They worked together for 20 years and became close friends. Despite increasingly grim news from medics, George Alagiah’s spirit remained indomitable – writes Sophie Raworth.

I have a daughter called Georgia. She is 17 years old. In November 2005, on the day she was due to be born, my husband and I walked into a Moroccan-style tent in a back garden in north London. It was filled with bunting, long tables, food and George Alagiah’s whole family – his wife and two sons, his father, four sisters, nieces, nephews and a handful of close friends. It was his 50th birthday party. A small, intimate affair for a man who adored his family more than anything else. When my baby finally appeared two weeks later, we named her Georgia after him.

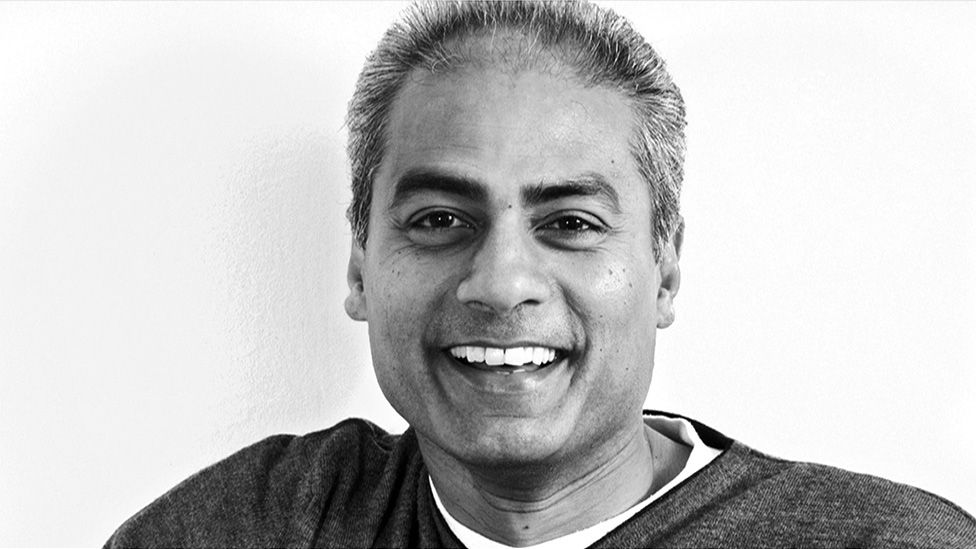

George had a rich spirit. He radiated warmth with a wonderful smile and a velvety laugh. I first worked with him in January 2003 when we launched the new BBC Six O’Clock News, sitting side by side in the studio at Television Centre in west London. He was a foreign correspondent at heart. That was his passion. He loved being out on the road, telling other people’s stories. But he also felt enormously proud to be asked to present the BBC TV’s main news bulletins – and he felt a real connection with the audience.

He was terrible with technology. We would laugh for hours in the newsroom as I tried to help him grapple with sending a text or photos on his new mobile phone – or working his way around his computer. But he was brilliant with words and when it came to stories he had such a fine sense of judgement.

George was a man of great empathy. In the newsroom he was adored and admired by the team of producers behind the scenes. He was a true team player. He wanted to listen to everyone’s opinion and never assumed he was right. A man without ego – unusual in the TV world – he never wanted the story to be about him. And then, suddenly, it was.

George was diagnosed with stage 4 bowel cancer in April 2014 at the age of 57. He texted me one evening. “Sophie, I know you’re on holiday but could we have a chat? G x” – George always texted before calling. He never wanted to bother people.

The cancer had already spread to his liver. I sat on the floor listening. We talked for ages. “I just hope I am here and able to have a conversation with you in five years time,” he said before hanging up. I went online. The statistics didn’t look good – just a 10% chance that he would be.

I flew to America a few days later to run the Boston Marathon. It turned into a run for George. In just a couple of days I had raised almost £10,000 for a bowel cancer charity. So many people wanted to do something for him. It was a year after the Boston Marathon bombing. The words “Boston Strong” were written everywhere across the city. I flew home to London with a Boston Strong T-shirt and my medal in my bag – and gave him both.

During the following months of gruelling chemotherapy and then major operations, he took the medal with him and wore it for luck. When the treatment was finally over 18 months later, he returned to work and returned my Boston medal to me. He’d had it framed with a picture of him and his wife in the middle, wearing their Boston Strong T-shirts. It’s on the wall in my kitchen by the fridge. I smile at it every day.

Exactly five years after George had first called me to tell me about his cancer, we went for lunch on a sunny terrace in London to celebrate still being able to chat. He was back at work, looking good. George rarely spoke publicly about having cancer. He said he didn’t want to give a running commentary about his illness. But when he did give interviews, he was always taken aback to find himself on the front page of newspapers. He never understood the interest in him and just how much people wanted to hear his story.

George Alagiah remembered

- BBC newsreader George Alagiah dies aged 67

- Empathy was George’s great strength, he radiated it

- Live: Tributes paid to ‘brilliant broadcaster’

- Watch: George Alagiah’s extraordinary career

- ‘George was the calming voice of reason’

Privately though, he was very open about what was happening. He thought about it all deeply too. Listening to him talk about it was both moving and inspiring. He seemed to take it all in his stride, with a calm dignity. He was not frightened.

“I answered a lot of the big questions eight years ago,” he told me recently. He found his way of coping, always positive, full of hope. At night, he had his checklist. “Will you be here tomorrow Georgie boy?” he’d ask himself. “Yes I will,” he’d answer and then go to sleep. He somehow managed to find a sort of peace – a place of contentment, as he later called it.

He told his team of brilliant doctors that they would have to do the worrying for him. He was going to spend the time he had living. What did upset him deeply though, was the thought of leaving his family behind.

Work helped him cope too. George loved being in the newsroom, surrounded by colleagues and friends. As the rounds of chemo mounted up, he began to find work physically exhausting. But mentally, he said it was rejuvenating, being with people who treated him as they had always done and who didn’t patronise him. He kept working for as long as he could, despite at least five major operations and more than a hundred rounds of chemotherapy.

I sat with him in hospital during his last round of chemo in May. He knew by then that he would not be coming back to work. But, after 20 years of presenting the BBC News at Six, George did want to say goodbye. Since being first diagnosed with cancer, just over nine years ago, he had received thousands of letters and messages from viewers who wrote to him as if they knew each other – strangers who treated him as a dear friend. It touched him deeply. And so he wanted to go on air one last time.

He had worked it all out. His plan was to do an interview with me at the end of the evening news and then turn to camera, on his own, with a simple goodbye. We could record something, I suggested. No. George wanted to do it live. I wasn’t entirely sure I would be able to hold it together. But if he could, I was going to have to as well.

In the end he didn’t get to do that. Shortly after that conversation he was back in hospital.

But despite the increasingly grim news from the medics, his spirit remained indomitable. Even towards the very end he was sending me texts, asking about my mother who was in hospital, also with bowel cancer. “How is your mum doing? You must be absolutely shattered. No pressure to answer until 100% convenient”, he wrote. I laughed out loud. It was so George. No mention at all of himself or his worsening health. He was always thinking about everyone else.

George died at the age of 67. The kindest, most thoughtful and generous soul. A man of great judgement and values. A great friend who taught me so much about living. I will miss him terribly.

Related Topics

- George Alagiah