Abstract

In the age of big data and open science, what processes are needed to follow open science protocols while upholding Indigenous Peoples’ rights? The Earth Data Relations Working Group (EDRWG), convened to address this question and envision a research landscape that acknowledges the legacy of extractive practices and embraces new norms across Earth science institutions and open science research. Using the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) as an example, the EDRWG recommends actions, applicable across all phases of the data lifecycle, that recognize the sovereign rights of Indigenous Peoples and support better research across all Earth Sciences.

Introduction

Earth Science is experiencing a data science revolution. Globally, more than 274 TB of Earth observation data are produced every day1. Amidst this data explosion, there is a global groundswell of Indigenous-led research on stewardship of lands, waters, and engagement with Indigenous Peoples2, bringing perspectives not typically present in Earth science research. While Indigenous Peoples have developed, maintained, and evolved knowledge systems via direct experience interacting with biophysical and ecological processes, landscapes, ecosystems, and species over millennia2, these Indigenous data (Box 1) often remain unrecognized or marginalized within contemporary discussions of environmental data. Broadly, Indigenous Peoples’ expertise has been excluded from settler-colonial and Western systems of scientific inquiry practices, land classification, and relations to the data about Indigenous homelands in digital environments3,4. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) reaffirms Indigenous Peoples’ collective rights to self-determination in the application of their political, economic, social, and cultural knowledge, but settler colonial (Box 1) institutions have largely failed to uphold these rights as they apply in digital environments and Earth science research.

NEON as an example to implement Indigenous data governance

The National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) is a National Science Foundation (NSF) facility managed by Battelle to collect continuous long term data to support research on drivers and responses to environmental change at continental scales5. NEON data are open and freely accessible with resources to support the development of big data skills in the research community, making climate change and ecological research potentially more available and inclusive6. To support high-quality, reproducible analyses, NEON, like most other large-scale Earth science projects, is committed to upholding FAIR Principles–making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable through data collection, documentation, and publication standards7,8. Some data repositories also engage the TRUST Principles- Transparency, Responsibility, User focus, Sustainability, and Technology- which focus on building and sustaining data infrastructures to meet the needs of user communities9. However, still missing in most large-scale Earth science projects, including NEON, are considerations for Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDSov) and Indigenous Data Governance (IDGov) (Box 1) in logistical and cyber infrastructure10. The NEON project provides a unique opportunity among the national scale research networks and data repositories to develop policies and practices within a large-scale settler-colonial science facility that acknowledges the erasure and exclusion of Indigenous relations in data infrastructures and seeks to operationalize the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance: Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, Ethics11. As an NSF-funded, continental-scale open science facility engaging in a broad range of data collection activities committed to equitable science, with partnerships across the Earth Science research community, NEON is a valuable case study to assess opportunities to implement CARE in a real-world Earth science network amidst complex research governance and funding structures.

Open science mandates and Indigenous data governance

In the US, federal agencies that fund research are increasingly mandated to enact open-access policies to make research products and data freely available and accessible to the public12. However, the mandates and their implementation don’t often consider the rights of Indigenous Peoples in relation to Earth observation data. Guidance for advancing open science while supporting IDGov exists in the complementary FAIR, CARE, and TRUST principles. While the FAIR principles advance technical guidance to optimize the reuse of data, TRUST guides repositories to serve users’ needs over time, and CARE brings a people and purpose orientation in alignment with Indigenous rights and interests7,9,13.

As Earth science researchers and institutions navigate open science environments, they can leverage FAIR, TRUST, and CARE to balance open science practices with responsibilities to uphold Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests in data. The US National Institutes of Health data management and sharing requirements provide a cooperative example that explicitly states that Tribal Nations’ laws, policies, protocols, and preferences must be upheld in the development and implementation of open data practices, data sharing agreements, and data management plans14. Likewise, the NSF has referenced and encouraged the implementation of FAIR and CARE across a variety of programs. NSF’s Office of Polar Programs Data, Code, and Sample Management Policy directs funded PI’s to align data management with FAIR and CARE Principles and provides explicit exceptions to the open data policy for Indigenous knowledge and data “where sensitivity, privacy, sovereignty, and/or intellectual property rights might take precedence”15. The Geosciences Open Science Ecosystem program lists the advancement of open science principles, including FAIR, CARE, and TRUST, as one of its priority goals16. CARE is also mentioned in NSF communications pertaining to the access of atmospheric science and data, and socially responsible development of climate mitigation strategies17,18. Moreover, NSF upholds standards of responsible and ethical conduct of research, including to “diligently protect proprietary information and intellectual property from inappropriate disclosure”19.

As Earth science researchers and institutions navigate open science environments, they must balance open science practices with responsibilities to uphold Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests in data.

There is a growing recognition of the value of including Indigenous knowledge systems in science and land management decision making20,21,22 and a growing body of literature to support conceptual frameworks11,23,24,25 but still few examples of what application looks like in an open science and repositories context. Here, we assess one specific project, to consider how the CARE Principles could be applied to inform how all institutes and projects across Earth Science can engage with Indigenous Peoples in ways that respect knowledge, acknowledge sovereignty, and enhance the quality of science possible by including more voices, perspectives, and priorities in research. Using the NEON facility as an example, this paper outlines opportunities for enhancing the governance of Indigenous data. Working with Indigenous and allied scholars in Earth sciences and the IDSov movement, we present recommendations that address each stage of the data and specimen life cycle that may be applied to research occurring across Earth system sciences.

The Earth Data Relations Working Group & research process

To explore NEON’s potential for implementing CARE, the Earth Data Relations Working Group (EDRWG) convened 18 members from November 2022 – August 2023 to develop recommendations for open data repositories and projects. Leveraging our boundary spanning -network partners, the group represented diverse perspectives across disciplines, geographies, and research efforts, comprising Indigenous individuals from more than 14 distinct Indigenous Peoples and eight regions within the United States and territories, as well as 6 non-Indigenous allies, including one international scholar from the Global North. Working group members represent diverse career stages, institution types (federal, academic, and research institutions, nonprofits), and disciplinary expertize (life science, social science, climate science, policy, data management, data science). Indigenous methodologies and perspectives were intentionally centered in all working group inquiries in recognition of the historic exclusion of these knowledge processes from Earth Sciences and the need to have Indigenous voices directing the practice of IDGov.

Specifically, the EDRWG took a Two-Eyed Seeing approach26, drawing on both Indigenous and Western worldviews. We also employed a participatory research approach to promote co-learning and reflection among collaborators. Beginning in November 2022, our working group convened monthly for facilitated meetings in which we shared definitions and applications of IDSov, IDGov, and the FAIR, CARE, and TRUST principles as they apply to each stage of the data and specimen lifecycle (design, infrastructure, collection, storage, reuse) in the NEON project and more broadly across Earth Systems Science research. Meetings were designed with the purpose of surfacing and exchanging each collaborator’s experiential knowledge in IDGov and the Earth Sciences, and facilitating individual and collective reflection about challenges and opportunities to further align research practices to the CARE Principles. By structuring space for continuous dialog across collaborators spanning disciplines, sectors, and fields, we identified a variety of IDGov strategies actively practiced across the entire data lifecycle and broader research ecosystem. This enabled us to co-create concrete recommendations for policy, practice, and infrastructure that scaffold all data actors’ shared responsibilities to IDSov. The recommendations proposed in this paper emerge directly from this inquiry.

This approach creates space for continuous exchange and reflection among interdisciplinary collaborators thinking about Indigenous Earth data. By sharing strategies mobilized in their own contexts, the Working Group identified best practices for stewarding Indigenous data of the past, present, and future.

Centering relationships

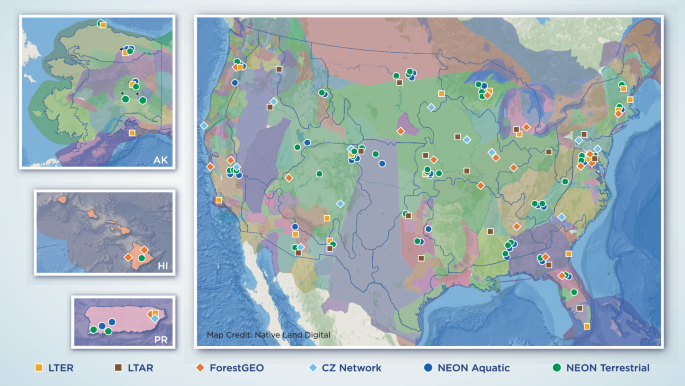

NEON has 81 field sites across the continental US, Alaska, Puerto Rico, and Hawai’i, each with direct relationships with land managers and local researchers. As a 30-year data collection project that produces over 180 data products, NEON is committed to maintaining positive engagement long term, at each site. Data are used globally, and data users come from many institutions, represent all career stages, and work with a variety of funding institutions. Wherever possible, NEON has adopted existing data collection standards and coordinates with existing Earth science communities and projects to ensure data are interoperable across networks. Because of the diverse data types and connections with other Earth science disciplines, NEON has become a hub in a network of networks, connecting many different Earth science data collection projects. In this space, NEON has the opportunity to share tools and advocate for data practices across many networks and data users in a way that enhances relationships between people, digital infrastructure, and data27 (Fig. 1).

Overlaying the major Earth Science network sites and NEON domains on a map of traditional and current Indigenous territories of North America from Native Lands Digital (native-land.ca) highlights the overlapping relationships with these locations. The main panel on the right depicts the contiguous United States, and the left panels depict (from top to bottom) Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico. Colored dots indicate the location of network sites, including Long Term Ecological Research (orange squares), Long Term Agricultural Research (red square), Forest Global Earth Observatory (orange diamond), Critical Zone Observatory (light blue diamond), NEON Aquatic (blue circle), and NEON Terrestrial (green circle) sites. NEON domains are outlined in black. Image credit Colin Wiliams and Rachel Swanson, NEON/Battelle.

Many Indigenous worldviews center relationships as a core value28. Relationships exist at the scale of the individual and collectives and apply to connections between humans, places, and biotic and abiotic communities in the past, present, and future. Likewise, relationships at multiple scales, from individuals to governmental agencies, are central to NEON as a scientific facility. These relationships exist along a spectrum across gradients of organizational complexity and responsiveness to change. On one side of the spectrum are direct relationships; each data user, project, and field site is connected to the NEON community. By implementing CARE in NEON’s data practices, enacting policies related to data use, and training data users, individual researchers will begin to modify their practices which in turn can guide a relationship-centered paradigmatic shift in federally-funded research. Those learned data behaviors initiate intergenerational patterns, staying with an individual as they progress through their career, appearing in projects and collaborations that those individuals contribute to on their journey.

On the other side of the spectrum is the increasing complexity of influencing change; on this side are multi-tiered institutions and funding agencies. While NEON and other large-scale Earth Science projects may not directly influence practices or guidelines from funding agencies, when the National Science Foundation (NSF), for example, supports projects that rely on NEON data, they will indirectly reinforce the implementation of the NEON policies around those data. Likewise, guidance that originates from funding agencies, like NSF (e.g., Office of Polar Programs Data, Code, and Sample Management Policy15), and governmental policies (e.g., Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Indigenous Knowledge22, Department of Interior Departmental Responsibilities for Consideration and Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in Departmental Action and Scientific Research29) reach individuals through practices implemented by NEON and other data networks and repositories. Each data actor, at any scale, holds the responsibility to honor IDSov and implement CARE. Doing so provides further support for intergenerational systemic change that better centers relationships with Indigenous Peoples (Fig. 2).

CARE may be implamented by data actors anywhere on the spectrum from individuals to multi-national bodies. Interactions across scales reinforce data governance practices to normalize data ethics within Earth System Sciences. Image credit Kathy Bogan, CIRES.

Four recommendations to advance Indigenous Data Governance

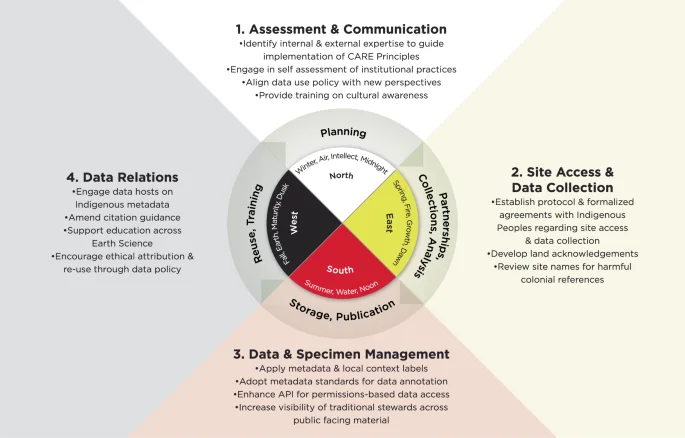

Applying this guidance to implement CARE in Earth science research can prove challenging on individual and institutional scales. It may not always be clear where to begin – or with whom responsibility lies – in incorporating IDGov into their policies and practices. Resources (e.g., funding, time, capacity, and training) are needed to orient researchers and institutions to their responsibilities to uphold IDSov and translate those responsibilities into actionable change and practice. Institutional support may be difficult to secure within academic institutions applying settler colonial values of ownership to data principles and policies. The EDRWG developed four recommendations as initial sites of action to implement the CARE Principles into all phases of the data lifecycle (Fig. 3). It was important to have a focused case study (NEON) to center the recommendations and make them actionable, but the recommendations are directed broadly across Earth science institutions and projects.

For many Indigenous Peoples of North America, the medicine wheel teaches about balance in contrasting aspects of the world and the nature of recurring cycles. The medicine wheel may, at times, represent the cardinal directions, natural elements, aspects of self, stages of life, seasons of the year, and times of the day (inner circle); here, we use it to think about the data and specimen life cycle (shaded outer circle) and the iterative nature of long-term research. We offer suggestions for bringing each aspect of an Earth Science project or institution into balance with sovereignty and multiple ways of knowing across settler colonial and Indigenous systems (bulleted text). Image credit Colin Wiliams, NEON/Battelle.

Adopt ongoing internal learning and assessment practices

Internal review of partnerships and practices is essential for effective and ethical engagement with Indigenous Peoples. For NEON, this includes understanding the direct and indirect impacts on Indigenous Peoples. In addition, cultural responsiveness training for all staff can address knowledge gaps and build foundational understanding regarding concepts of sovereignty, self-determination, and the ongoing impacts of settler colonialism.

For each Earth Science data repository, project, or institution, including NEON, this first step must also include assessment of their unique data lifecycles in order to identify appropriate internal and external expertize to guide implementation of CARE Principles and assessment of institutional practices.

While assessment and planning are an essential first step, internal governance and oversight for implementing CARE and applying IDGov cannot be treated as a one-off activity but instead, should be an iterative process intended to serve Indigenous Peoples and reflect community priorities within the institution. NEON relies on Technical Working Groups (TWGs)30, made up of external members to advise NEON on design and practices. We recommend establishing an Indigenous Data Governance TWG, composed of diverse Indigenous Peoples, to provide ongoing support in navigating decisions about IDGov within the observatory.

Develop collaborative access permission and research protocols

NEON sites are located on a variety of land designations, including public and private lands managed by US federal institutions, universities, non-profit, and private organizations. NEON holds land use permits with each of these land managers for the establishment of field sites and long term access to research plots. Consistent with the existing framework, we recommend NEON engage in a similar process of land and/or research permits with Indigenous Peoples and land stewards displaced by colonialism at each of the NEON locations as a means of establishing and documenting free, prior, and informed consent for the access, collection, and publication of data from sites. Across research networks, the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites are leading this effort, with some sites actively working on collaborative site access agreements, including the Central Arizona-Phoenix LTER and Konza Prairie Biological Station LTER [personal communication, Grimm and Zeglin]. The process of establishing formal agreements and regular iteration provides communities the opportunity to share protocols or expectations for field staff working on the land.

Currently, NEON operates three sites located on, or bordering, federally recognized Tribal lands, and 41 sites on public lands, (13 of which are located on lands administered by the Department of the Interior, subject to DOI policy to engage Indigenous Peoples in research activities29), and 37 sites managed by a mix of university, state, non-profit and private landowners. Future steps will need to consider each site more closely to identify Indigenous Peoples in relationship with these locations and develop engagement strategies appropriate for the overlapping responsibilities of diverse rights-holders and stakeholders.

NEON site names are based on geographic features or existing names for the site location and are not assigned by NEON. However, in some instances. these names may reflect harmful settler colonial histories and/or solely reflect settler colonial narratives while erasing Indigenous presence. Consistent with efforts to remove derogatory and harmful names from U.S. Federal Lands (DOI secretarial order 3405), working with site hosts and Indigenous Peoples to identify more appropriate names for the site demonstrates a commitment to end continued harm and recognizes Indigenous Knowledge held in traditional place names31. NEON should work to increase the visibility and respect of Indigenous stewards, past and present, in site descriptions and land acknowledgement. Where there is a paucity of information on Indigenous names for spaces, NEON, and other environmental data repositories can work with Indigenous rights-holders to better expand this knowledge.

In the course of specimen and data collection, NEON has encountered species not described in the scientific literature (for example, refs. 32,33). While changing the rules and norms for how new species are named is outside of the scope of any one project, researchers and taxonomists can support more equitable practices by engaging with Indigenous Peoples to collaboratively name species according to Indigenous methodologies and traditional knowledge protocols when the opportunity arises within the NEON project (ref. 34, and see for example, refs. 35,36,37). For example, species living within the Papahānaumokuakea Marine National Monument developed a naming process facilitated by the Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, community members, cultural practitioners, and researchers that honors the relationships created from engaging with the organisms and the ecosystems they inhabit38.

To recognize Indigenous Peoples rights, collaborative protocols, naming conventions, formalized agreements, and contractual obligations such as land use permits, Tribal research review processes, Memoranda of Understanding (MOU), Memoranda of Agreement (MOA), or research permits should be co-developed with Indigenous Peoples.

Enhance data and specimen management infrastructure

For data, specimens and samples that are part of a physical collection or digitally stored in a repository, it is essential that the metadata are linked with those records. Metadata describes the characteristics of a data set, such as structure, format, and context, as well as documentation associated with the digital collection record. Metadata provides information that informs data transformations and normalization but can also document required specimen handling procedures whenever the specimen/sample is accessed or used, establishing a complete provenance record39.

Removal of materials from the lands and waters of Indigenous communities is a physical separation from local knowledge systems. Thus, metadata is an important step to digitally re-connect species and samples to their Indigenous stewards. Such records should be co-developed and accessible to the Indigenous Peoples involved so that they can verify that the agreements made are actually being implemented. Moreover, if agreements reached with Indigenous Peoples include repatriation, i.e, the return to the site of the original collection, or rematriation, i.e., the reclamation and reassertion of spiritual relationships to Mother Earth, these need to be articulated in the procedures and timelines for carrying this out, as documented in data management plans (Box 1). In addition, specific measurements, procedures, and timelines for the return of cultural objects also need to be articulated.

Return of cultural objects has become institutionalized in federal and international legislation and policy as part of the recognition of human and cultural rights, as recognized by the United Nations Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as restitution for colonial harms40,41. Extension of these concepts to specimens and samples, which have kinship relationships with Indigenous Peoples, is an emerging dialog deserving of serious consideration. For example, discussion about the repatriation of Brazilian fossils from museums and private collections has garnered strong attention42 as well as legislation prohibiting non-human fossil removal from Native American lands43,44. Another example is how and where biological samples are stored. Samples and data could be stored by Indigenous partners, such as the Native Bio Data Consortium, whose biorepository facilities are housed on Indigenous lands by Indigenous researchers using Indigenous methodologies in Eagle Butte, South Dakota, USA. They store everything from genetic samples to interviews with Indigenous leaders and are an important example of an Indigenous-led repository.

Enhance data relations at all stages of the data lifecycle

A key component of enhancing data relations is developing formalized agreements with Indigenous Peoples around site access and data collection, as well as establishing community requirements around data obfuscation, data embargos, and data access restriction45. Within NEON, community requests and agreements around data management would be balanced by guidance from the NSF, as a sponsor of the NEON facility, to ensure compliance with the Data Management Plan and open science mandates. Moreover, as of May 2024, NSF is requiring Tribal Nation approval of proposals impacting Tribal resources and interests, demonstrating NSF’s commitment to advancing ethical and responsible research and investment in better understanding how to work with Indigenous communities and partners46. Implementation of agreements must be supported through appropriate metadata documentation47, application of needed Local Context Notices and Labels48, and communication around acceptable use of the data. Any limitations on data use and access restrictions should be generated and associated with the data record. This may include the use of community-vetted vocabularies (e.g., controlled term lists) or Indigenous languages as appropriate. Site-level metadata documenting data agreements and Indigenous Peoples’ relationships with NEON data should include information about who has authority and responsibility (e.g., village elder, government, Tribal Historic Preservation Office) to make data management decisions over time.

Cyber infrastructure enhancements may be necessary to support data embargo and security protocols in any application programming interface (API) technology, which allows different portals or applications to share data automatically. Access control mechanisms and their rationale need to be well described in all user-facing systems so that data users become familiar with the CARE Principles and their implementation. Furthermore, internal training on CARE for NEON staff that engages with the user community will reinforce CARE implementation and foster continued education through discussions with data users.

NEON’s data policies and citation guidelines outline NEON’s commitment to FAIR data principles, detail reuse permissions, and provide specific guidance for citing NEON data and documents8. These guidelines would be an appropriate place to document CARE within NEON data, to present statements recognizing that environmental data come from situated contexts with complex, living relationships between Indigenous Peoples and environmental data; and to provide resources for referencing the Indigenous land rights and stewards for the environmental data available on the NEON data portal. Specific metadata that references additional resources needed to understand the local environmental context should be highlighted in the data use policy. With permission from Indigenous Peoples whose lands or waters were the site of data collection, the portal could include a point of contact for additional dialog or discussion about data citation and use. While NEON can provide tools, infrastructure, and education around CARE Principles and the ethical use of data, it is important to note that NEON’s primary function is as a data provider. As such, NEON can recommend the appropriate use of data but cannot enforce how data downloaded from their publically available portal are applied.

Moving the CARE Principles from theory into action

As climate and biodiversity crises intensify, Earth Science institutions and researchers globally are racing to collect more data in an attempt to support research on drivers and responses to environmental change that can inform responses, risk communications, and adaptations. However, continuing this work from the same settler colonial framework that led to the current conditions will only perpetuate historical injustices and extractive practices. To transition from an extractive process to a relational and justice-centered one requires technology and systems grounded in the expertize held by Indigenous Peoples, who protect biodiversity, have experienced change, and pass down knowledge over generations based on direct observations49,50. This transition to more relational science practices is not only about more inclusive science, it is about upholding Indigenous Peoples’ sovereignty and self-determination, and adhering to the free, prior, and informed consent for engaging with data4. Updating observatory practices around site-based data and specimen collections is not aimed directly at broadening participation, rather, it is intended to uphold Indigenous Peoples’ sovereignty. Broadening participation and greater inclusion will naturally result from greater respect for Indigenous Peoples and individuals.

Like many large-scale Earth science projects, NEON operates within a web of relationships and contractual agreements. NEON’s scope and practices are directed by the NSF, and field site activities are negotiated and constrained by research or access permits with local land managers under many different land designations (e.g., NPS, USFS, BLM, and other Federal, State, University or Privately held lands). NEON cannot act independently to implement CARE, but has the opportunity to lead given its prominence among other such large-scale Earth science projects and institutions. NEON is well positioned to leverage existing partnerships to move from CARE, in theory, to CARE in action across national networks and federally funded research in the US. By demonstrating protocols that reinforce CARE Principles, such as those recommended here, NEON can foster enduring, positive change throughout the Earth science research community.

Implementing the above recommendations in NEON and broadly across Earth science institutions and repositories requires significant investment over time but will yield major improvements to research infrastructure that recognize sovereign rights of Indigenous Peoples and transition science practices in the US from an extractive-based process to a relational one. NEON, as an observatory for ecology that explores the relationships between organisms and their environment, is tuned to hold the importance of relationships at many scales. Though not initially designed with consideration for Indigenous Knowledge, rights, data systems, and land relations, NEON and other Earth science institutions and repositories now have an opportunity to respond to the changing norms for including Indigenous perspectives by establishing logistical practices and cyber infrastructure that recognize IDSov and enact IDGov.

For NEON, we recommend prioritizing implementing CARE Principles at NEON sites on Tribal lands, the Department of Interior managed sites based on pre-existing guidance, and work with co-located network research sites as part of the coordinated effort to engage Indigenous partners across Earth sciences. Scientific institutions play a key role in communicating the priorities of the research community to funding and land management agencies, so investment in CARE Principles and applications demonstrates a commitment to equitable research practices.

The EDRWG recommendations form the basis for major infrastructure and institutional policy and practice changes that will require substantial resources and long-term investment. Funders such as NSF can further uphold sovereign obligations by requiring CARE in data management plans and allocating funding for implementation. Re-situating the fundamental importance of upholding sovereignty in scientific research and institutions will take a concerted effort across all levels of complexity, accessibility, and intergenerational influence.

Here we focus our evaluations on NEON for the purpose of developing and grounding recommendations for implementation of IDGov in a specific example of an open science project. To be sustained, these recommendations need to be broadly implemented in open science research and repositories across Earth Sciences globally. Implementing Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics in open science means addressing practices in every stage of the research and data lifecycle. The Earth Data Relations working group identified four actions that include the need to develop infrastructure, policies, and practices that embed CARE, to ensure that IDSov and IDGov are at the forefront of environmental scholarship. Moving away from the framework of settler colonial methodologies that separate people from ecosystems toward a relational framework that recognizes our interdependencies on ecosystems will result in better science, science that is more diverse, more ethical, and respects the knowledge and relationships that Indigenous data stewards have built with environmental data.

References

-

Wilkinson, R. et al. Environmental impacts of earth observation data in the constellation and cloud computing era. Sci. Total Environ. 909, 168584 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Atleo, U. / E. R. Principles of Tsawalk: An Indigenous Approach to Global Crisis. (University of British Columbia Press, 2012).

-

Whyte, K. Settler colonialism. Ecol. Environ. Injustice. Environ. Soc. 9, 125–144 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Whyte, K. et al. in Fifth National Climate Assessment (U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 2023).

-

Keller, M., Schimel, D. S., Hargrove, W. W. & Hoffman, F. M. A continental strategy for the National Ecological Observatory Network. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 282–284 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Nagy, R. C. et al. Harnessing the NEON data revolution to advance open environmental science with a diverse and data-capable community. Ecosphere 12, e03833 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

NEON. Data Policies & Citation Guidelines. NSF NEON | Open Data to Understand our Ecosystems https://www.neonscience.org/data-samples/data-policies-citation (2021).

-

Lin, D. et al. The TRUST Principles for digital repositories. Sci. Data 7, 144 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Jennings, L. et al. Applying the ‘CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance’ to ecology and biodiversity research. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1547–1551 (2023).

-

Carroll, S. R. et al. The CARE Principles for Indigenous data governance. Data Sci. J. 19, 43 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Ensuring Free, Immediate, and Equitable Access to Federally Funded Research. https://doi.org/10.5479/10088/113528 (2022).

-

Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K. & Stall, S. Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR principles for Indigenous data futures. Sci. Data 8, 108 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

National Institutes of Health. Final NIH Policy for Data Management and Sharing. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-21-013.html (2020).

-

U.S. National Science Foundation. Dear Colleague Letter: Office of Polar Programs Data, Code, and Sample Management Policy (nsf22106). (2022).

-

U.S. National Science Foundation. Geosciences Open Science Ecosystem (GEO OSE). https://new.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/geosciences-open-science-ecosystem-geo-ose (2022).

-

U.S. National Science Foundation. Supporting Use of Existing Data and Samples in Atmospheric Sciences Research and Education. https://new.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/supporting-use-existing-data-samples-atmospheric (2021).

-

U.S. National Science Foundation. CO2 Removal and Solar Radiation Modification Strategies: Science, Governance and Consequences. https://new.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/co2-removal-solar-radiation-modification (2023).

-

U.S. National Science Foundation, Office of the Director. Responsible and Ethical Conduct of Research (RECR) | NSF – National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/od/recr.jsp.

-

Kimmerer, R. W. & Artelle, K. A. Time to support Indigenous science. Science 383, 243–243 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Souther, S., Colombo, S. & Lyndon, N. N. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge into US public land management: Knowledge gaps and research priorities. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.988126 (2023).

-

White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Memorandum to the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies, Guidance for Federal Departments on Agencies on Indigenous Knowledge. (2022).

-

UN General Assembly. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Resolution / Adopted by the General Assembly. U.N. GAOR (2007).

-

Garba, I. et al. Indigenous Peoples and research: self-determination in research governance. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 8, 1272318 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Reid, A. J. et al. Ecological research ‘in a good way’ means ethical and equitable relationships with Indigenous Peoples and Lands. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 595–598 (2024).

-

Peltier, C. An application of two-eyed seeing: Indigenous research methods with participatory action research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 17, 1609406918812346 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

SanClements, M. D. et al. People, infrastructure, and data: A pathway to an inclusive and diverse ecological network of networks. Ecosphere 13, e4262 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Montgomery, M. & Blanchard, P. Testing justice: New ways to address environmental inequalities. Solut. J. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2022-02-17/testing-justice-new-ways-to-address-environmental-inequalities/ (2021).

-

Department of the Interior Office of Policy Analysis. 301 DM 7 Departmental Responsibilities for Consideration and Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in Departmental Actions and Scientific Research. (2023).

-

NEON. Technical Working Groups. NSF NEON | Open Data to Understand our Ecosystems https://www.neonscience.org/about/advisory-groups/twgs.

-

McGill, B. M. et al. Words are monuments: Patterns in US national park place names perpetuate settler colonial mythologies including white supremacy. People Nat. 4, 683–700 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Ciugulea, I. et al. Adlafia neoniana (Naviculaceae), a new diatom species from forest streams in Puerto Rico. Plant Ecol. Evol. 152, 378–384 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Will, K. & Liebherr, J. K. Two new species of Mecyclothorax Sharp 1903 (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Moriomorphini) from the Island of Hawai‵i. Pan Pac. Entomol. 98, 1–17 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Gillman, L. N. & Wright, S. D. Restoring indigenous names in taxonomy. Commun. Biol. 3, 1–3 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Wright, S. D. & Gillman, L. N. Replacing current nomenclature with pre-existing indigenous names in algae, fungi and plants. TAXON 71, 6–10 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Nielsen, S. V., Bauer, A. M., Jackman, T. R., Hitchmough, R. A. & Daugherty, C. H. New Zealand geckos (Diplodactylidae): Cryptic diversity in a post-Gondwanan lineage with trans-Tasman affinities. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 59, 1–22 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Spalding, H. L., Conklin, K. Y., Smith, C. M., O’Kelly, C. J. & Sherwood, A. R. New Ulvaceae (Ulvophyceae, Chlorophyta) from mesophotic ecosystems across the Hawaiian Archipelago. J. Phycol. 52, 40–53 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

National Ocean Service, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, & National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Papahānaumokuākea: A Sacred Name, A Sacred Place. Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/about/name.html (2022).

-

Cheney, J., Finkelstein, A., Ludäscher, B. & Vansummeren, S. Principles of Provenance (Dagstuhl Seminar 12091). vol. 2 (2012).

-

Breske, A. Politics of repatriation: Formalizing indigenous repatriation policy. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 25, 347–373 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Carpenter, K. A. A human rights approach to cultural property: Repatriating the Yaqui Maaso Kova. Cardozo Arts Ent. L. J. 41, 159 (2022).

-

Cisneros, J. C., Ghilardi, A. M., Raja, N. B. & Stewens, P. P. The moral and legal imperative to return illegally exported fossils. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 2–3 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Dalton, R. Laws under review for fossils on native land. Nature 449, 952–954 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Stewens, P. P., Raja, N. B. & Dunne, E. M. The return of fossils removed under colonial rule. Santander Art. Cult. L. Rev. 2022, 89 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

O’brien, M. et al. Earth science data repositories: Implementing the CARE principles. Data Sci. J. 23, 37 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

U.S. National Science Foundation. Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (NSF 24-1). (2024).

-

IEEE. Recommended Practice for Provenance of Indigenous Peoples’ Data. (2020).

-

Local Contexts – Grounding Indigenous Rights. https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/2890/10318/.

-

Lazrus, H. et al. Culture change to address climate change: Collaborations with Indigenous and Earth sciences for more just, equitable, and sustainable responses to our climate crisis. PLOS Clim. 1, e0000005 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Wildcat, D. Red Alert!: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge. (Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, CO, 2009).

-

Global Indigenous Data Alliance, Carroll, S. R., Cummins, J. & Martinez, A. Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance. (2022).

-

Rainie, S. C. et al. in State of Open Data: Histories and Horizons (eds. Davies, T., Walker, S. B., Rubinstein, M. & Perini, F.) (African Minds, Cape Town, 2019).

-

Carroll, S. R., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. & Martinez, A. Indigenous data governance: Strategies from United States native nations. CODATA 18, 31 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Tuck, E. Rematriating curriculum studies. J. Curric. Pedagog. 8, 34–37 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Hird, C., David-Chavez, D. M., Gion, S. S. & Van Uitregt, V. Moving beyond ontological (worldview) supremacy: Indigenous insights and a recovery guide for settler-colonial scientists. J. Exp. Biol. 226, jeb245302 (2023).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We remember Heather Lazrus and acknowledge that her leadership was instrumental in bringing the Earth Data Relations Working Group together. We gratefully acknowledge Kirsten Ruiz, Christine Laney, Kelsey Yule, and Nico Franz for sharing expertize on the NEON use case and Darren Ranco for contributions to the working group. Lastly, we thank Indigenous land stewards and knowledge keepers of the past, present, and future. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2220614. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: K.J., L.L.J., S.R.C., J.M., and H.L. Funding Acquisition: K.J., L.L.J., S.R.C., J.M., and H.L. Methodology: L.L.J., K.J., S.R.C., and J.M. Investigation-working group participation: K.S., D.R., K.R., C.L., N.F., K.Y., L.L.J., K.J., R.T., A.M., D.D.C., R.A.A., A.T.N., J.M., B.T., D.D., J.W., K.V.S., S.K., R.D., N.J., J.B., and S.R.C. Project administration: K.J. and A.M. Validation: R.D., J.B., J.W., D.D.C., R.A.A., B.T., and S.R.C. Visualization: K.B., K.J., C.W., and R.S. Writing Original Draft: K.J., L.L.J., R.T., A.M., J.M., J.W., R.A.A., R.D., D.D.C., A.T.N., B.T., S.K. and S.R.C. Writing, reviewing, and editing: K.J., L.L.J., R.T., A.M., D.D., J.M., R.A.A., J.B., R.D., and D.D.C.

Author positionality statement

LLJ is a citizen of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe (Yoeme), Huichol (Wixarika), and Greek woman raised in Tewa lands. Her work centers soil health, environmental data stewardship and science policy. KJ is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Nation (Amskapi Piikani), and of mixed European descent. As a staff scientist on the NEON project and a program lead for the Rising Voices Center for Indigenous and Earth Sciences, her focus is on supporting research in the areas of plant ecology and phenology while uplifting research practices that honor both Indigenous and Western approaches to understand and respond to climate change. RT is a Chamoru (Indigenous peoples of the Mariana Islands) woman with ties to the island of Guåhan/Guam. She is also of mixed European descent and lives in San Diego on Kumeyaay lands. Her work seeks to advance Indigenous self-determination over data and environmental decision-making processes. AM is a citizen of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. He is also Yaqui and Diegueno/lipay with family from the Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians in San Diego County, California. He serves as the Research Coordinator with the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance. DDC is multicultural Indigenous Caribbean (Arawak Taíno), carrying Indigenous Boricua, African, Spanish, and East European ancestry. She directs the Indigenous Land & Data Stewards Lab on Indigenous homelands, including those of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Ute Nations in the Colorado Front Range. RAAʻs centers a critical ʻōiwi (Native Hawaiian) perspective on research as praxis, training scholars to draw upon multiple knowledge systems to address key problems and empower communities to understand and protect their resources. Her work applies contemporary and ʻōiwi methodologies to understand eco-evolutionary processes influencing the microbiomes of Indigenous seascapes. She is an advocate for Indigenous data sovereignty and co-development of processes for building and sustaining equitable relationships between researchers and communities. ATN is a French-Iranian third-culture individual currently based in Spain. He’s a research technician at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and also works for various NGOs as a freelance climate and environmental justice researcher. JM is of Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Spanish, and Turkish descent, living in California’s central coast, the traditional homelands of the Coastal Chumash Nation. Driven to connect with those committed to service, collaboration, and community-centered climate action, she co-founded the Livelihoods Knowl LiKEN, a non-profit link-tank that grows through infrastructures of care. In this capacity, Julie serves as co-director of the Rising Voices Center for Indigenous and Earth Sciences. BT helped to establish the Pacific Risk Management ‘Ohana, or PRiMO in 2003 to collectively address linkages between climate change, environmental degradation and social injustice. Over the past 20 plus years, it has expanded to include Alaska, the continental US and the Caribbean. PRiMO’s foundation is based on the generations of knowledges and experiences in protecting and restoring our islands’ natural resources, cultures, histories and our futures passed on to us by our kupuna (ancestors). A marine biologist born and raised in Hawai’i, Bill is of Native Hawaiian, Maori, Chinese, Scottish, Irish, Welsh and Scandinavian descent. DD, a New Mexico resident, earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in Geography. As an educator and research scientist at a national Tribal College, he is engaged in developing and sharing practical approaches to support effective IDSov and IDGov. He is an enrolled member of Cherokee Nation and has mixed Cherokee and European ancestral descent. JW is U.S. born, western educated, white, Arctic climatologist with decades of DEI engagement experience. KVS is a lifelong Alaskan of Italian and Irish descent who was born and raised and is raising her family on the lands of the Lower Tanana Dene in Fairbanks, Alaska. She is a plant ecologist, learning researcher, and teacher working in cross-cultural climate change research and teaching spaces in Alaska. SK is an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation and has a mixed European, Choctaw, Cherokee, and Lenape ancestry. He is the Chickasaw Nation Endowed Chair in Native American Studies at East Central University in Ada, Oklahoma. RED is a non-Indigenous researcher/data manager with a wide range of international experience including Indigenous data management with the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic, membership on the Arctic Data Committee, and leadership roles in both ESIP and the Research Data Alliance. NJ is of Norwegian and unknown mixed European descent. She lives in Cambridge, MA, on the traditional and ancestral land of the Massachusett. Trained as a cultural anthropologist, she works as a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center where she leads the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA), a program that supports stewardship of Arctic Indigenous data. JKB is of mixed European descent living and working in Boulder, CO on the traditional homelands of the Tsistsistas (Cheyenne), Hinono’eino’ (Arapaho), Nunt’zi (Ute), and many other Tribal Nations. She is a fire ecologist who aims to understand the holistic processes that underlie disturbance, ecosystem recovery, and societal resilience. Her work at ESIIL aims to empower others to leverage open, ethical environmental data science at a time when society needs all perspectives, and science needs to serve all. SRC is an Ahtna woman, a citizen of the Native Village of Kluti-Kaah along the Copper River in Alaska, and of Sicilian descent. She directs the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance, a research network that seeks to transform institutional governance and ethics for Indigenous control of Indigenous data, particularly within open science, open data, and big data contexts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Emilie Ens and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jennings, L., Jones, K., Taitingfong, R. et al. Governance of Indigenous data in open earth systems science.

Nat Commun 16, 572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53480-2

-

Received: 29 March 2024

-

Accepted: 14 October 2024

-

Published: 10 January 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53480-2