Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Polish collector, entrepreneur and philanthropist Grażyna Kulczyk — born in 1950 — is among the country’s wealthiest women. She has homes in Warsaw and London, but mainly lives in the pretty village of Susch in the Lower Engadine Valley in Switzerland. There she opened the private Muzeum Susch in 2019, showing contemporary art.

The beguiling museum is sited in a complex of four buildings, including a 12th-century monastery and a 19th-century brewery. It boasts dramatic cavernous spaces that were blasted out of the mountain, some of which hold site-specific works by Polish artists such as Monika Sosnowska, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Piotr Uklański, Mirosław Bałka as well as others by Helen Chadwick, Tracey Emin and Not Vital.

Sitting in the museum office, Kulczyk is tiny, passionate and forthcoming, her blonde hair tied back leaving a thick fringe at the front. She has long supported women artists, was among the first members of Tate’s Russia & Eastern Europe Acquisitions Committee and is currently on the board of Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art. Last year at Davos she received the World Woman Hero in Art & Philanthropy Award.

It all started with a moment of intuition. I was running a car dealership after leaving university, and began inviting young Polish artists to present their work in the showroom alongside modern western cars that, after years of shortages under the socialist economy, sparked dreams and excitement in Poles. At the time, I wasn’t thinking about building a collection. I was simply reacting emotionally to art. Supporting and collecting Polish art felt natural to me. Over time, I became more confident in reaching for international artists. And believe me, for someone who had lived behind the Iron Curtain for decades, that required a profound shift in perspective. While I don’t remember the first work I bought then, I do remember buying my first work at Sotheby’s — it was 25 years ago, and was “Efecto de bastón en relieve” (1979) by Antoni Tàpies, a very minimalistic work showing a walking stick encased in canvas. It was my first acquisition there, and the first day for the person I bought through; it was the start of a long friendship!

I smile every day at “The Bride” by Jenny Saville in my house in the Alps. It dates from 1992, when she was still in her fourth year at Glasgow School of Art. It represents for me the defiant, feminine voice of the 1990s — the very essence of Young British Artists’ energy.

The piece I dream of owning is a work by Domenico Gnoli. His paintings contain so many subtle, feminine accents — precise, mysterious, tender. In the close-ups of hair, fabric or fragments of the body, there’s something deeply intimate, as if he were exploring femininity without ever showing the full figure.

There was a painting I hesitated over many years ago at an art fair. A quiet, refined early work by Robert Mangold; I don’t remember its title today. At that time, I was collecting many minimalist artists. I thought I had time, but I didn’t! Since then, I’ve made peace with the fact that we do not have to possess everything that moves us.

Muzeum Susch came about because I wanted to create a space for reflection, for research, for rethinking the canon and rewriting art history — by restoring a voice to forgotten or misread women artists of the avant-garde (such as Laura Grisi, Feliza Bursztyn and Anu Põder), and deepening reflection on the meaning of female creativity in culture. And I plan, in the next two years, to publish an anthology about the women artists who were missed or even forbidden in many countries, especially from eastern Europe.

For me, collecting art, especially by women, is a way of telling stories. Not one story, not a linear story, but many parallel ones — often contradictory, often silenced. What has changed, unfortunately, is the commodification of collecting. But I still believe in art’s power to transform, not just to decorate.

Our new space is the last missing piece of the monastery complex, a building that housed the Hospiz San Jon which I have finally been able to buy. I am converting it to show my own collection, which numbers some 600 works. I hope to open it in 2026 or 2027. It’s very important finally to have a place in which to show what I collect, as it makes no sense to have it in a warehouse. And I can’t stop buying art — it’s like a drug.

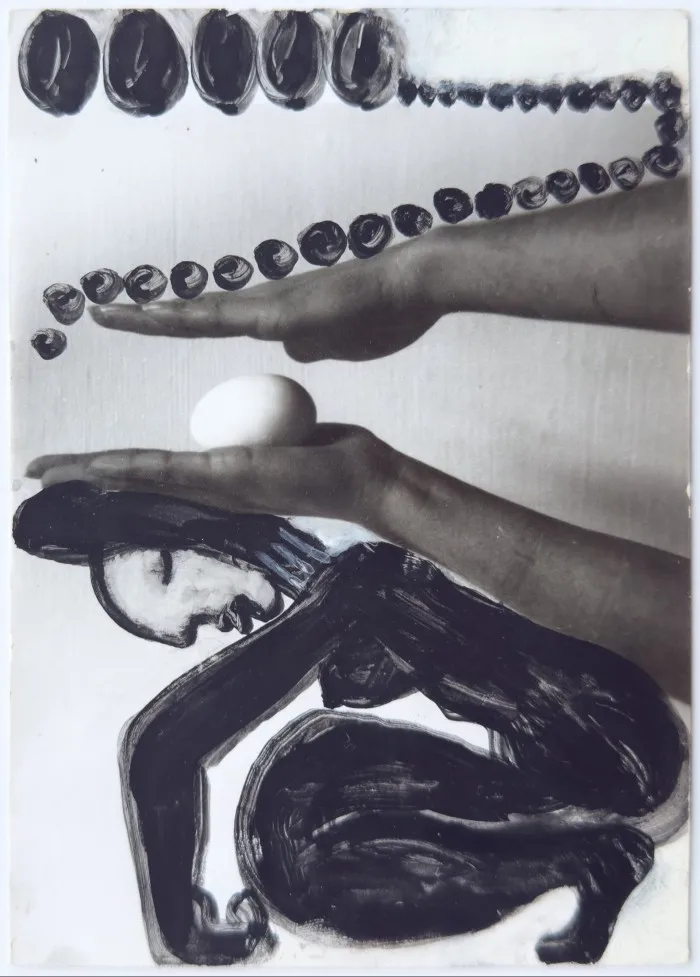

On June 15 we are opening two parallel exhibitions of artists particularly close to my heart: Gabriele Stötzer and Jadwiga Maziarska. Both feature works on loan from my private collection. I have a dedicated room for photography by women — I will show Gabriele’s work there. A landmark survey of Maziarska, with more than 100 works spanning the 1940s to the 1980s, will be the artist’s first institutional retrospective outside Poland.

muzeumsusch.ch

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning