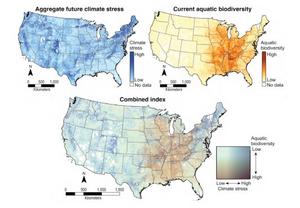

As climate change intensifies, it can negatively affect areas of aquatic biodiversity. Above, the map shows overlap of projected high future climate change stress and areas of high aquatic biodiversity. These are the areas that need critical freshwater protections in place to protect ecosystem diversity.

According to Flitcroft, freshwater from forests provides clean water to downstream users. Interconnected and clean sources of freshwater provide significant protein resources globally. Freshwater biodiversity is declining at a faster rate than in any other environment, and biodiversity is a buffer for ecosystem function as environments change. If freshwater ecosystems are to continue providing clean water and food, biodiversity needs to be protected.

By 2030, conservationists aim to have 30 percent of Earth’s lands, seas, and inland waters under effective protection . This so-called 30 x 30 goal of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework is the product of a 2022 United Nations’ biodiversity conference. It’s a complicated prospect to protect a percentage of the world’s water, yet scores of countries agreed to the goal, which targets areas of high biodiversity and ecosystem function for protections.

According to Flitcroft, the “biggest challenge to freshwater conservation is the complexity of the issue.” Unlike lands on which a boundary can be drawn around a specific habitat type, rivers connect headwaters to larger rivers that drain into lakes, reservoirs, wetland complexes, or oceans. Every part of all landscapes is or has been affected by water in some form at some time.

This makes developing freshwater protections difficult—from strategizing where the protections should go and what processes, species, or ecosystem services to target, to creating conservation methods. Another major hurdle is assessing whether those protections are working.

Flitcroft and colleagues’ study findings suggested that a combination of protections would likely be needed to cover the complex river networks that compose a complete, interconnected aquatic system.

Conservation on the scale outlined in the Global Biodiversity Framework’s 30 x 30 goal can be a daunting prospect—but not impossible. In fact, there are ways that even average citizens can join this quest.

Think your backyard.

“There are a lot of opportunities for people to get involved in aquatic conservation,” Flitcroft suggests. “Watershed councils and water groups are available and looking for volunteers to help in applied work—literally in your own backyard. At a global conservation level, volunteers are the backbone of the International Union for Conservation of Nature—World Commission on Protected Areas (IUCN WCPA).”

Study authors:

- Rebecca Flitcroft (Pacific Northwest Research Station)

- Robin Abell (The Nature Conservancy)

- Ian Harrison (Conservation International)

- Ivan Arismendi (Oregon State University)

- Brook E. Penaluna (Pacific Northwest Research Station)

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not responsible for the accuracy of news releases posted to EurekAlert! by contributing institutions or for the use of any information through the EurekAlert system.