RICHMOND — Virginia is home to the largest data center market in the world, but citizens and lawmakers have urged leaders to temper the onslaught of development and consider the impact.

Data centers have brought hundreds of millions in tax revenue and thousands of jobs to Northern Virginia, and increasingly, other areas of the state. But among environmental groups, there is mounting concern that the rapid growth of the industry might offset climate goals laid out in past legislation.

Data centers are physical locations that power online activity “in the cloud,” according to the Data Center Coalition. The centers support online activities that individuals, governments, organizations and businesses of all sizes do every day, according to the group’s president, Josh Levi.

The growth of the industry shows no signs of slowing. Gov. Glenn Youngkin announced a deal with Amazon Web Services in January to establish multiple data center campuses across the state. The company plans to invest $35 billion in Virginia by 2040.

Amazon Web Services filed in September to develop two campuses in Louisa County, including a seven-building data center campus, Lake Anna Technology Campus. The campus would occupy almost 2 million square feet of Lousia County’s land, including about an acre of wetland.

“These areas offer robust utility infrastructure, lower costs, great livability, and highly educated workforces and will benefit from the associated economic development and increased tax base, assisting the schools and providing services to the community,” Youngkin stated about the partnership with Amazon Web Services.

The state also developed a new incentive program to help clinch the deal. An amount not to exceed $140 million in grant money will go toward the company and end no later than 2044, according to the recently passed budget. The grants help with infrastructure improvements, workforce development and other project-related costs. The grant awards $8,642 for each new full-time job and $3,364 for each $1 million of capital investment made the year before.

___

Money and jobs

The two primary benefits of data centers are local revenue and job creation, according to Levi.

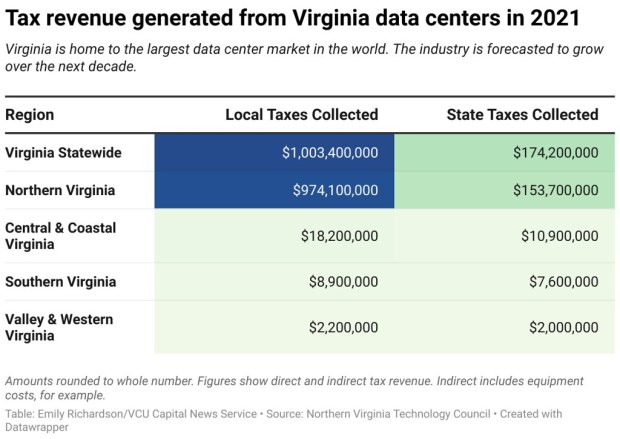

A report by the Northern Virginia Technology Council found that data centers provided approximately 5,500 operational and over 10,000 construction and manufacturing jobs in 2021. The report estimated that data centers were “directly and indirectly” responsible for generating $174 million in state tax revenue and just over $1 billion in local tax revenue around the state.

Every data center proposal in Virginia to date has been approved, according to Wyatt Gordon, senior policy and campaigns manager of land use and transportation with the Virginia Conservation Network.

The high concentration of data centers in the state is a significant problem, according to Gordon.

“If this is going to support global internet traffic, they need to be across the globe instead of just within one region of one state,” Gordon said.

There is no future without data use, Gordon said, but the impacts of data centers need to be studied closely.

“I think our immediate concern is just, how are we making sure that the impacts of these data centers as they’re coming here are really being negotiated in a way that makes sense for Virginia,” Gordon said.

Del. Danica Roem, D-Manassas, and Sen. J. Chapman Petersen, D-Fairfax, worked with the Virginia Conservation Network on a bill this past session to have the Department of Energy study the impacts of data center development on Virginia’s environment and climate goals. The bill failed.

The legislators attempted to pass other bills with measures to regulate where the centers could be built and to employ conditional stormwater runoff management.

“It’s the biggest corporations in the entire world on one side, and then you have Virginia residents and a ragtag group of environmental folks on the other,” Gordon said. “So, I think you know who won.”

___

Environmental concerns

There are three primary impacts of data centers on the environment, according to Gordon: the space they take up, the groundwater demand for cooling and their energy use.

The facilities set to come out of Youngkin’s Amazon deal, alone, will be the size of 151 Walmart stores, according to Gordon.

“That is massive amounts of land that are currently forests, farmland, wetlands, and are going to be bulldozed and converted into gigantic boxes hosting servers,” Gordon said.

Overall, energy use in Virginia has gone down due to increased energy efficiency, according to Gordon. But data centers are a growing sector of electricity demand in Virginia, according to a report prepared for the Virginia Department of Energy.

Data center electric sales will increase 152% in the next decade, while other sectors will remain mostly the same, according to the Energy Transition Initiative. The forecast does not include projected electricity demand from electric vehicles.

The overall increase in Virginia electricity sales is forecasted to be 32% over 10 years, and accounts for increased energy efficiency.

Dominion Energy filed an Integrated Resource Plan this year that anticipates a higher demand for electricity from data centers than originally planned. Recently, Dominion filed permits for natural gas and coal power plants to meet data center energy demands, according to Gordon.

This contrasts the Virginia Clean Economy Act, according to Gordon, which mandates the state’s two largest utility providers, Dominion Energy and American Electric Power, produce 100% renewable electricity by 2045 and 2050 respectively.

“Despite being the only Southern state to pass such a huge climate law … that could all collapse because data centers are putting such a demand for power that there’s no way to supply them in a timely manner without relying upon dirty energy,” Gordon said.

At present, Dominion Energy is “writing checks that Virginians can’t cash,” according to Julie Bolthouse, director of land use at the Piedmont Environmental Council. The group has looked at data center development in its service region since 2017.

Virginia is compromising its conservation and climate goals to meet in-service dates, with costs of development falling on utility ratepayers, according to Bolthouse.

“We have to, now, meet that in-service date that they committed to and we have to build out this infrastructure with a rate schedule that’s unfair to us because we’re sitting here paying for all of this when it’s benefitting this one industry,” Bolthouse said.

A Dominion Energy representative did not respond to a request for comment by time of publication.

The utility and data centers negotiate electricity contracts together, then determine an in-service date when the utility will begin providing power, according to Bolthouse.

“The industry needs to wait for us to be able to provide that power in a sustainable manner,” Bolthouse said.

Powering Virginia’s data centers with renewable energy is a realistic goal “over time,” according to Levi. Amazon Web Services, for example, states that it plans to fund 18 solar farms in Virginia that would provide enough energy to power 276,000 homes by 2025.

Though there are many ways companies can pursue clean energy, the challenge is how fast they can provide it, Levi said.

“I think that’s where some of the hand wringing around this issue is really coming from,” Levi said.

___

Looking forward

Prince William Digital Gateway is the “epitome” of everything the data center industry is doing wrong, according to Kyle Hart, the mid-Atlantic program manager at the National Parks Conservation Association.

“We wouldn’t be where we are today, in terms of broad calls for industry-wide reform, if this terrible proposal hadn’t existed and had never sort of marched forward under a Democratic board majority for the past two years,” Hart said.

The group became involved in the conversation because of data center projects like Prince William Digital Gateway, which would share a border with Manassas National Battlefield Park, according to Hart.

Most recently, the Prince William County Planning Commission voted to recommend denial of all three rezoning applications involved in the Digital Gateway project. The debate moves next to the board of supervisors for a vote.

Hart and Bolthouse offered policy suggestions in a paper that provides an overview of data center development from a land use perspective. They suggested a study on the various impacts of development, a grid impact statement by the State Corporation Commission for all new data center-related power demand requests, and a framework for a regional review board to evaluate these large project proposals.

The data center proliferation in Virginia has outpaced any other state, which ultimately left Hart and Bolthouse without much framework to work off, Hart said. The suggestions are based on what they would want to see.

Elena Schlossberg is executive director for the Coalition to Protect Prince William County, a grassroots effort at the forefront of the resistance against the Digital Gateway. Schlossberg encouraged people to educate themselves on why they should care about the issue.

“You can make a difference by telling your neighbors,” Schlossberg said. “You can make a difference by getting on a bus and lobbying your state legislators that there needs to be some real oversight for an industry that is, up until this point, pretty unregulated.”

The data center debate is apolitical, according to Schlossberg.

“Money knows no ideological boundary, nor does doing the right thing,” Schlossberg said.

Capital News Service is a program of Virginia Commonwealth University’s Robertson School of Media and Culture. Students in the program provide state government coverage for a variety of media outlets in Virginia.