Imagine a woman in her forties, the mother of two children, sitting at a kitchen table in the Bronx, obsessively exorcising her terrors by piecing together scraps of fabric, torn paper and string into elegant collages for nobody to see.

Hannelore Baron, an artist so overcome by anxiety and mental anguish that she rarely left the house, shut out 20th-century America where protests raged, cultures clashed and bloodshed dragged on in Vietnam. And yet, even hunkered in her lair, she somehow osmosed cutting-edge aesthetics and an ample aggregate of influences. Her work harmonised an unsettled psyche with that roiling time.

She made art as a quiet scream of protest — “the way other people marched to Washington, or set themselves on fire, or write protest letters, or go to assassinate someone”, she explained to her son, with a mixture of outrage and resignation. “And it probably will have the same effect, which means nothing at all.”

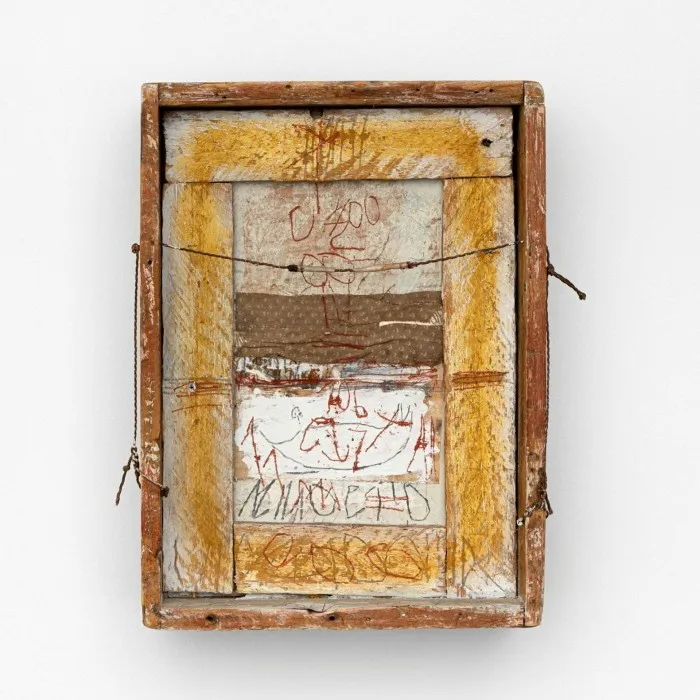

Baron made these intimate collages for her own satisfaction, and they have not circulated widely in the decades since she died in 1987. Finally, though, a major crop — 56 pieces in all — has surfaced at Michael Rosenfeld gallery in New York, offering a rare encounter with a refined, heartfelt and powerful body of work. Small, dense and simmering rather than explosive, these boxes and collages ask viewers for some of the methodical patience that fuelled her labour. They reward careful study and frustrate the quick glance.

Born into a Jewish family in Germany in 1926, Baron saw her father forced to close his fabric shop and knock on doors to sell his wares instead. She was 12 on Kristallnacht, when a mob ransacked the family home and beat her father so brutally that he left a bloody handprint on the living room wall, an image that remained with her always. He was arrested and sent to Dachau, then miraculously released. The family eventually managed to escape, arriving in New York in 1941.

A stint on the sales floor of a Manhattan department store made plain the lasting damage of those years; she began to suffer severe bouts of claustrophobia. Her uncle, a doctor, prescribed sedatives and advised her to keep her mental illness strictly under wraps. The assemblages beg to be viewed as confidences yearning to break out. At once gridded and chaotic, by turns clotted and spare, they seem to be dissolving and coalescing at the same time.

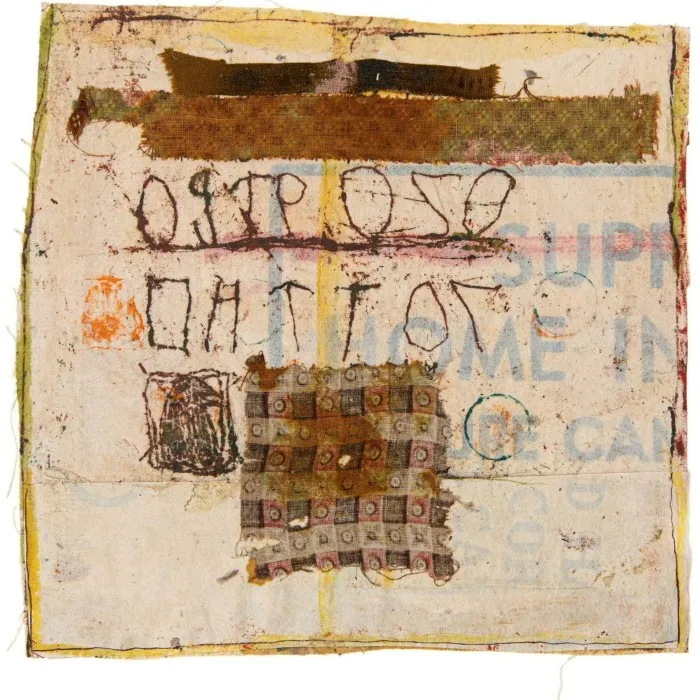

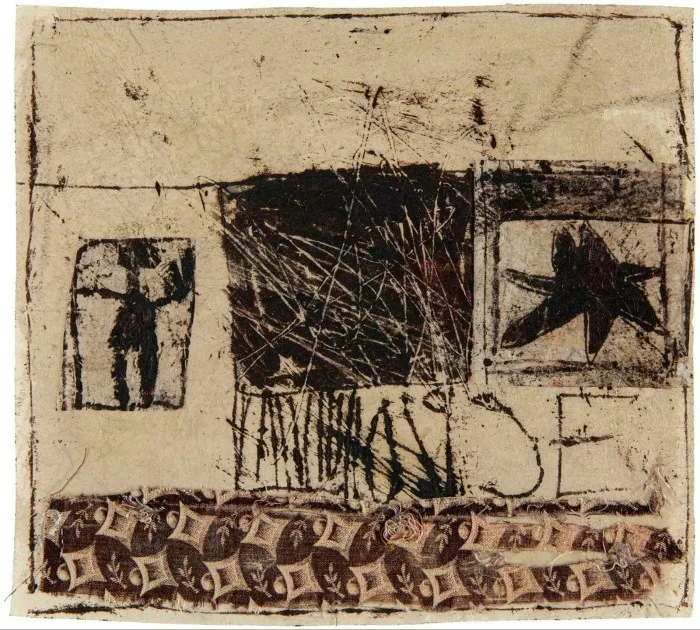

A vocabulary of cryptic motifs gels into a patchwork syntax. Stars, masks, flowers and crude figures litter the surfaces like pictographs on a cavern wall. At some point, Baron started cutting open-mouthed heads, birds and limbs out of thin sheets of copper, then inking them and gluing the resulting prints to the surface. She overlaid that vivid yet private code with indecipherable scribbles and scrawls, urgent messages to imaginary recipients.

The illegible writing, she once said, “represents all the words that have been written to tell the unimaginable and explain the unexplainable”. The runes operate less as a communicative language than as a veil, or what Baron called “an art of concealment and protection”.

She was fragile and self-taught, but not a total shut-in or a naïf. She ventured beyond the Bronx to New York’s museums and occasionally even dipped a toe in the city’s intoxicating art scene. Her husband, Herman, was a book salesman and his brother, Oscar, ran a small press that published avant-garde writers such as Maya Deren and William Carlos Williams.

The collages reflect a familiarity with prehistoric cave art, Native American petroglyphs, Surrealism, Paul Klee and Baron’s local contemporary, Robert Rauschenberg. She was surely well versed in the Dada assemblages of Kurt Schwitters.

Certain boxlike sculptures, cobbled together from weathered driftwood, junk and wire, call to mind the epic concoctions Louise Nevelson made from her neighbourhood’s refuse — only in miniature. Like Nevelson, Baron disguised the origins of her bits and bobs. Part fetish, part reliquary, each work advertises its maker’s reticence and her need to share. Those competing opposites produce a magnetic hum.

It’s tempting to lump her meticulous kitchen-table constructions together with the boxes that Joseph Cornell built around the same time in Queens. But they are quite different: Cornell juices his fabrications with doses of whimsy and nostalgia. Baron’s pieces, on the other hand, teeter on the edge of nihilism. They are fragments shored against the ruins of her past life.

Rauschenberg’s influence is more direct. He too scoured the streets for evocative trash to haul back to his studio and splatter with paint. Baron must have felt an affinity with this artist who balanced a rebellious desire to spin public statements out of rubbish with a countervailing need to hide his sexuality. Perhaps she even saw the “Scatole Personali” (personal boxes) that Rauschenberg built while travelling in Italy and north Africa with his lover Cy Twombly in 1952-53, each a mini-closet of sorts, filled with bones, thorns and other talismans.

Baron’s collages, like Rauschenberg’s canvases, start out already freighted with experience. They are the shade of her aged skin, a surface on which she applies the scars of memory. “The reason I use old cloth,” she explained, “is that the new materials lack the sentiment of the old.” The art she made merged fossil and palimpsest, fixing the past and also disguising it in non-sequiturs, bits of imagery and sprays of gibberish.

In a way, her intensely private approach echoed the public rhythms of the city she adopted as her own. New York is constantly bricking over its past and, at the same time, baring forgotten scraps of itself, as when a demolition exposes a faded advertisement that was painted on the side of the building and then covered for decades. Her collages — and this show — remind us that not everything we mourn is truly gone.

To March 23, michaelrosenfeldart.com