When the Guggenheim introduced Hilma af Klint to New York in a blazing 2018-19 retrospective, it scooped sublime canvases out of obscurity and laid them out like freshly polished gems. They were big, abstract and geometrical, yet they also celebrated recognisable organic forms. Molluscs, eggs, snails, roses, seed pods and marrows populated a pastel universe. Luminous golds and blues, fields of lavender and orange, wheels, grids and coiled springs all came together in a giddy ballet.

MoMA’s follow-up to that mystical blockbuster, What Stands Behind the Flowers, is a different affair, full of quiet delights, puzzling codes and a background hum of spiritual intensity that may resonate more with others than it does with me. In 1917, having completed those monumental canvases, af Klint started tramping purposefully through the countryside near Stockholm. She returned to her studio with a series of 46 portraits of flowers that MoMA acquired in 2022.

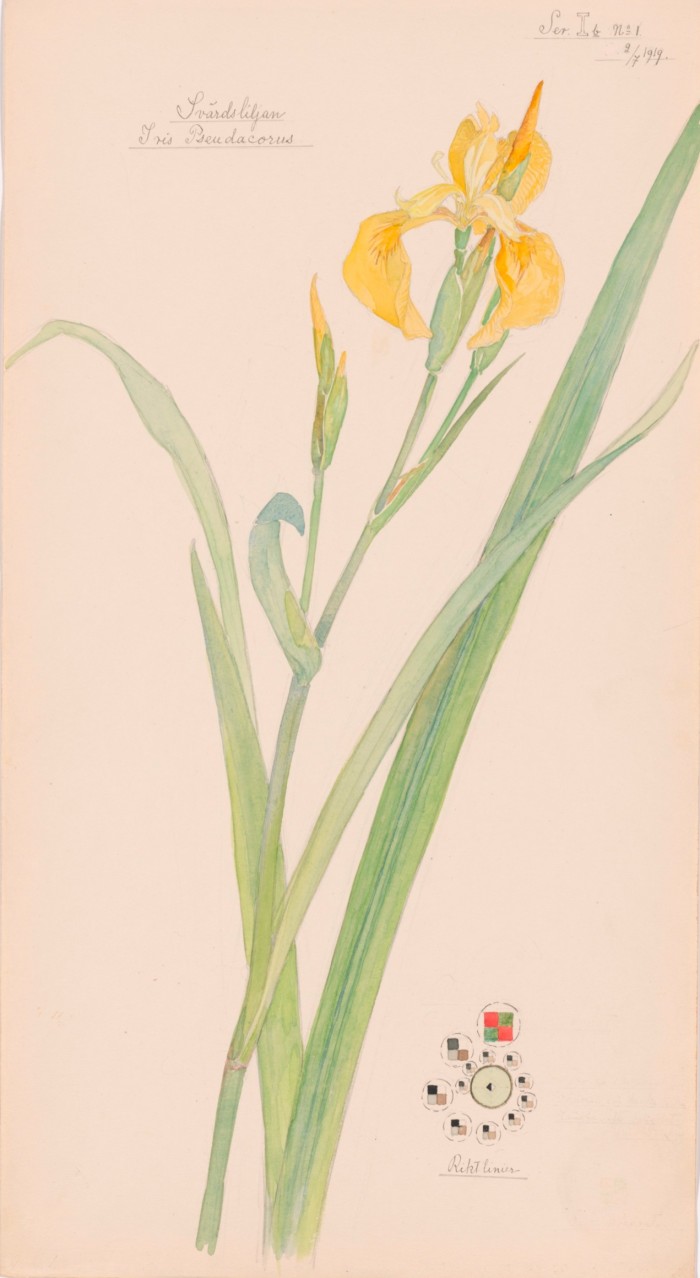

What makes them more than just sensitively detailed botanical drawings are the tiny geometric symbols that accompany each stem. Squares, grids, circles and lines of force mark each drawing, like the flight path of a minuscule spaceship or a mathematically precise fruit fly.

A yellow iris speeds upward, its rocket-like bud shooting from a V of long leaves that careen off the edge of the page. You can feel the power coursing through the xylem. In the lower right-hand corner of the sheet, af Klint adds an enigmatic gloss, tiny arrangements of squares inside bubbles that move in a tight spiral around another circle. It could be a diagram of planetary or atomic movement, but the feeling is static. The eye flits confusedly between the bloom’s sensual, impersonal beauty and the incongruous cryptogram.

These glyphs must mean something, or did to af Klint, but not even the combined efforts of MoMA’s curator Jodi Hauptman and botanist Lena Struwe could unlock their secret significance. “What is the relationship between floral abundance so lush in colour, so precise in detail that we can practically smell its wafting scents and feel its prickly, sticky, or downy foliage, and geometries that are almost (but not quite) familiar from scientific textbooks, maps, and charts?” Hauptman asks in a catalogue essay.

The answer is unsatisfying. There is no key, or even a consistent relationship between a flower’s inherent organic qualities and the geometries af Klint applies. And so we can only accept the juxtapositions and bask in their visual discord. Treat these drawings as a code to be cracked and you’ll leave the galleries in frustration; savour the randomness and you come closer to the confounding expressiveness of a deeply original artist. Unfortunately, I’m not always able to reconcile her combination of universal grandeur and personal quirk.

Af Klint was convinced that the world was not ready for her art. She decreed that her work must not be publicly exhibited for 20 years after her death, and so, in 1944, more than 1,200 items proceeded directly to storage. By the 1980s enough of them had emerged to secure her a cult following, which grew to general rejoicing with her Guggenheim debut.

MoMA picks up her story after the first world war, when af Klint declared herself tired of being “lectured to” by the spirit guides that informed her massive, ecstatic canvases. She felt ready to “fill the bowl” with her own “self-studies”, by which she meant looking for her reflection in the mirror of nature.

“When we turn our gaze towards the plant kingdom,” she wrote, “it gives us information about the composition of our own being.”

Af Klint was a scientific illustrator, a profession that overlapped with her life-long passion for plants. She launched her floral series in April 1919 with an early portent of rebirth: Anemone hepatica. In the drawing, brown and green tendrils struggle out of ripening mud and into warm sunlight. Floating above that thicket like a heavenly apparition is a solitary, perfect flower in full spring regalia of sepals, stigma and stamens.

Just to the right of that aerial bud, a pair of interlocked triangles pointing in opposite directions forms a six-pointed star with a heavenly wheel at its centre. Af Klint wrote in a notebook that the hepatica “possesses a radiant hope” and she initially labelled the diagram with the word “joy”. Then she erased the annotation, leaving the image to communicate that rapture of possibility alone.

“The artist’s radical move here was to link the plant and spirit — something observed and something envisioned — and despite their seeming dissonance make them work together,” Hauptman writes. Other artists had asked nature to speak the language of the soul — think of Caspar David Friedrich’s irradiated mountains or Edvard Munch’s whispering shores. But af Klint cleaved the material from the spiritual, setting evidence and mystery side by side.

As she continued to forage through two growing seasons near her studio on the island of Munsö, she expanded her botanical inventory and her vocabulary of signs. Weeds especially appealed to her, perhaps because she saw in them fragments of divine splendour that others overlooked.

Sometimes the diagrams reflect inherent properties of the flower. Pinesap (Monotropa hypopitys), for instance, needs no natural light (since it does not produce chlorophyll), and af Klint emblazoned her drawing of it with an aptly dark orb, bristling with spikes of purple and gold. Mostly, though, it’s hard to know what insight she is teasing.

The combination of implied revelation and deliberate obscurity can be frustrating, but the gently impassive style of the drawings suggests that she had higher aspirations than making life easy for the viewer. Her eye was on the valley floor, but her head was in the clouds.

To September 27, moma.org