The Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station is starting research on using microwave frequencies to inactivate weed seeds and increase the efficacy of herbicides.

Nilda Burgos, professor of weed physiology and molecular biology at the University of Arkansas, the principal investigator of the study, said if the research can show a reduction in the seed bank by only 50%, it would greatly increase the efficacy of herbicides and reduce herbicide use.

“It will be another tool for integrated weed management that is sustainable and non-chemical,” she said.

The study is being supported by $300,000 from an Agriculture and Food Research Initiative grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, with additional support from The Cotton Board and Cotton Incorporated.

Studies have previously shown that burning is effective at destroying weed seeds, but the resulting smoke causes problems with air quality and road visibility. Weed seed crushers are also effective, however they do not do anything for seeds that have already been dropped or buried in the soil.

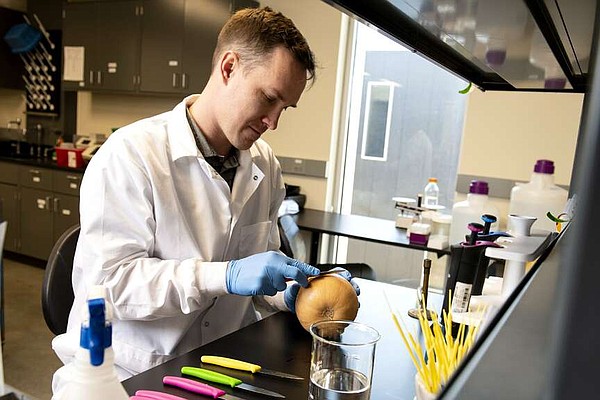

Preliminary research that has shown the 915 MHz frequency microwaves control weedy rice was done by Kaushik Luthra, a food science postdoctoral fellow with the University of Arkansas, and Griffiths Atungulu, associate professor and agricultural engineer for grain processing at the University of Arkansas, according to a University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture news release.

In-home microwaves have high frequency waves, whereas the waves used in the study are low frequency and are able to interact with the water molecules inside and on the surface of the weed seeds. Researchers are using the lower frequencies to penetrate below the soil surface to reach the weed seeds.

“The water molecules constantly try to align with the change in polarity of the microwaves, creating resistance and heat,” Luthra said. “The temperature rises, and the embryo of the seed is destroyed.”

While the new study focuses on weeds common in cotton fields, the ten weeds in the study are also common in other major commodity crops.

One of the weeds tested in the study will be Amaranthus palmeri, or Palmer pigweed, which can lead to yield losses up to 91% in corn and 79% in soybeans by out competing the crop, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Burgos added herbicide-resistant weeds are the most problematic and expensive management issue in row-crop agriculture.

Fields infested with nutrient stealing weeds can become unproductive because the weeds cannot be controlled by herbicides.

Burgos said synthetic chemical herbicides are popular because they are effective against a broad spectrum of weeds and are more effective than natural herbicides. However, the chemicals target just one enzyme to disrupt the weed’s ability to function.

“In most cases, weed populations become resistant to herbicides due to selection of plants with a mutation in the herbicide target that prevents interaction with the herbicide,” she said.

While possible to mutate, Burgos said the mutation is extremely rare, but the possibility of selecting them increases with the number of plants exposed and frequency of herbicide use.

The study examining the microwaves will last two years and evaluate the effect of a plant-growth regulator to assist herbicide activity on reducing weed fertility and seed germination.

This study is not the first to evaluate the effects of microwave frequencies in agriculture, with The Rice Processing Program developing microwave technology for high-throughput rice drying.